With transient killer whales in the area and the whereabouts of J and L pods (and their many newborns!) unknown, we were concerned to hear that active sonar was utilized late in the morning on Wednesday, January 13, in Haro Strait — critical habitat for species in both Canada and the U.S. At the same time, military training activities were planned or taking place on both sides of the border. This is what it sounded like underwater along the western shoreline of San Juan Island —

Audio Player

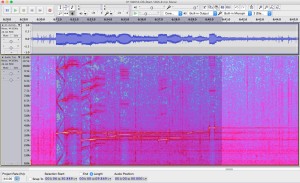

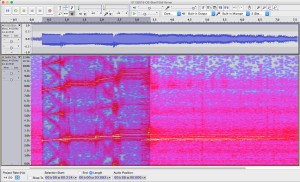

Complex sonar sequence recorded in Haro Strait on 1/13/2016 via the Orcasound hydrophone (~5km north of Lime Kiln State Park).

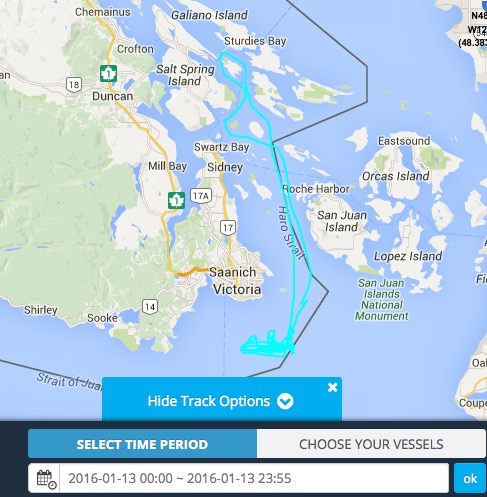

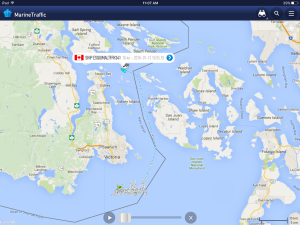

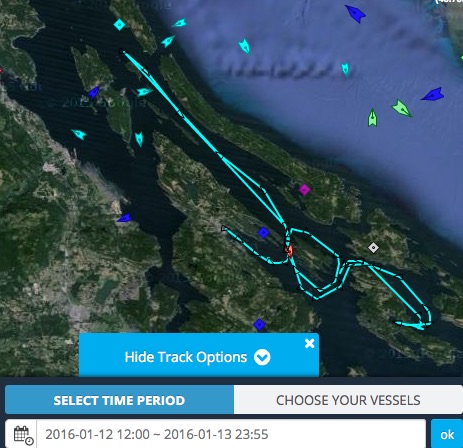

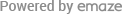

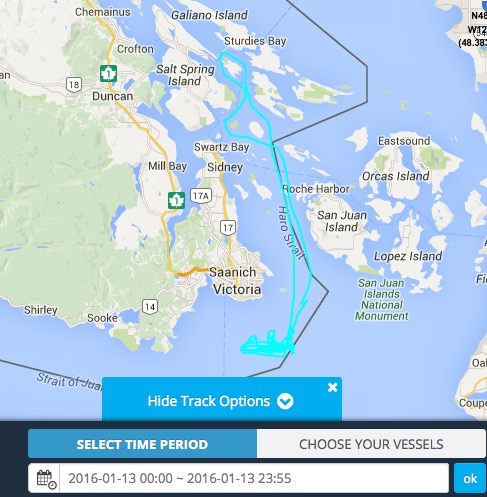

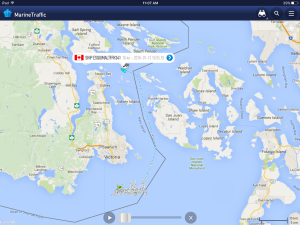

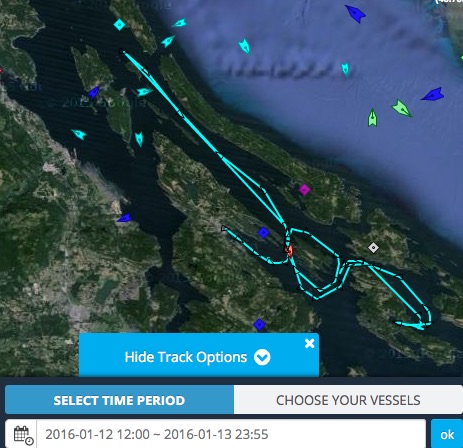

When the sonar was heard and recorded by members of the Salish Sea Hydrophone Network the Canadian Naval vessel HMCS Ottawa was observed (via AIS) transiting Haro Strait in U.S. waters about 10-20 km north of the hydrophones.

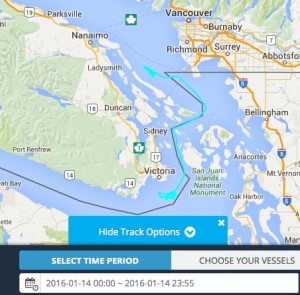

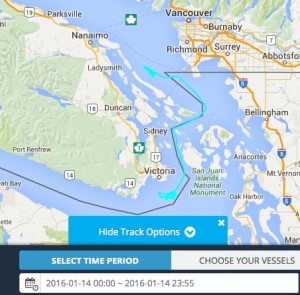

This juxtaposition led us to initially assert that the Ottawa — a Halifax class frigate which carries active sonar — was the source of the sonar pings, reinforced by the activation of the test range (area Whiskey Golf off Nanaimo) on 1/12 and 1/14. However, a proactive call to Beam Reach on 1/14/16 from Danielle Smith, Environmental Officer for Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt, suggested that the Ottawa was not the source. Specifically, she stated that active sonar use was not in their plan when they last departed. She also said she spoke directly with the Ottawa’s Commanding Officer who confirmed with the crew that the transducers were not lowered, and that therefore there was no way their SQS-510 (medium frequency search sonar system) could have transmitted (e.g. sometimes calibrations underway go unreported). Finally, she communicated that their senior sonar techs were confident that the recorded frequencies were not consistent with the Ottawa’s 510 system. When asked, she confirmed that the sonar system had not been upgraded since it was last recorded during the 2012 vent in which the Ottawa disturbed and possibly damaged the endangered Southern Resident Killer whales.

Other sources of information also suggest that the U.S. Navy may have been the source of the sonar pings.

First and foremost, the sonar pings are distinct from the active mid-frequency SQS-510 sonar used by the Ottawa in February, 2012. Instead, they sound similar to, but are more complex than the SQS-53C pings emitted by the U.S. destroyer Shoup on May 5, 2003. [They were also coincident with many individual broadband pings spaced about 6.6 seconds apart. Were these made by the vessel with the active sonar, or a different one?]

Furthermore, comparison of the times of the recorded sonar pings and available AIS tracks suggests that the sonar was recorded when the Ottawa was located between the north Henry Island and Turn Point at the northwest tip of Stuart Island. If the source was the Ottawa, why would it have utