What killed orca J34?

Cause of blunt force trauma still unclear in endangered killer whales

Annual status updates (in remembrance):

- 20 Dec 2020: Final necropsy report not yet released

- 20 Dec 2019: Final necropsy report not yet released

- 20 Dec 2018: Final necropsy report not yet released

- 20 Dec 2017: Final necropsy report not yet released

- 20 Dec 2016: Sechelt Band members spot J34 floating dead off the Trail Islands (B.C., Canada)

2020 call to action:

Ask DFO to release the final necropsy report so we can all learn as much as possible about how to prevent death by blunt force trauma in endangered southern resident killer whales like J34.

Specific unanswered questions:

- Given the proximity of the Nanoose Range, in what ways was acoustic trauma assessed, and what was the condition of J34’s auditory system?

- Does the nature of the blunt force trauma suggest the mechanism of injury was a vessel, and if so what type of boat or ship operating in what way(s)?

- If the investigation assessed any video of a potential strike of a killer whale in the days immediately prior to J34’s stranding, what were the results?

Two years ago today, on Tuesday 20 Dec 2016, the dead body of a southern resident killer whale (SRKW) known as J34 was discovered floating in the Strait of Georgia just north of Vancouver (BC, Canada). Also known as Double Stuf, J34 was a beloved adult (18 y.o.) male member of J pod who suffered “blunt force trauma” from a still unknown or unspecified source. We should ask every year, on December 20: what killed J34 and how we can prevent such tragic losses from happening again?

This post serves as a place to aggregate what we know about the stranding of J34. It is revised whenever new information surfaces from the investigation of his death, and as we learn generally about the nature and causes of blunt force trauma in cetaceans. The post is organized into three sections: evidence; discussion; and conclusions.

Please add your contributions in the comments. We’ll intermittently incorporate new information and ideas into this post. Citizen scientists are welcome to process, re-analyze, or contribute to the J34 stranding raw data archive. We also maintain a similar on-going blog post regarding the stranding of SRKW L112 in February, 2012, which may provide valuable comparisons to the case of J34.

Here at Beam Reach we are especially motivated to learn as much as we can from J34’s death because as a younger whale (in 2007), he and his immediate family gave us bioacousticians a very rare opportunity to spatially document communication of SRKWs by using an array of hydrophones to localize each call. While J34 and his mother, J22, traveled along the west side of San Juan Island, his four-year-old brother J38 (a particularly curious juvenile?) strayed away and made a rare, close approach to an array of hydrophones we were towing behind our hybrid-electric research catamaran.

In the animation, you can listen to these family members calling back and forth as you watch the moving dots which indicate the relative locations of J38 and J34/J22. We don’t know if the responses to J38 came from his mother or his sibling (because the stay closer together than the precision of our localizations), but on dark days like December 20 it’s heart-warming to think of J34 as an attentive and talkative older brother.

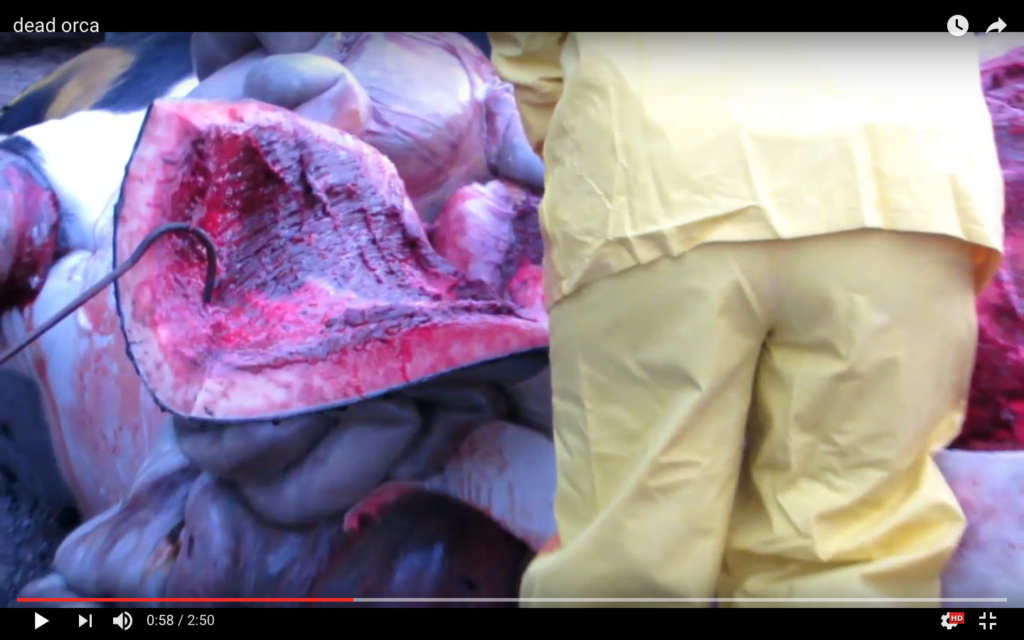

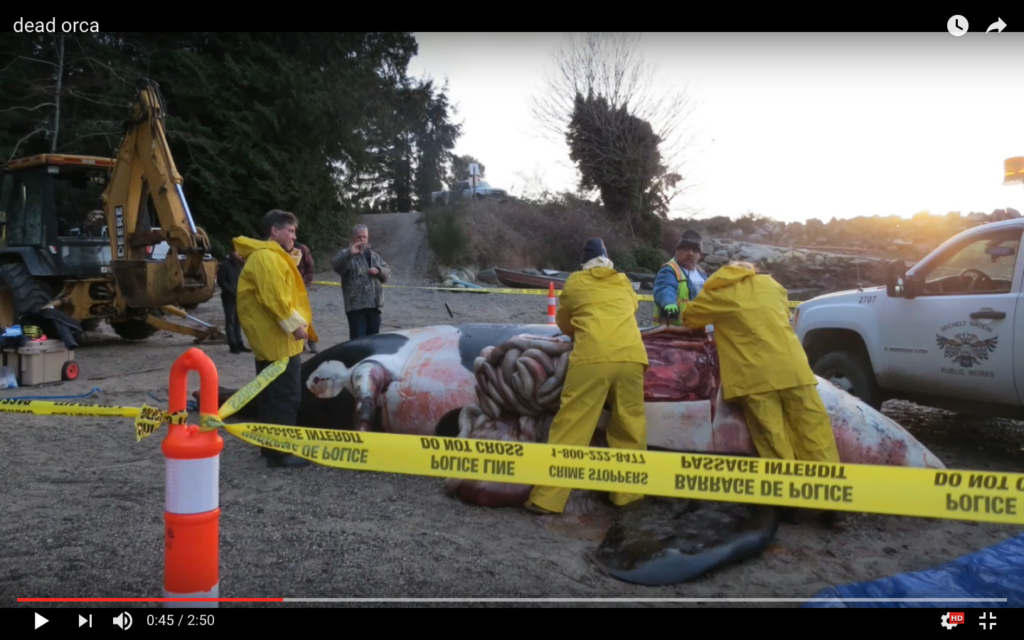

WARNING: Graphic material!

This remainder of the blog post contains photographs and videos of dead orcas and the necropsy of killer whales, including J34. A necropsy, also known as an autopsy, is a postmortem examination that often includes anatomical dissection. Please don’t read on if you would rather not view these media which can be upsetting, but contain essential information for understanding what mechanisms injure and/or kill wildlife that we all value and want to conserve.

The results of J34’s necropsy will feed into a growing body of knowledge to assist in assessing the threats to Southern Resident killer whales…

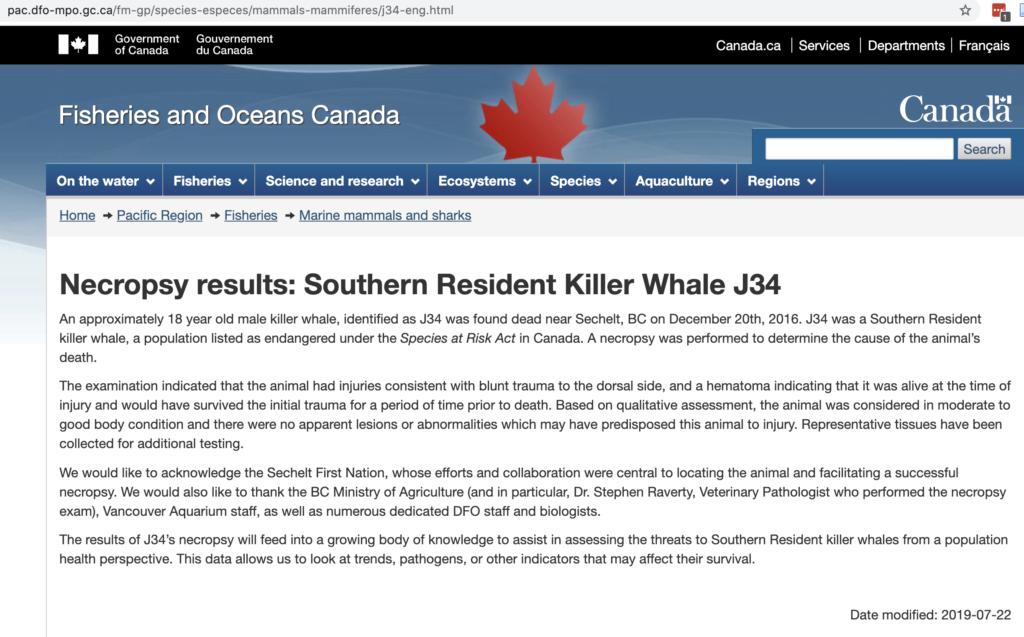

Initial Necropsy Results SRKW J34, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Still no details… Where is the actual report?

This 4-paragraph notice stands in stark contrast to the report that NOAA has provided for L-112… or the synopsis of L112’s case provided by the SeaDoc Society and the summary of the gross necropsy by Cascadia Research.

Evidence:

The following sections present the various lines of evidence that are pertinent to understanding the stranding and injuries of J34. To understand each line, it may be helpful to refer to the J34 stranding map and/or the J34 stranding chronology.

Pre- and post-stranding distributions of SRKWs and other marine life

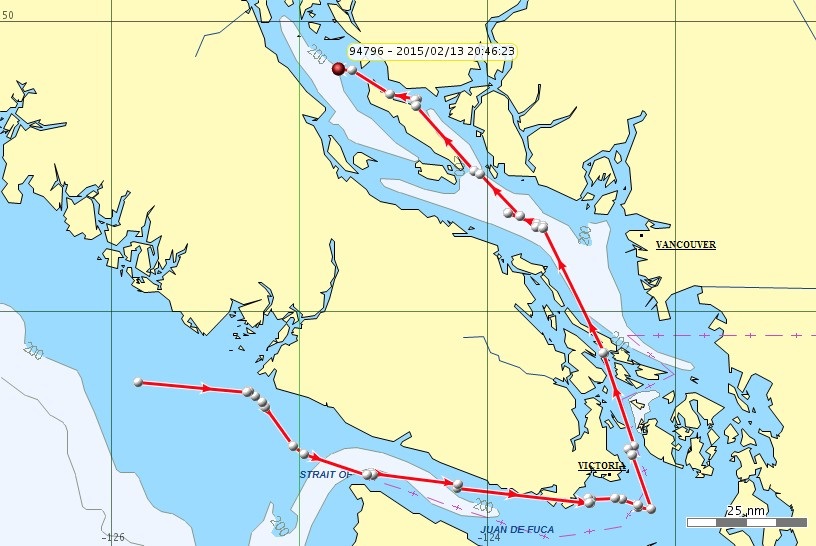

Historic distribution from NOAA satellite tags

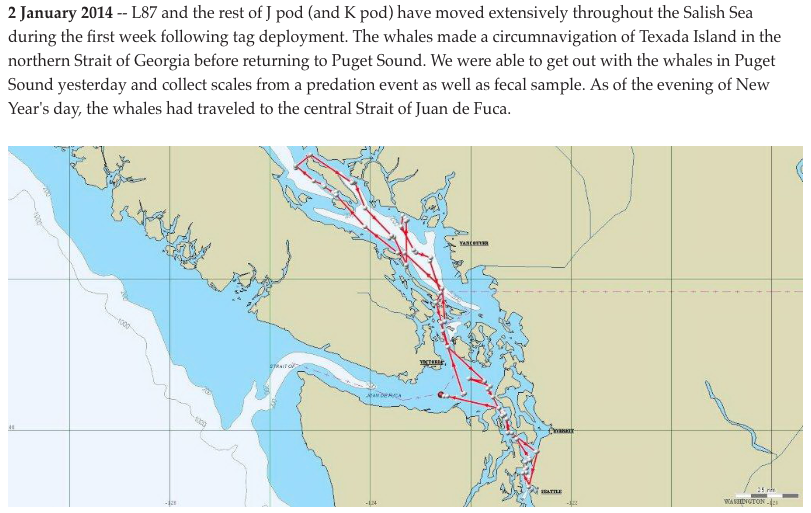

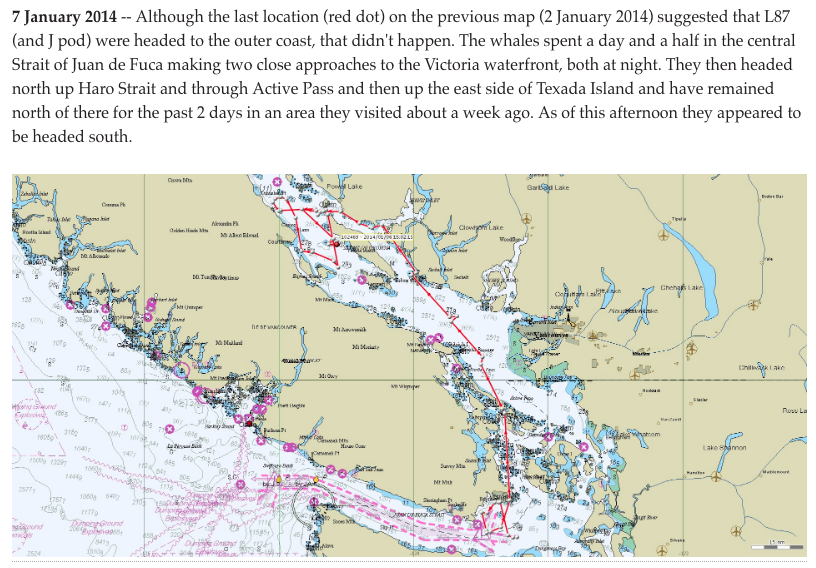

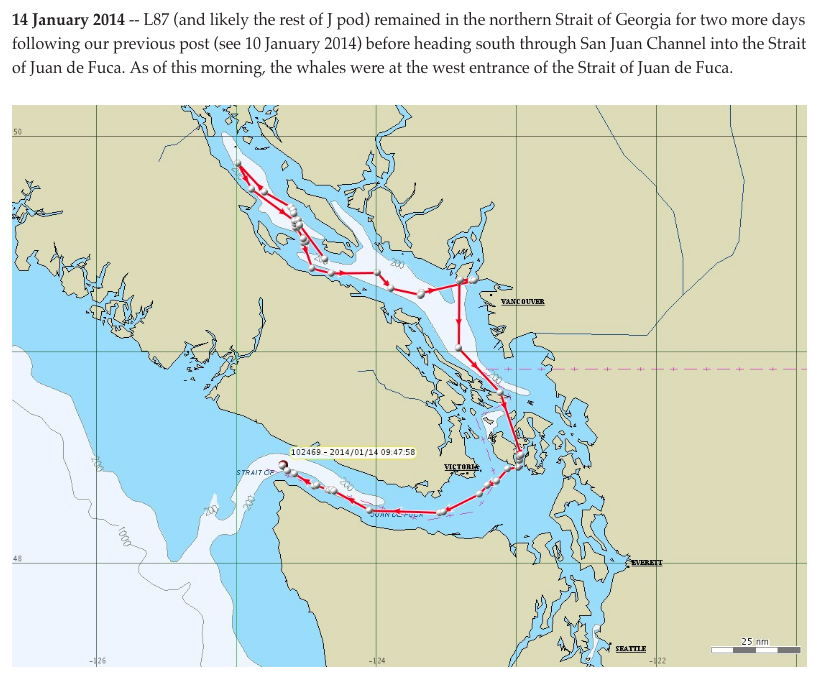

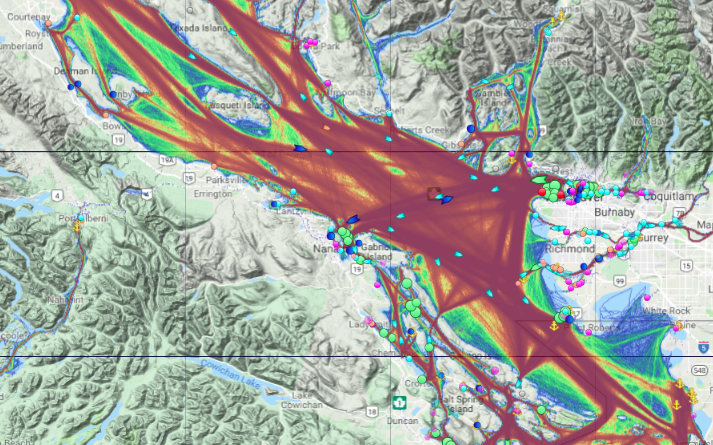

If you look at the maps of critical habitat for SRKWs in the U.S. and Canada, you might easily conclude that SRKWs rarely if ever travel north of the Fraser River delta. However, these maps — even if corrected for effort — are heavily biased to the summertime distribution.

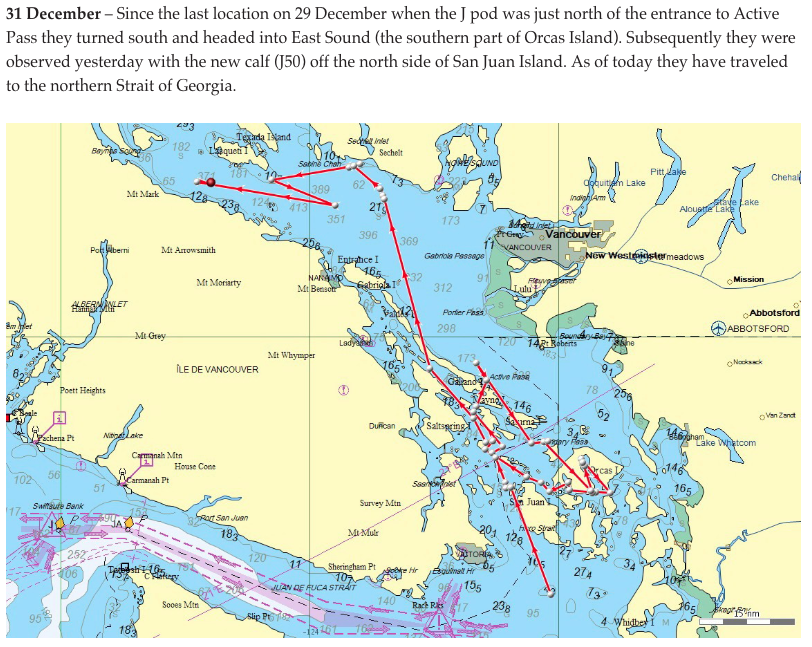

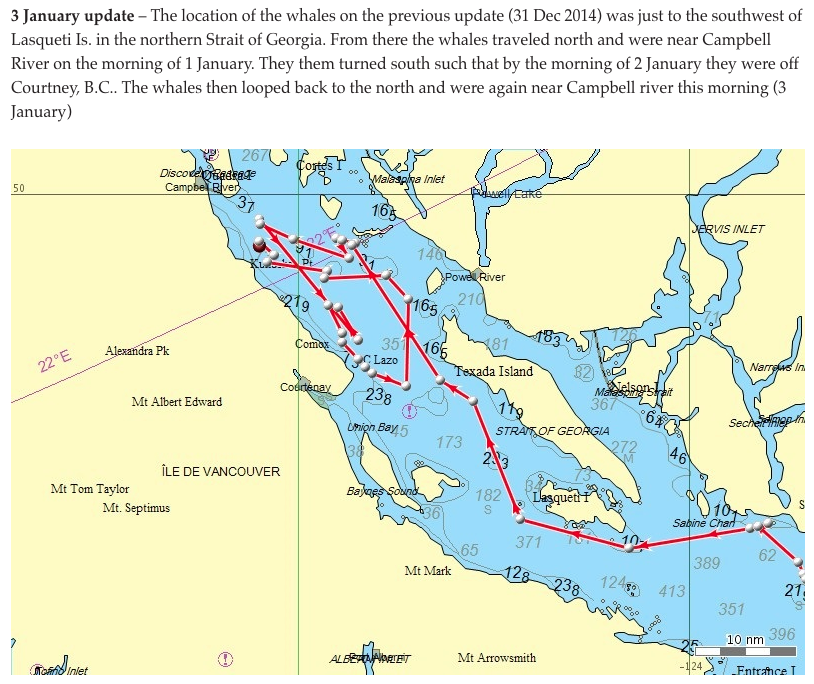

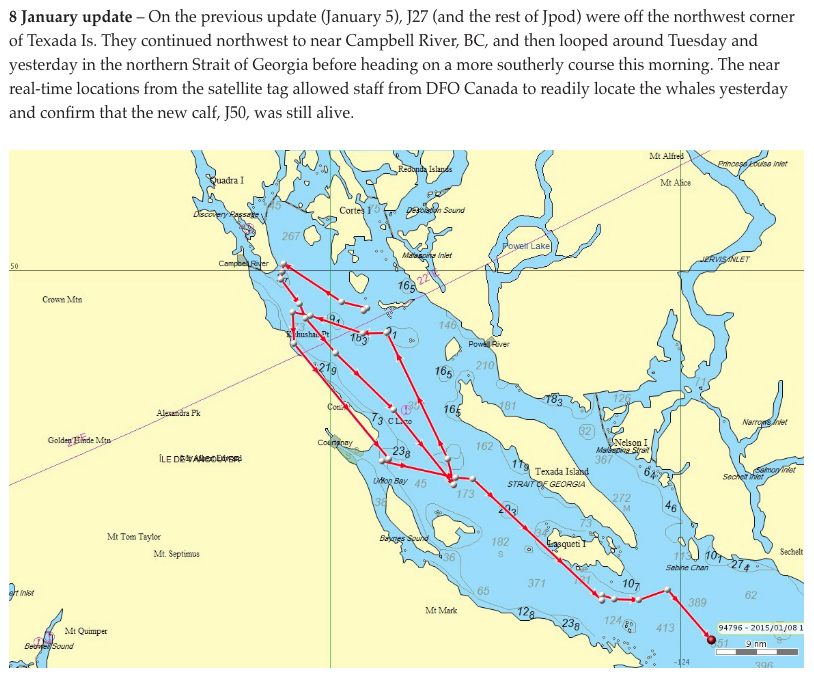

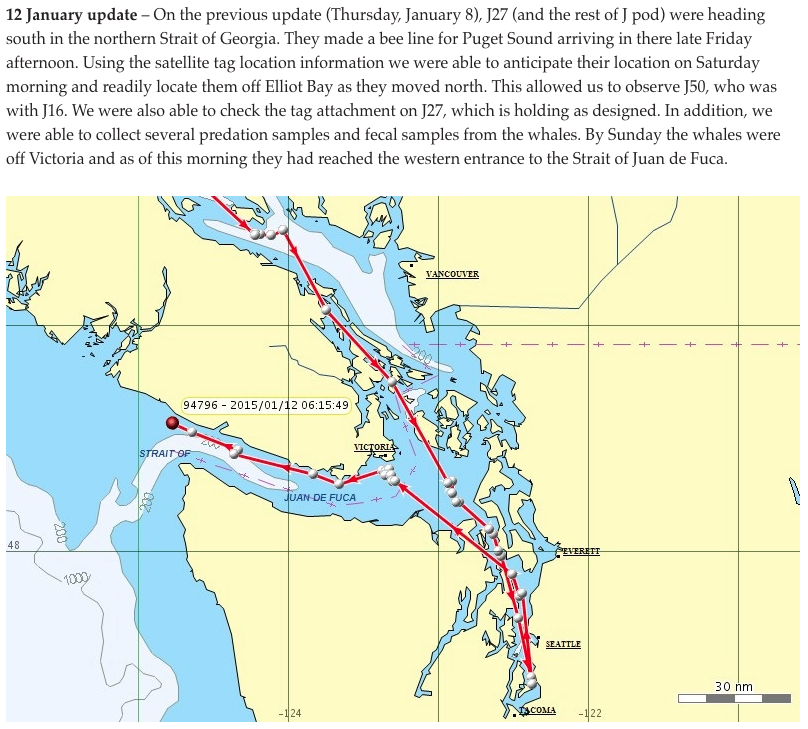

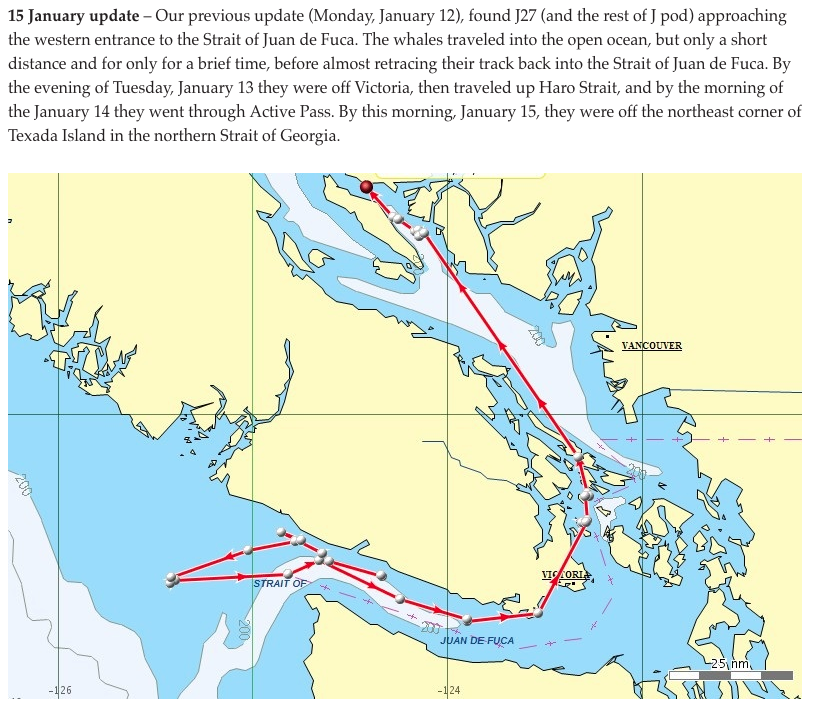

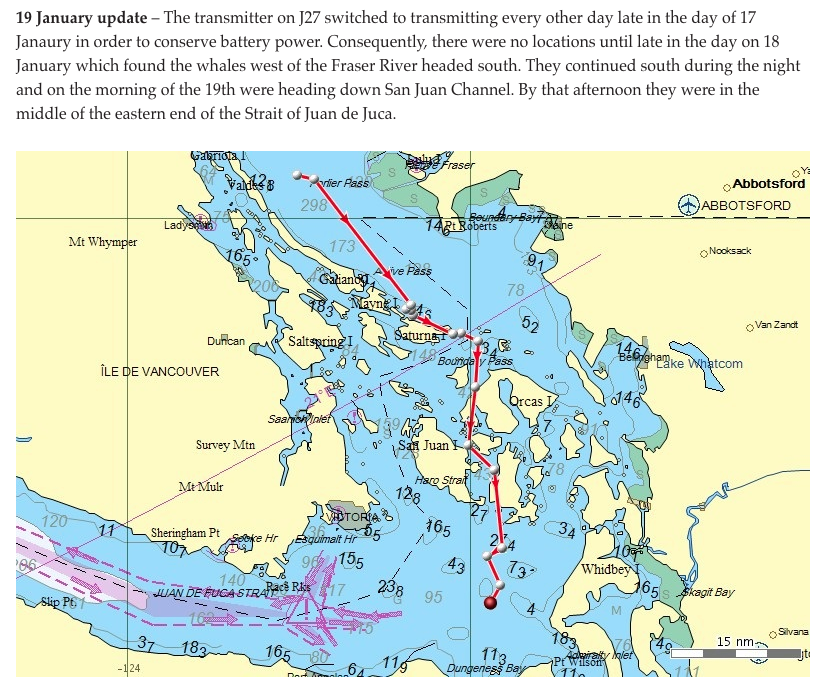

One important insight from the NOAA-led satellite tagging program is that during the winter months (Dec-Feb) the entire Strait of Georgia is was traversed by SRKWs. Based on tags deployed during the winters of 2014 and 2015, J pod commonly circumnavigates Texada Island (based on tagged individuals L87 who travels with J pod and J27). The typical route taken by J pod to or from the northern Strait of Georgia is via the Active Pass and in the main basin (between the Gulf Islands and the Vancouver mainland). Interestingly, during the winter the Fraser delta does not seem to be a point of interest as it is during the summertime.

Pre-stranding distributions

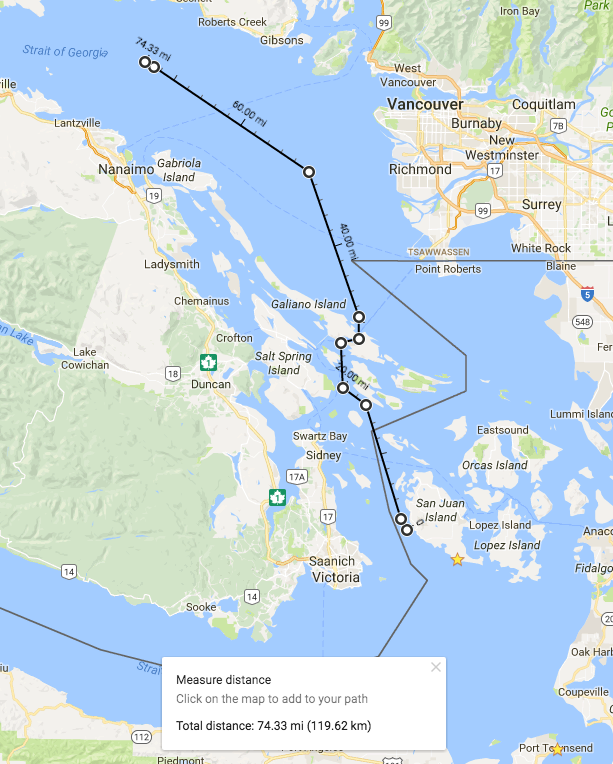

The J34 stranding map shows the last sighting of J34 (in Puget Sound) on 12/14/16. It also depicts the progression of acoustic detections of J pod from Haro Strait (at 3 am on 12/17) to the Fraser river delta (~9 hours later, just after noon on 12/17). The map below suggests that if J pod took their typical route via Active Pass, the distance traveled in those 9 hours is about 50 km, suggesting their speed was 5 kph (a typical mean speed for SRKWs). If they had continued into the Strait of Georgia at that pace, they could have reached the vicinity of the stranding (another 70 km along the estimated track below) in about 14 hours, hypothetically arriving around 4 a.m. on Sunday 12/18/16.

The U.S. sighting networks observed and identified many of the J pod whales that J34 was with when in Puget Sound and in San Juan County on the Dec 10th and the 14th. On 12/14/2016 ~14:00:00, Orca Network reported J pod at Point Robinson (see photo below). The pod went as far south as Point Dalco and turned back east and then north at 16:35.

Distributions simultaneous to the stranding?

Are there any sightings or hearings of SRKWs and/or other marine mammals during the possible period of the stranding (roughly first 12/18-20/2016)?

Post-stranding distributions

At almost exactly the same time that J34 was located off Sechelt, J pod went south through Haro Strait (on 21 Dec ~10:00) along the west side of San Juan Island. Three days later (12/24 ~16:10) J and K calls were heard on the Lime Kiln hydrophones (lasted 2 hours).

Also on 12/24/2016, Jeanne Hyde reported hearing T018/T019 matrilines on the Orcasound Lab hydrophone (5 km north of Lime Kiln). Were any other Bigg’s KWs sighted to the north or south, before, during, or after the stranding?

Pre-stranding environmental conditions

Wind

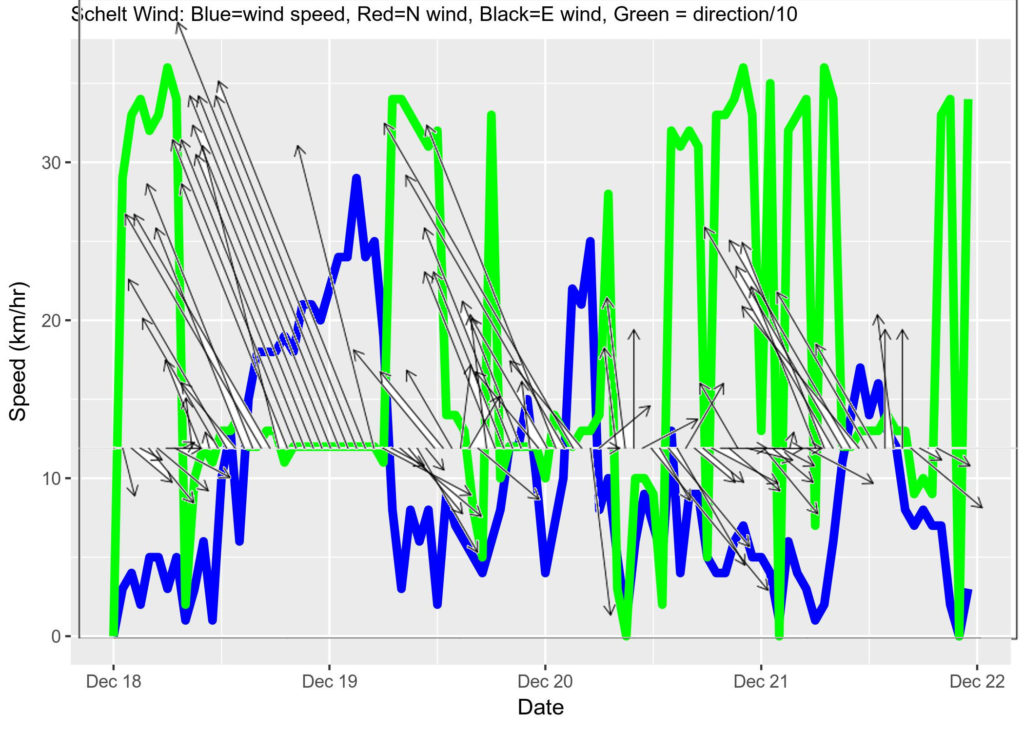

A southerly wind off Sechelet was significant (~15 kph) and rising as the body of J34 was secured and towed to shore in the late morning of 21 Dec 2016. Prior to that southerly wind event, however, the previous 24 hours experienced light northerly winds (<~5 kph). Earlier in the week — between Dec 18 and mid-morning on Dec 20 — similar light northerly winds were interrupted by 2-3 other strong southerly events. The most significant southerly storm had peak wind speeds of almost 30 kph and was sustained near 20 kph for ~18 hours, blowing consistently out of the southeast (from ~120 degrees true; towards ~300 degrees true) .

Tidal currents

We should be able to pull a surface current vector time series out of some or all of these Canadian observed data sources:

- Ocean Networks Canada ADCPs and/or other current sensors on the Venus line (nodes off the Fraser delta)

- Drifters?

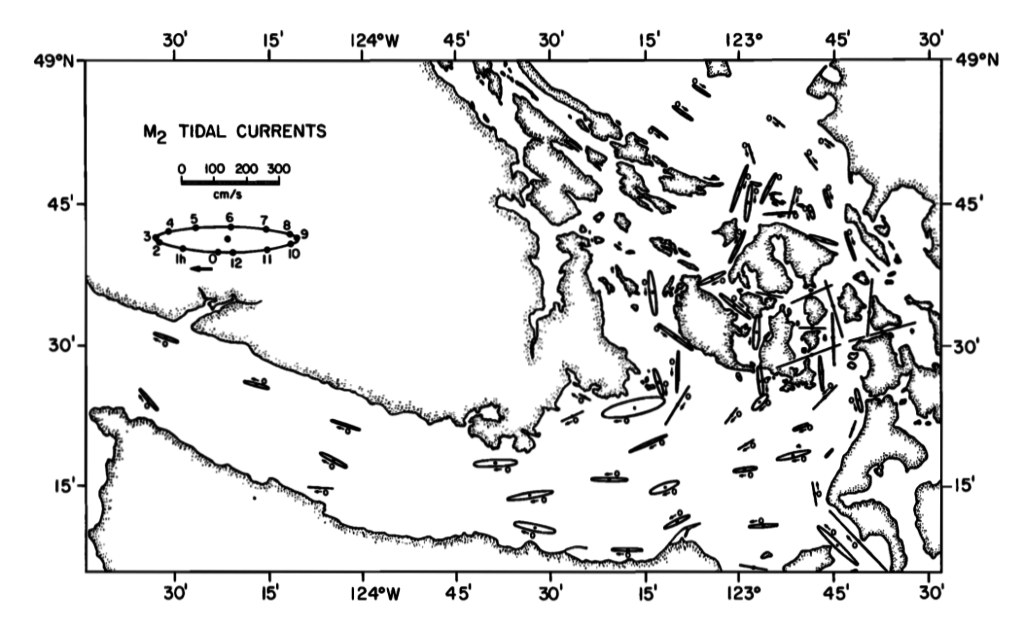

In the interim, here’s a synopsis by Mofjeld & Larsen (1984) of the dominant (M2) tidal current component depicted as current ellipses:

While a trajectory model should integrate net transport from surface currents, our current assumption (pun intended) is that the net transport was negligible and therefore the drift trajectory of J34 was governed mostly by the wind.

Tidal height

Tidal height is probably not relevant as the dominant wind direction suggests the carcass likely did not encounter the shoreline prior to being discovered. For the record, though, here is a time series from a local tidal station.

Discovery of J34 carcass

The best description of how J34 was first discovered floating dead north of Vancouver, BC, comes from an excellent synopsis written by the Sechelt First Nation [archived link | original link (broken in 2018)]. They reported that a killer whale “had been spotted floating off the Trail Islands within our territory on Tuesday evening, December 20th, 2016.” The synopsis also includes these helpful details:

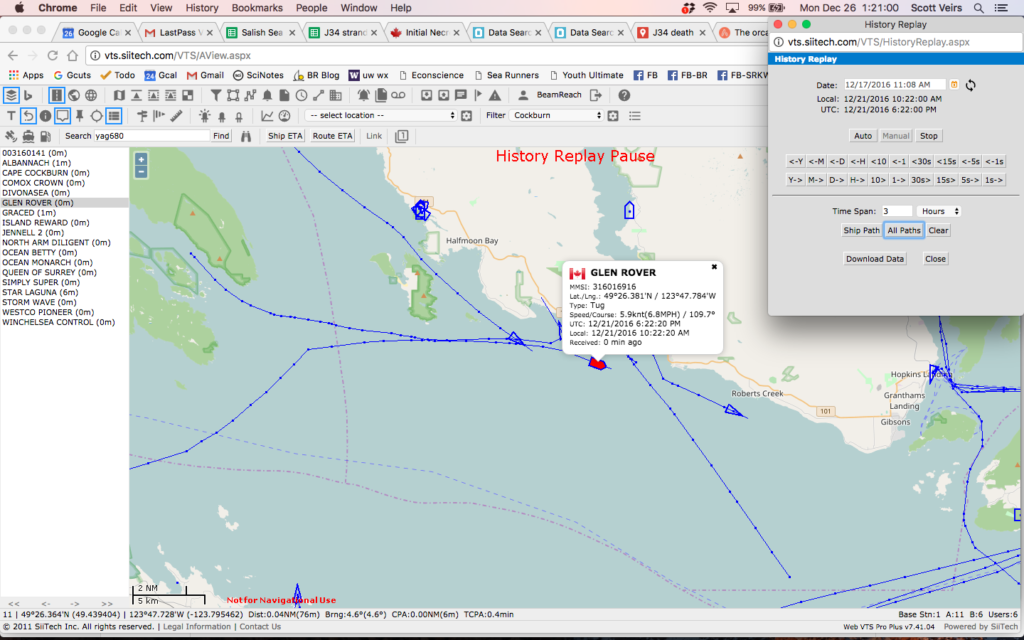

“Immediately, shÃshálh Nation member Vern Joe on his gillnet vessel “Sechelt Renegade†sprang into action to try to recover the whale however, was unable to locate the mammal in darkness. Paul Cottrell arrived at the shÃshálh Nation offices the following morning, December 21st, 2016 and travelled with Resource Management Director Sid Quinn and Fisheries Technician Dwayne Paul to search the last known location. Despite challenging sea conditions, the 26-foot aluminum crew vessel owned by the Nation was able to assist in the recovery of the whale. The whale had been spotted during our search by a passing tug at approximately 11:00AM, two nautical miles off the southern most Trail Island.”

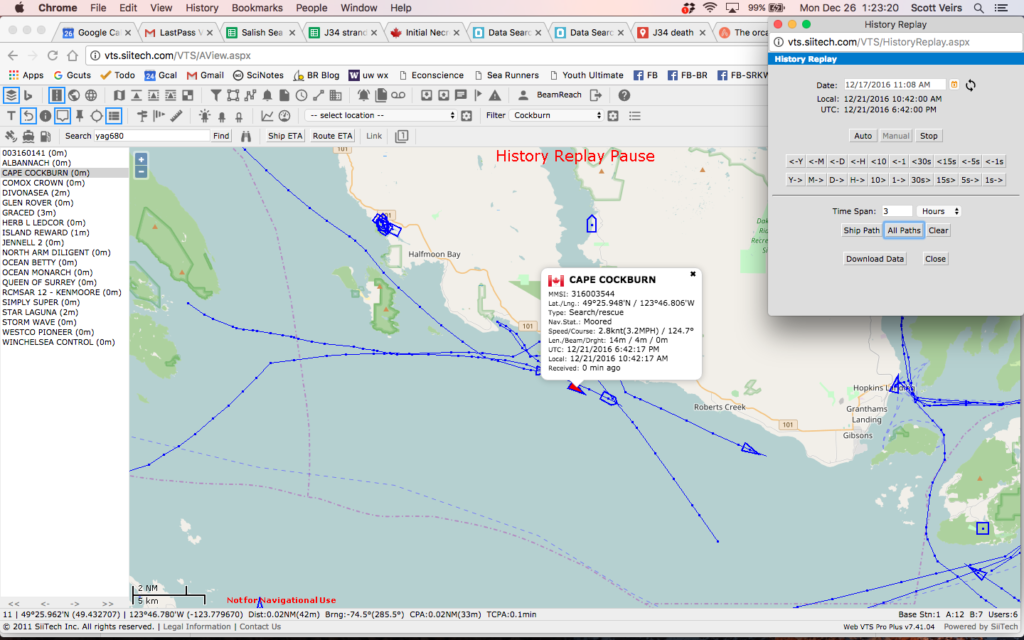

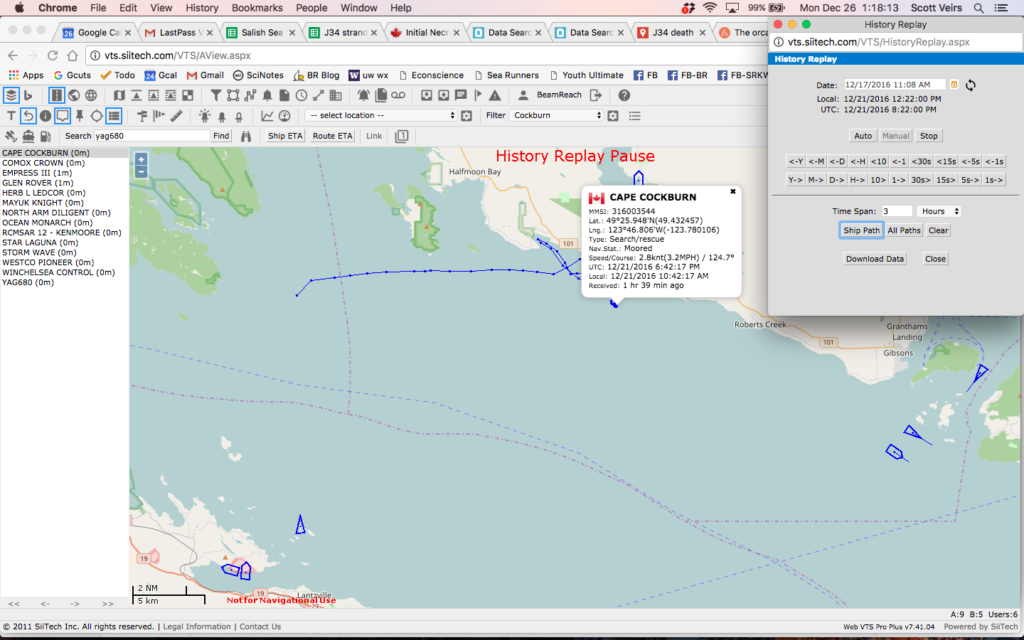

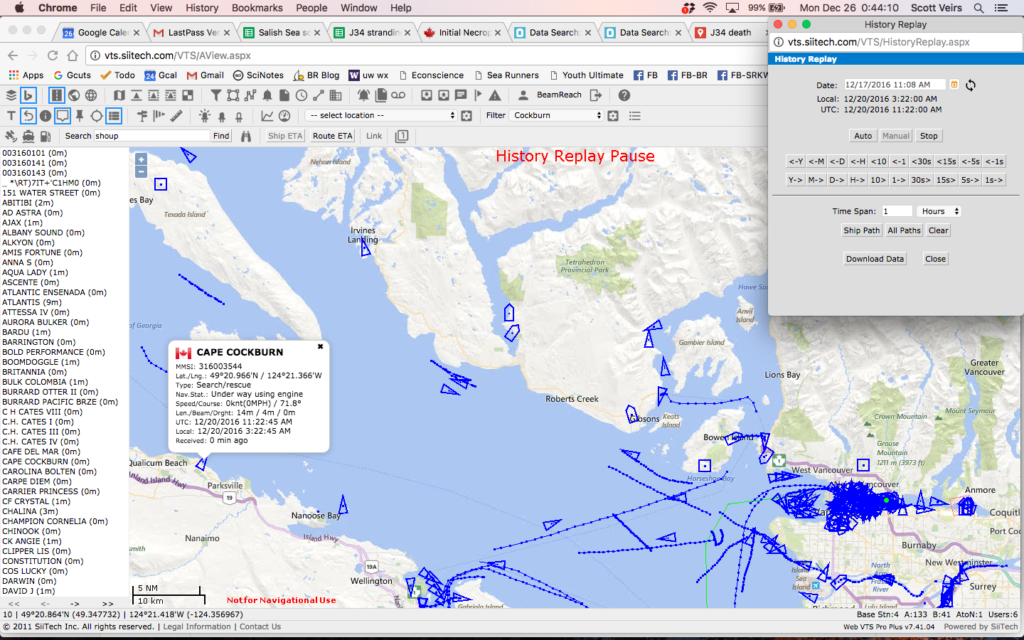

“Coast guard vessel, Cape Cockburn, towed the whale into the breakwater area located in Selma Park after it had been secured with a rope from the FOC zodiac operated by Fisheries Officers out of Powell River, BC.”

In their initial necropsy results (see below), DFO, described the discovery in a consistent, but more succinct way:

An approximately 18 year old male killer whale, identified as J34 was found dead near Sechelt, B.C. on December 20th, 2016.

Vessel traffic records

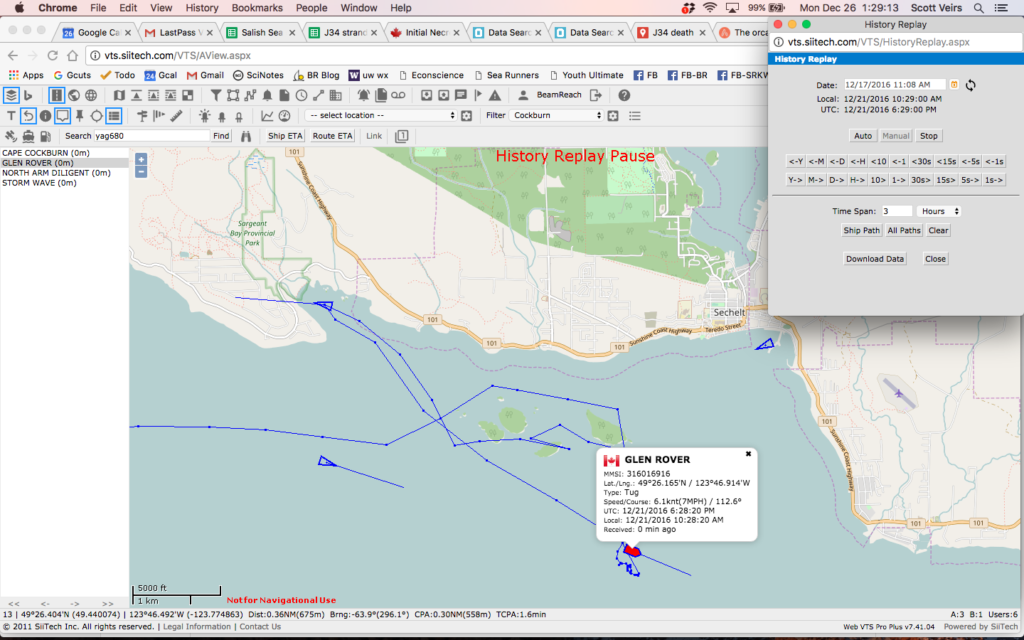

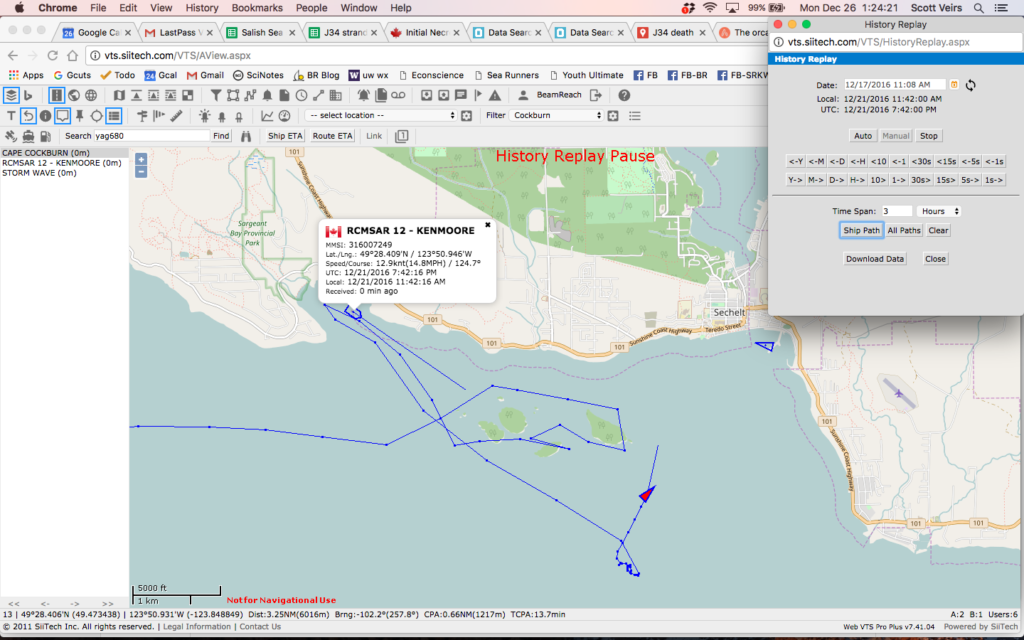

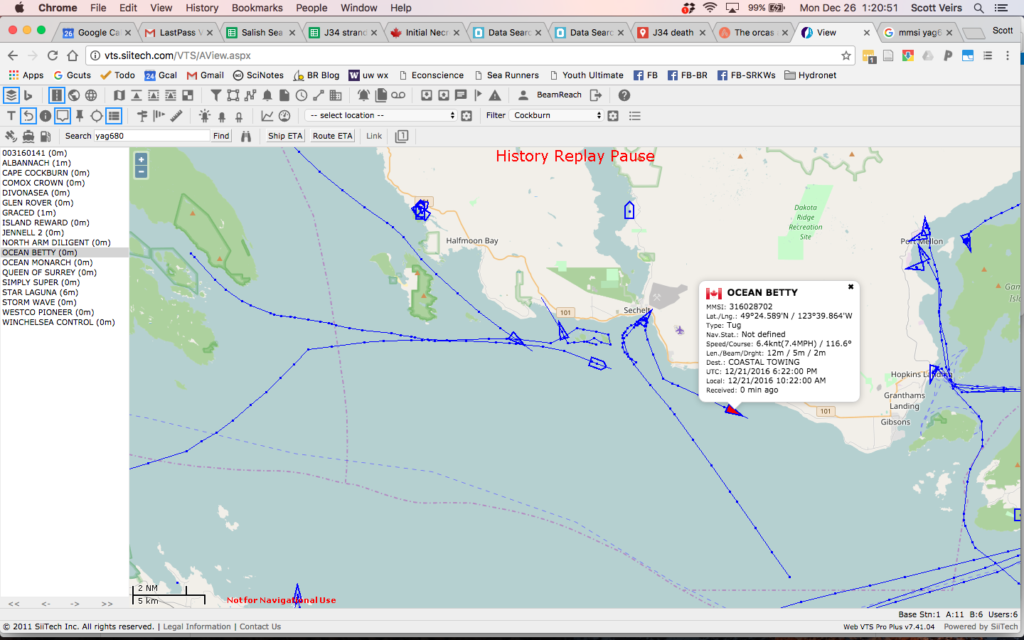

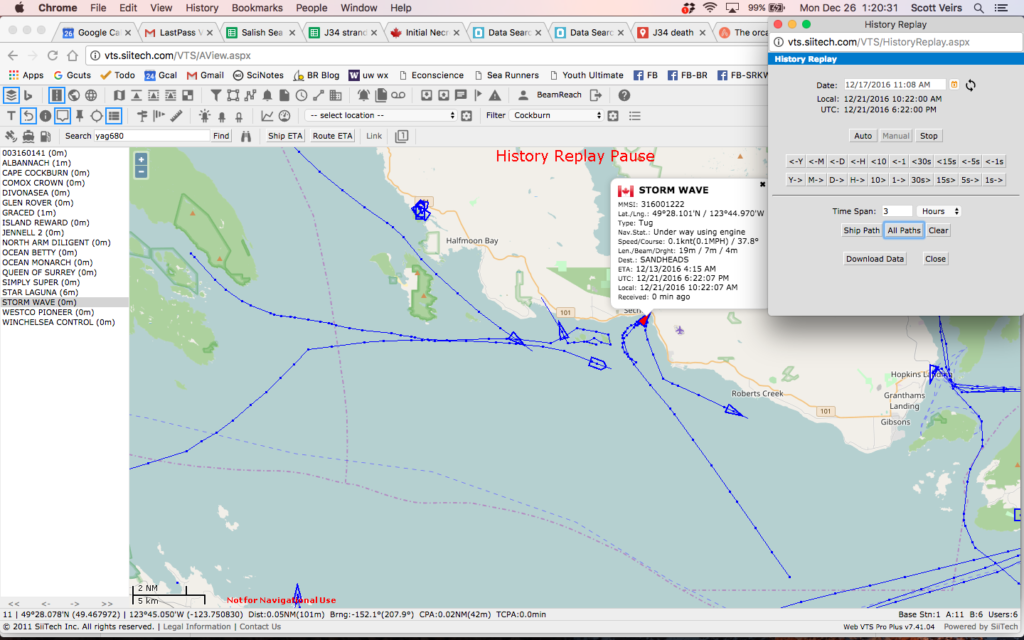

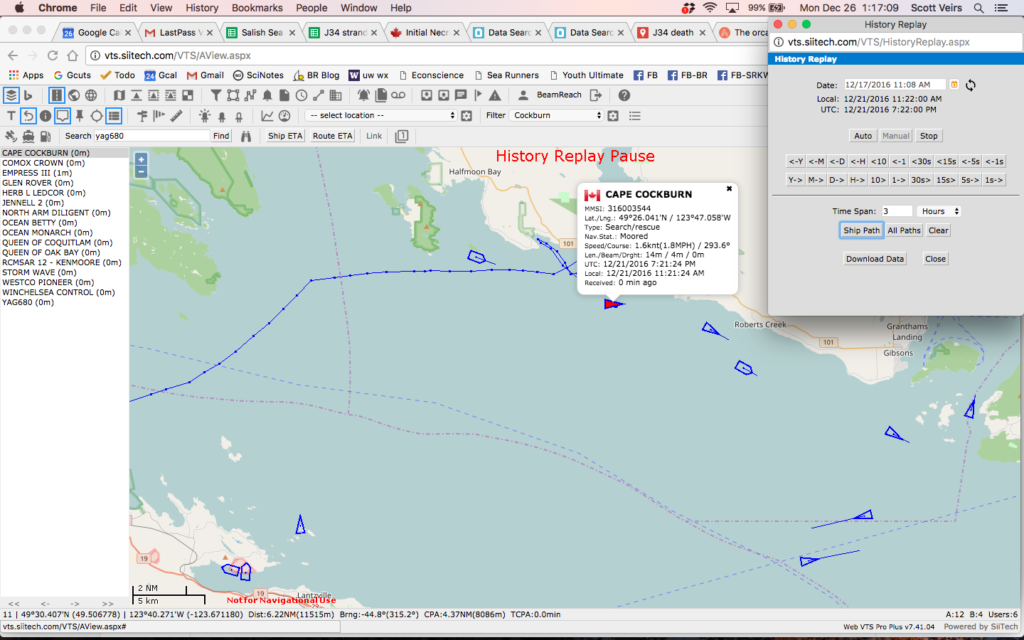

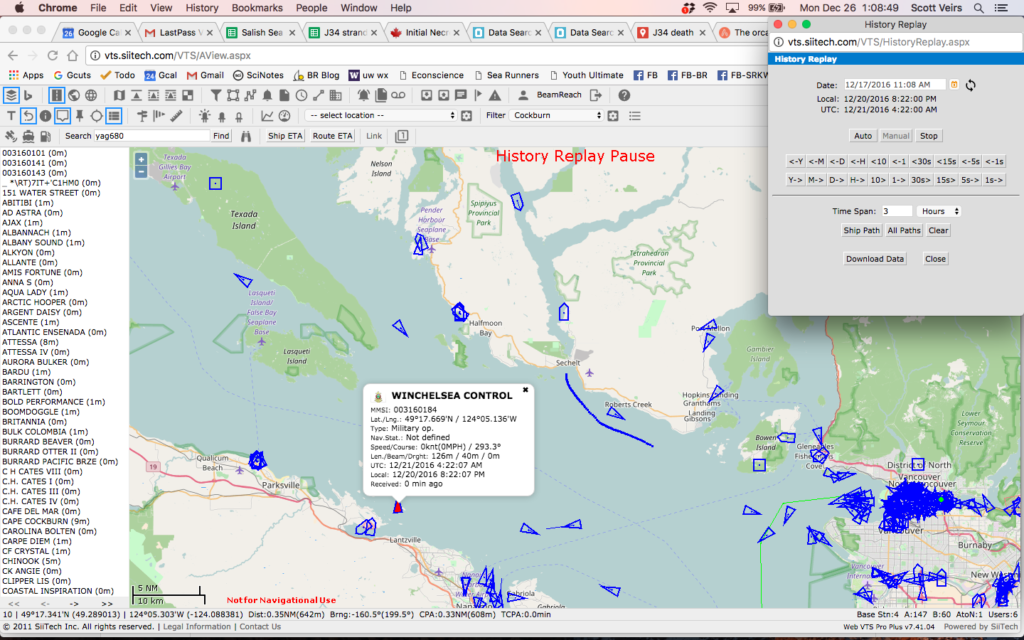

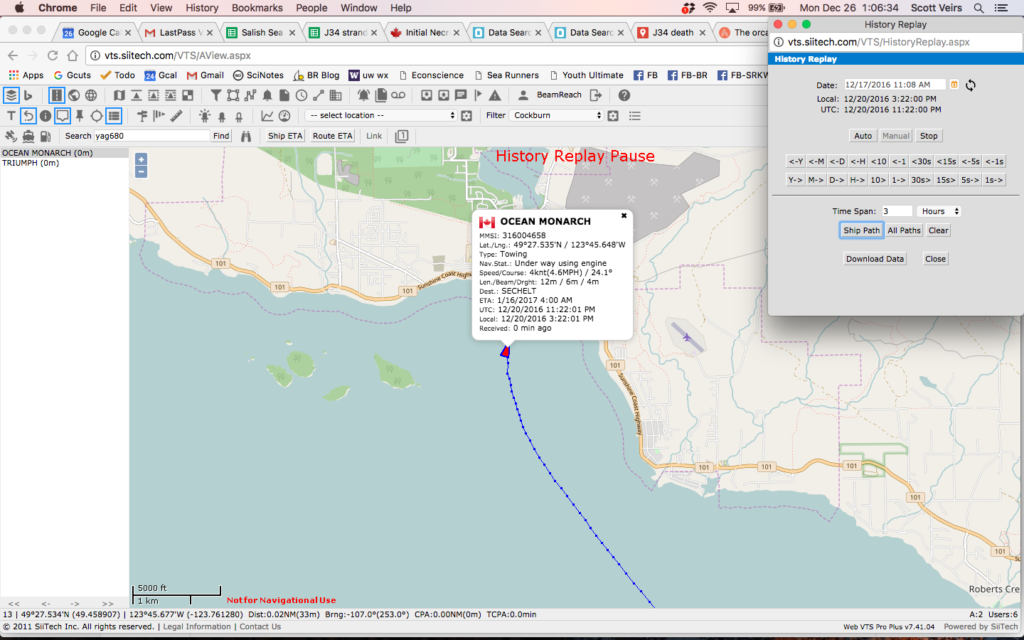

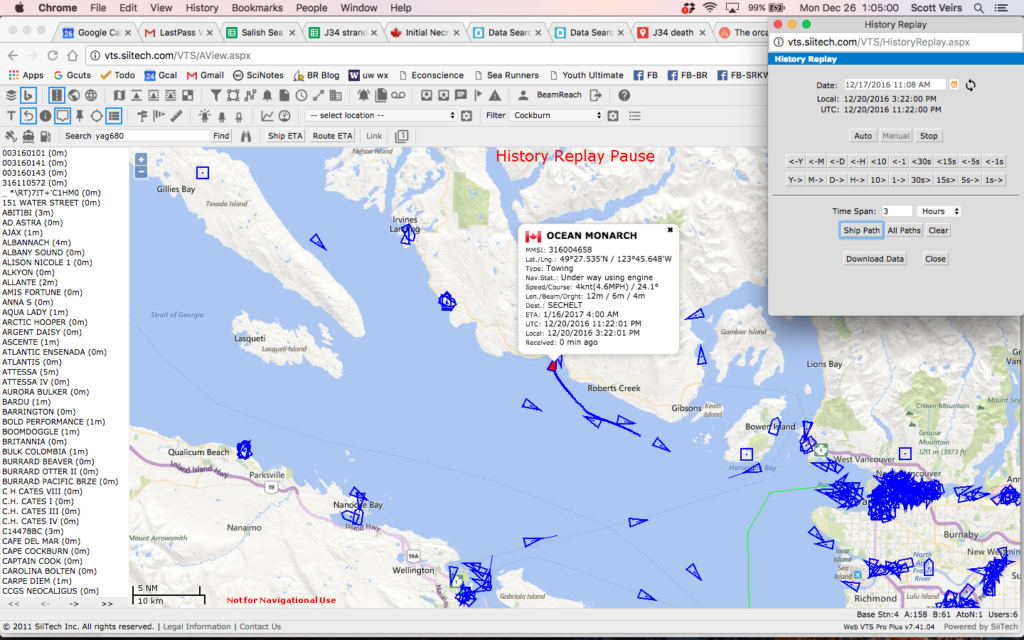

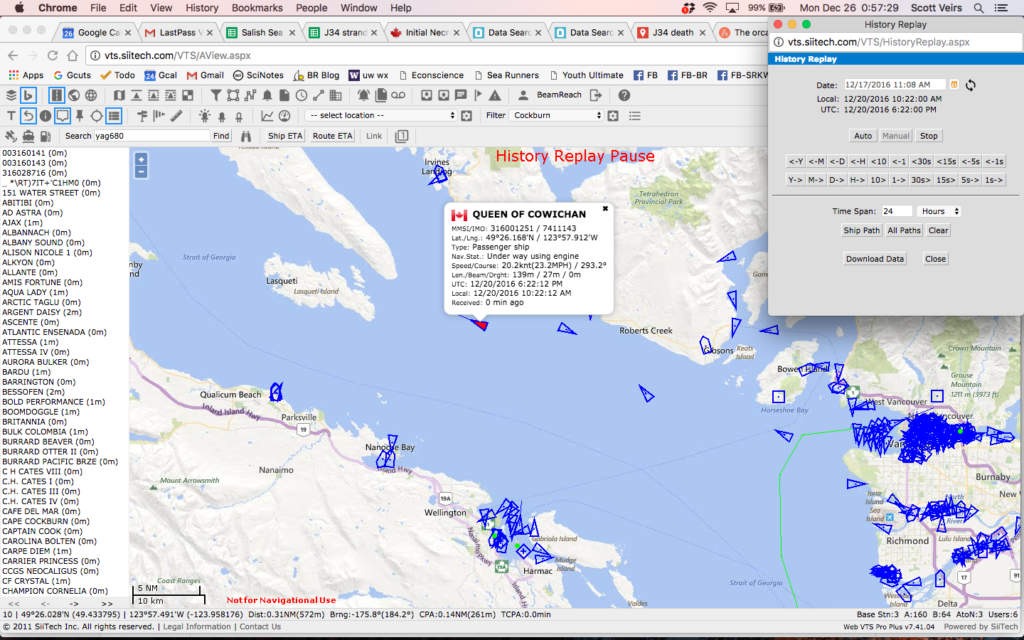

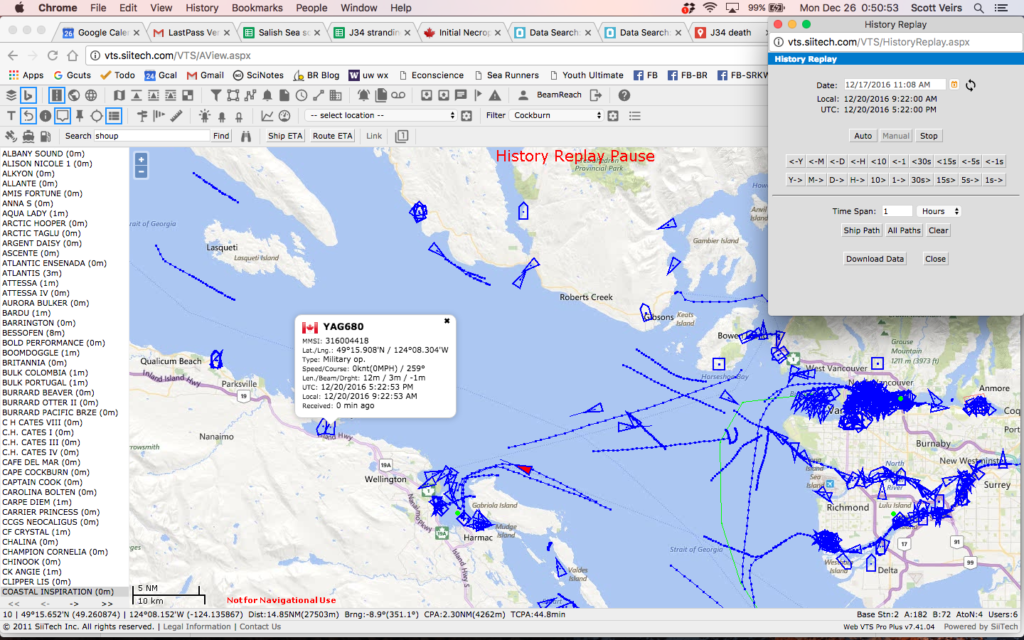

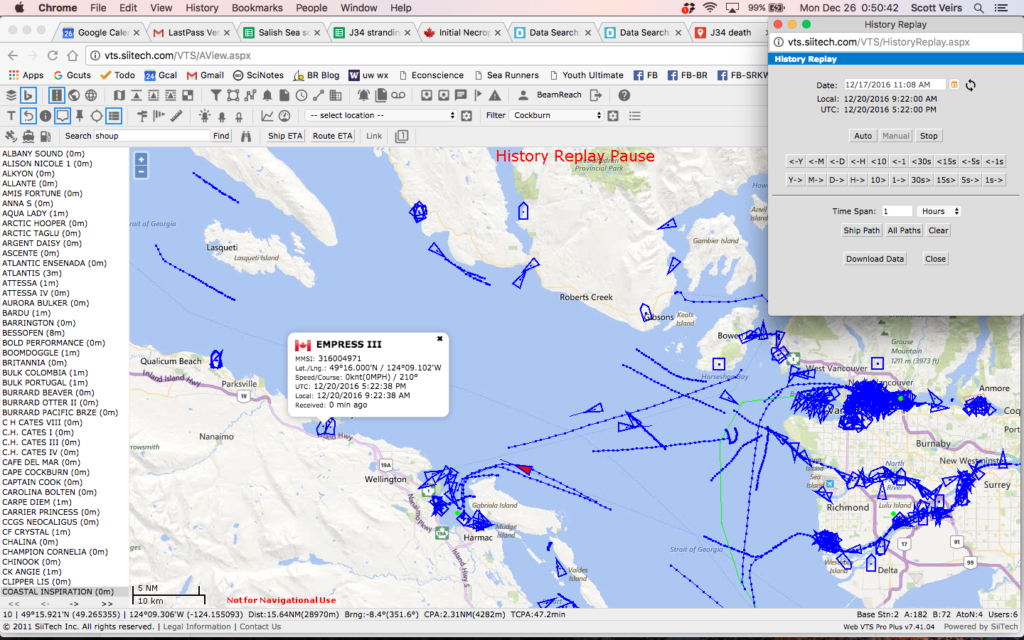

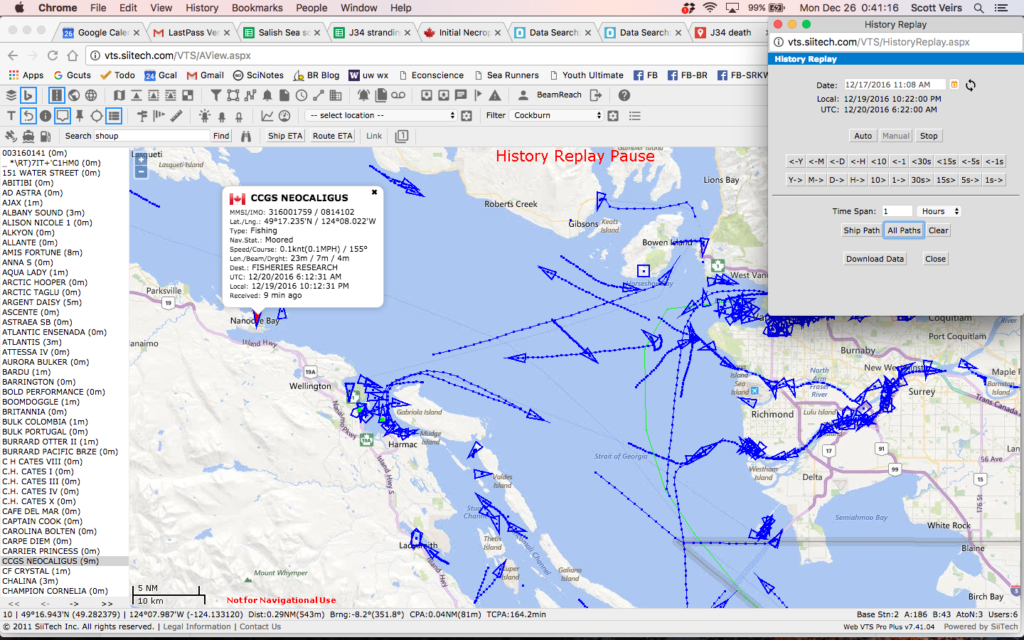

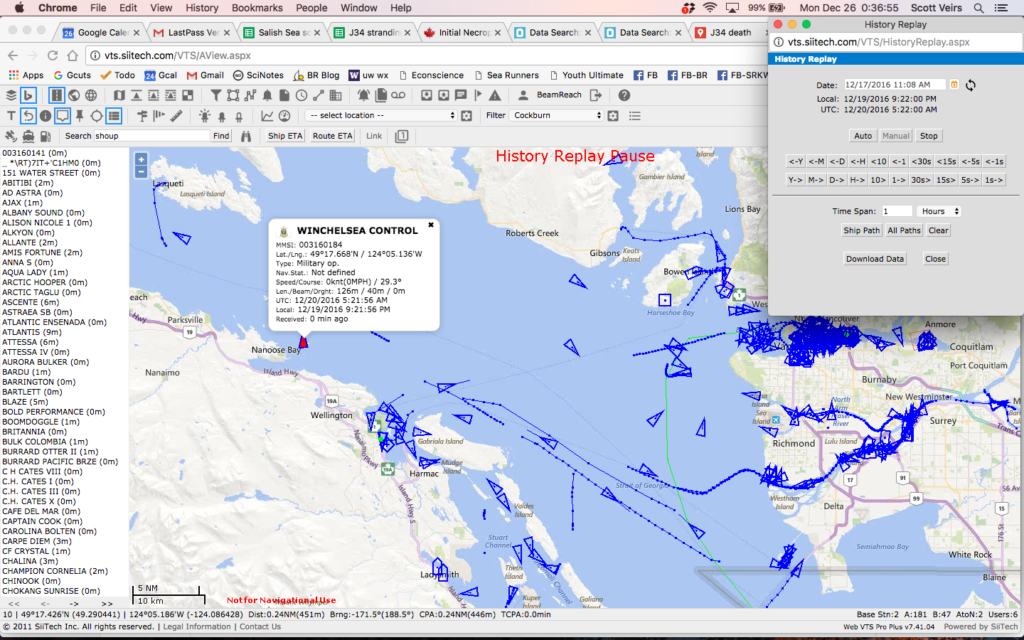

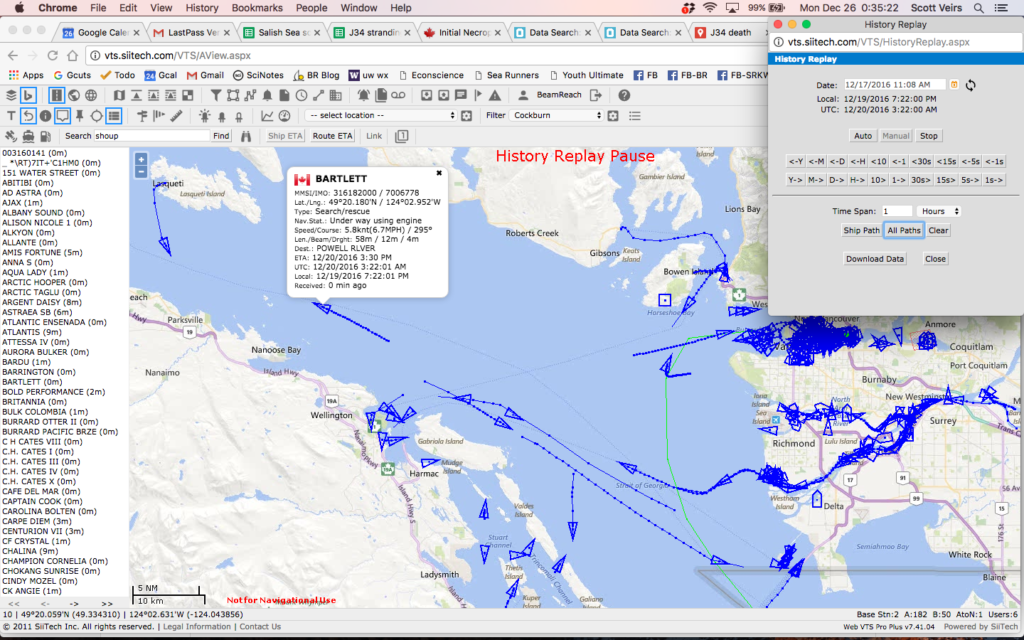

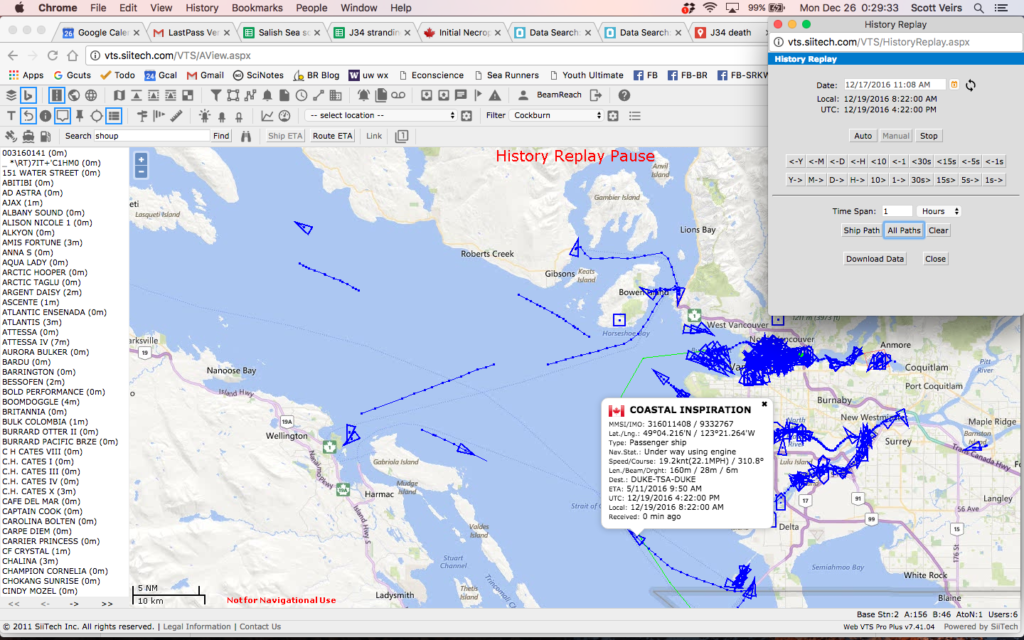

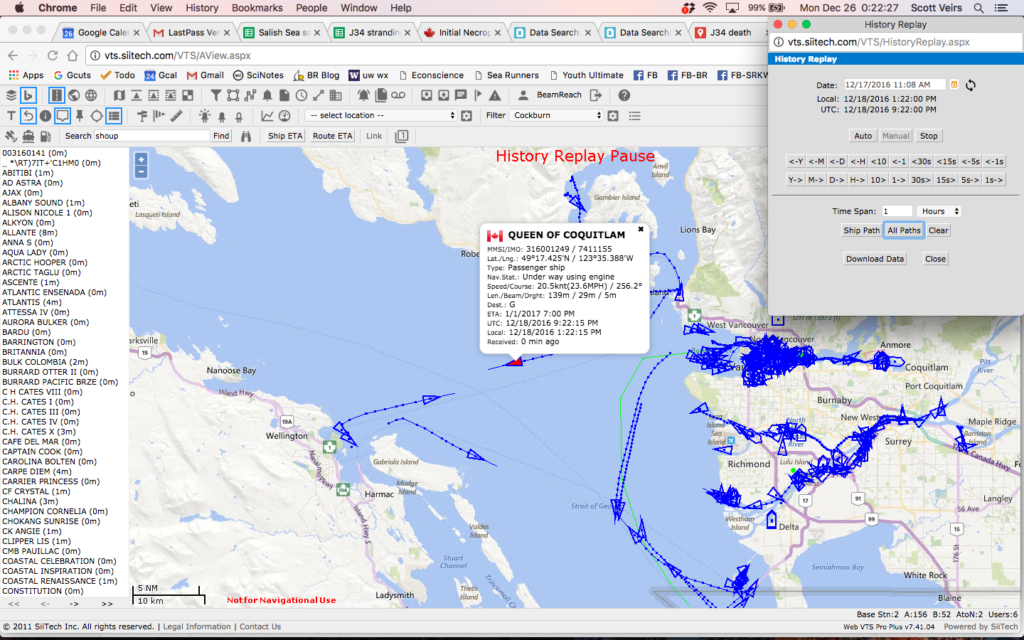

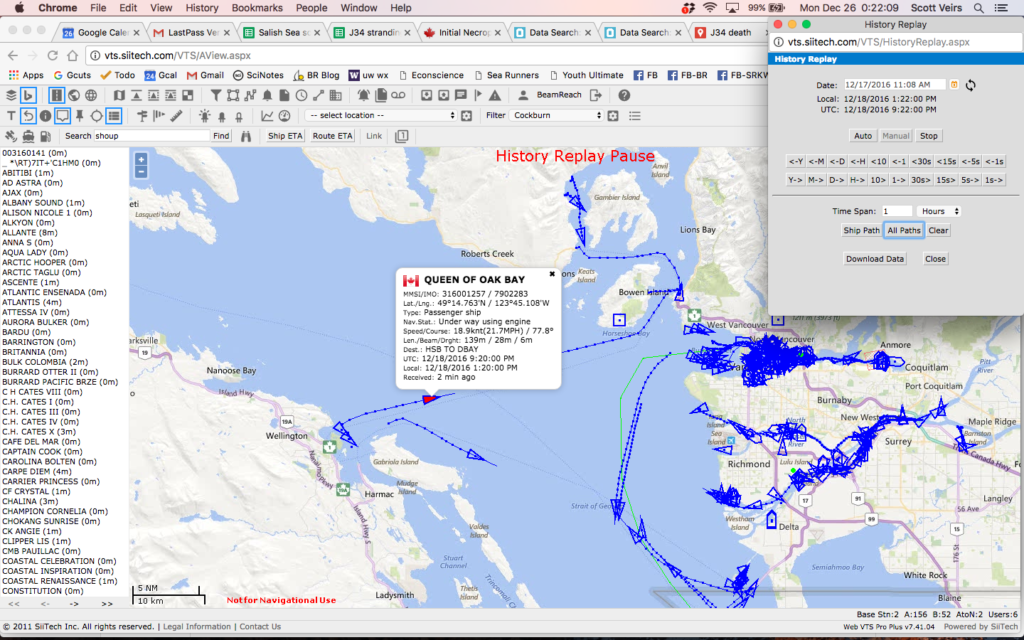

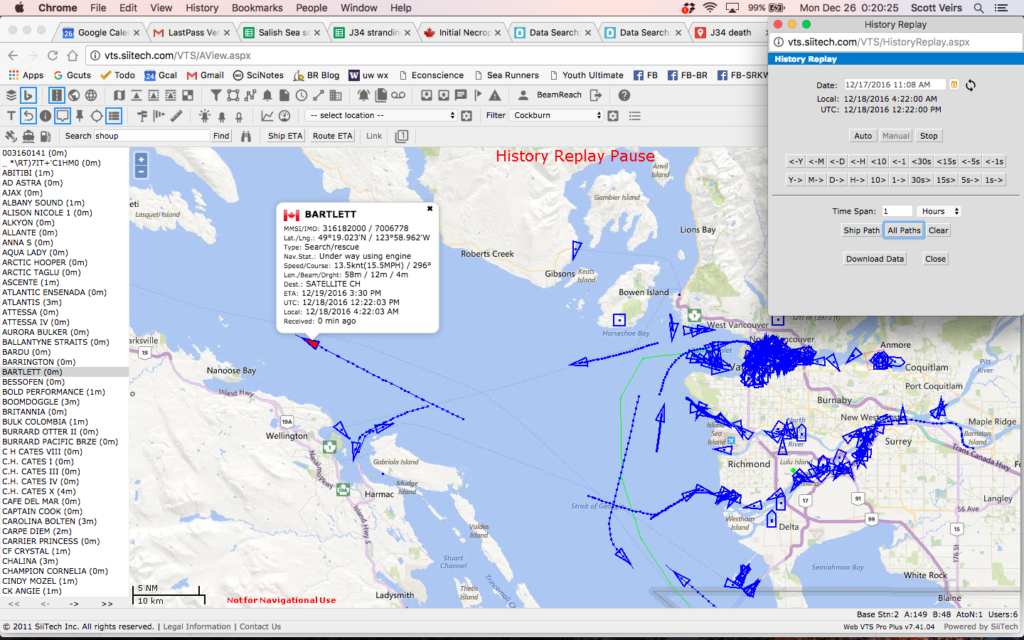

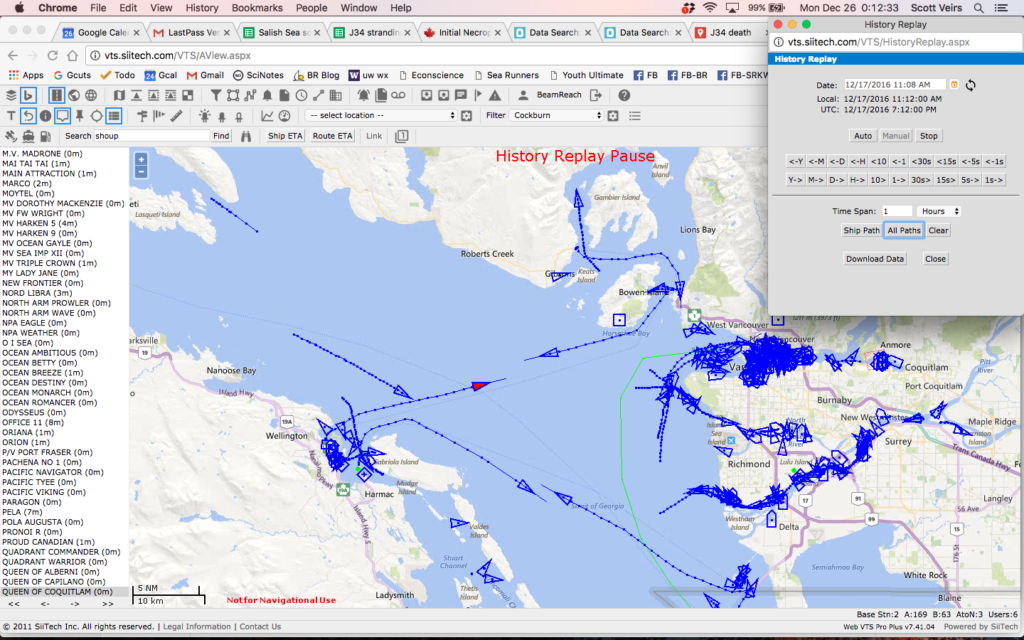

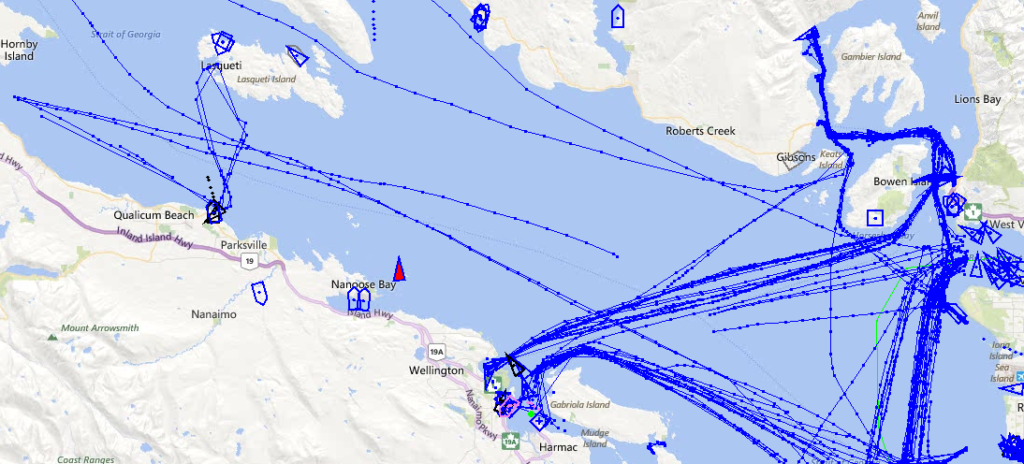

These text-based descriptions of the discovery led us in late December 2016 to query a Automated Identification System database (Siitech) for vessel location information. We searched the results for tugs and Canadian governmental vessels in the vicinity of Sechelt. We also noticed a strange pattern of AIS vessels (stationary?) showing up and disappearing within the Whiskey Golf area near Nanoose Bay (present ~12/17; absent until ~12/19 20:30; present intermittently between 12/20 9:00; details in the chronology spreadsheet).

The following screen shots summarize the relevant results. (Need to add captions and re-order more logically…)

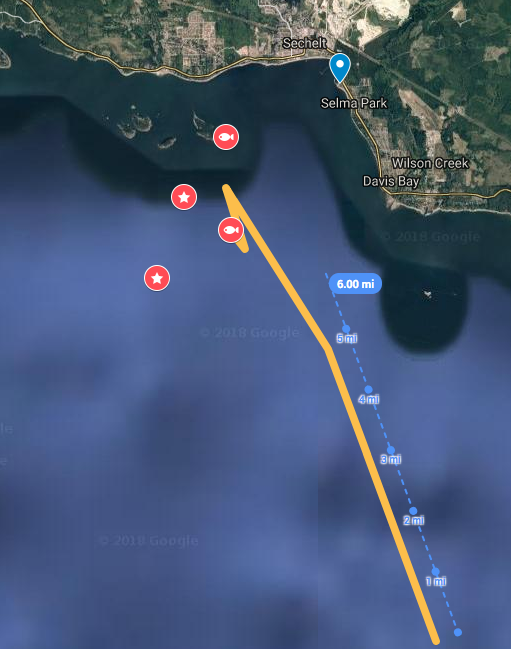

The key findings were multiple tugs in the vicinity around 10 a.m. on 12/21 that could have reported the sighting first that morning. About the same time the Canadian Coast Guard vessel Cape Cockburn appeared to search inshore of the Trail Islands and then intercept one of the path of one of the tugs. Afterwards the Cape Cockburn track is nearly stationary (indicating the period when they were securing the carcass for a tow), and then it proceeds directly to the mainland indicating the approximate position of the beach where the necropsy was performed.

Probable trajectory of the carcass

Pending more detailed analysis with the best available current observations, we take the prevalence of southerly wind events in the days prior to the stranding as sufficient justification to add a rough direction of drift to the J34 stranding map. The yellow line (screen shot below) represents the trajectory and is extending from the first high-confidence carcass location (the Cape Cockburn AIS lat/lon on 21 Dec 2016 at 10:42).

An important future step will be to review the literature regarding drift modeling for other killer whales or cetaceans. What is best methodology for modeling post-mortem transport? Was it used and was it consistent between the J34 and L112 strandings? What role could advances in 3D hydrodynamic current models of the Salish Sea (PNNL | WA Dept. of Ecology) play in stranding investigations — past and future?

It will be very valuable to learn what indications, if any, in the final necropsy report can constrain how long J34 may have drifted, and how long and fast he may have swum after being injured. With this added information we may be able to determine if the trajectory overlaps with the Whiskey Golf naval testing/training area, the Horseshoe Bay – Nanaimo ferry route, other regions of high vessel-density around Vancouver, and/or distributions of other marine mammals.

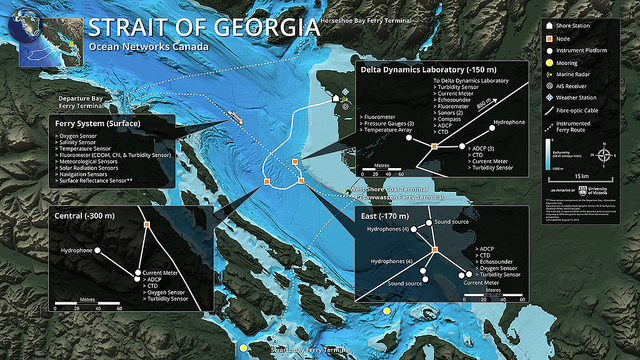

Acoustic observations

Due to proximity of the stranding location and preliminary trajectory to the Whiskey Golf area, and to acoustically establish presence/absence of marine mammals, we completed an initial evaluation of a subset of the hydrophone data that might help inform the stranding of J34. Most importantly we detected the calls of SRKWs on 12/17/2016 at ~12:11:02 off Fraser River mouth, BC. The calls were faint, but very likely from J pod based on confirmation of call (S1, S2, S3s, possibly an S7, and a S17 later) by Monika Wieland.

On 12/17/2016 at 11:31:02 we noted strange tonal sounds that may have been a distant power boat, but could also have possibly been related to mid-frequency active sonar. And on 12/18/2016 at 22:01:02 we heard a low-frequency rumble — which might possibly be interpreted as a reverberating detonation. These potential military noise signals, however, were very faint and we have little confidence in their interpretation at this point. Finally, we heard humpback calls on 12/19/2016 at ~9:41:02, indicating the presence of other marine mammals in the vicinity of the Fraser river delta two days before J34 was secured.

In addition to a more thorough acquisition and careful analysis of ONC hydrophone data, it would be valuable to ascertain whether other hydrophone systems may have gathered additional information about the case of J34. Possible sources to investigate include:

- SIMRES data from their hydrophones on Saturna Island

- Any autonomous recorders that may have been deployed at the time (e.g. SMRU or JASCO mooring(s) related to the Terminal 2 expansion?)

- Any DFO hydrophones in the vicinity (e.g. in/near Active Pass, or in/near Nanaimo)

- Any Naval recordings from the relevant time period (e.g. assets associated with the Whiskey Golf area and/or Nanoose?)

Any military testing/training activities planned? Were there any other intense sonic events reported in the week prior to the stranding, like earthquakes or lightning strikes?

Necropsy report(s)

An impressive team of experts conducted a necropsy on the beach more-or-less immediately. The necropsy was performed by Dr. Stephen Raverty. Also present were DFO Pacific Region Marine Mammal Coordinator Paul Cottrell, other DFO staff and biologists, as well as staff from the Vancouver Aquarium.

20 Dec 2018 note:

Because the final necropsy report has not been published, despite repeated requests by Beam Reach for updates from DFO, this section currently presents only the initial results, a summary of the final report, observations from other experts, and diverse photographic and video documentation from all sources that we’ve been able to find. Luckily there were some excellent videos taken by some of those present on the beach, but we’re eager for a full assessment of the necropsy results as soon as possible. As Canada is currently forming multiple Technical Working Groups to make short- and long-term recommendations for the conservation of endangered SRKWs, now is a good time to learn as much as we can from J34 and ensure that prevention of further “blunt force trauma” to SRKWs is included in the 2019 conservation efforts.

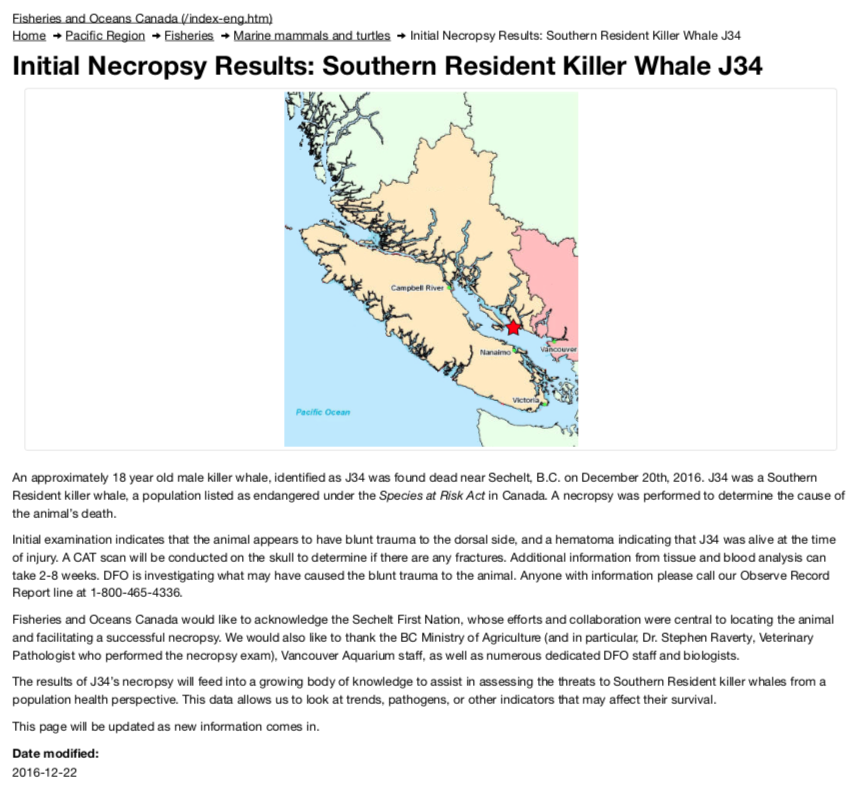

DFO Initial Necropsy Results

The DFO “Initial Necropsy Results” were available online, both via the DFO web page (via this link; broken in 2018) and the NOAA stranding page (via the same link; broken in 2018). Luckily, we archived it at the time so can provide it here — both as text & a screen shot (both below), as well as a PDF.

An approximately 18 year old male killer whale, identified as J34 was found dead near Sechelt, B.C. on December 20th, 2016. J34 was a Southern Resident killer whale, a population listed as endangered under the Species at Risk Act in Canada. A necropsy was performed to determine the cause of the animal’s death.

Initial examination indicates that the animal appears to have blunt trauma to the dorsal side, and a hematoma indicating that J34 was alive at the time of injury. A CAT scan will be conducted on the skull to determine if there are any fractures. Additional information from tissue and blood analysis can take 2-8 weeks. DFO is investigating what may have caused the blunt trauma to the animal. Anyone with information please call our Observe Record Report line at 1-800-465-4336.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada would like to acknowledge the Sechelt First Nation, whose efforts and collaboration were central to locating the animal and facilitating a successful necropsy. We would also like to thank the BC Ministry of Agriculture (and in particular, Dr. Stephen Raverty, Veterinary Pathologist who performed the necropsy exam), Vancouver Aquarium staff, as well as numerous dedicated DFO staff and biologists.

The results of J34’s necropsy will feed into a growing body of knowledge to assist in assessing the threats to Southern Resident killer whales from a population health perspective. This data allows us to look at trends, pathogens, or other indicators that may affect their survival.

This page will be updated as new information comes in.

Date modified:

2016-12-22

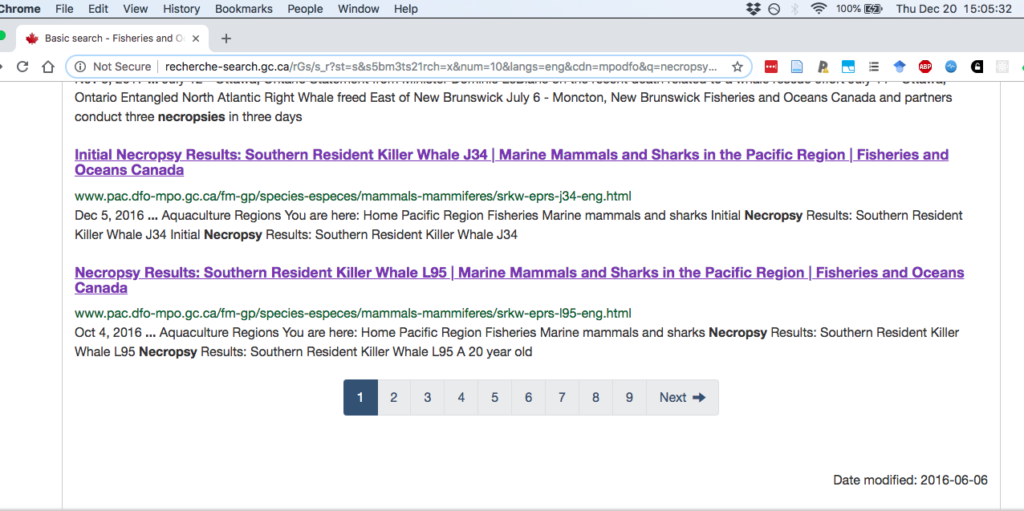

As of December 20, 2018, the URL of the initial necropsy results appears to be broken, e.g.:

Clicking on the links to the initial report currently resolves to the general Canada-wide DFO home page — both either the relevant DFO web site, or the NOAA West Coast SRKW stranding site (where the link was promptly posted and was functional in December, 2016).

Observations from Ken Balcomb (via email)

Based on a review of the initial necropsy results and associated video, and possibly other press sources, Ken Balcomb volunteered the following in an email (03 Jan 2017):

“I would not characterize the blubber thickness as being “normal†as reported, based upon what I see in the video; but, I presume that blubber thickness was measured at numerous locations and samples taken for lipid content analysis. The blubber looks a bit thin to me, and dry? similar to J32. The discoloration that is apparent ventrally is similar to that I have previously previously observed for L112 and L60 (the former from photos and the latter from participation in the necropsy).”

Insights from emails with Stephen Raverty and Paul Cottrell (2016-2018)

- 27 Dec 2016: “DFO has enforcement officers investigating this event and additional information may come to light. We plan to have CT scans conducted of J34’s skull to assess for possible ear pathology and have harvested 1 ear for diagnostic evaluation.” “The necropsy is complete and all samples collected.”

- 05 Jan 2017: “There are still some aspects of the investigation that are underway and we need the additional findings to complete the document…. we are trying to retrieve buried bones to evaluate.”

- 21 Mar 2018: “animal had a significant dorsolateral hemorrhage on the left side, indicating blunt force trauma. See broad summary below.”

Summary of the final report by Paul Cottrell

The gross lesions are consistent with blunt force trauma and based on the anatomic site of impact, the sustained injuries would have contributed significantly to the demise of this animal. The tracking hemorrhage throughout the subcutis of the head suggests that the animal would have survived the initial trauma for a period time, prior to death. Although the brain was too autolyzed to assess for hemorrhage (coup contra-coup), a few bone spicules and sheaves up to 3-4 cm long were interspersed within the brain tissue. Based on qualitative assessment, the animal was considered in moderate to good body condition and there were no apparent lesions or abnormalities which may have predisposed this animal to injury.

GROSS DIAGNOSES:

1). Thorax, left dorsolateral: Hemorrhage, subcutaneous, muscular, fascial and paravertebral, severe, segmental, acute with variable amounts of edema fluid

2). Skull: Hemorrhage, subcutaneous, marked, bilateral to circumferential, tracking

3). Occipital region, rostrolateral blowhole, and acoustic fat: Hemorrhage, marked, multifocally extensive, acute

2016 DFO list of SARA incidents

The stranding of J34 was not noted in the 2016 annual report of DFO’s Marine Mammal Response Program (PDF).

Videos

Photographs (and video screen shots)

These images are either screen grabs from videos or photographs put into the public domain. We will try to caption and credit them appropriately in future revisions of this post.

Towing to shore

Necropsy images

Press coverage

- 22 Dec 2016 — https://westseattleblog.com/2016/12/another-southern-resident-killer-whale-death-orca-j34-found-on-b-c-beach/

- 23 Dec 2016 — https://www.king5.com/article/news/local/endangered-orca-died-of-blunt-force-trauma-necropsy-finds/377075629

Discussion:

Hypotheses to discuss w/differential evidence

- Vessel strike causes blunt force trauma and death

- Another mechanism (antagonistic or defensive whale?) causes blunt force trauma and death

- Blast (or sonar?) causes initial injury (blast trauma) and death

- Blast, sonar, or other damaging sound causes initial injury (PTS), reducing animal’s ability to avoid strikes; vessel causes second injury (blunt force trauma) and death

- Loud noise causes initial injury (TTS), reducing animal’s ability to avoid strikes; vessel causes additional injury (blunt force trauma) and death

- Which of the non-acoustic causes could result in evidence that is also consistent with blast trauma, and/or PTS, and/or TTS?!

A major outstanding task is to aggregate and review the literature on: underwater blast trauma in marine mammals; the signs of TTS and/or PTS in killer whale hearing systems; blunt force and other trauma caused by ships and/or boats striking marine mammals. [When/why is there blood in the pan bone’s acoustic fat? What resolution of CT scan is needed to resolve damage to ears/bullae due to blunt force trauma versus acoustic trauma?]

Key evidence to discuss

- Initial necropsy report: “blunt trauma to the dorsal side, and a hematoma indicating that J34 was alive at the time of injury.”

- Final necropsy (summary): “gross lesions are consistent with blunt force trauma and based on the anatomic site of impact, the sustained injuries would have contributed significantly to the demise of this animal”

Overall J34 map

Link: interactive Google map

Overall J34 chronology

Link: J34 stranding interactive Google spreadsheet

Conclusions:

Without the final necropsy report published and fully reviewed, it is too soon to draw any conclusions about what killed J34…

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook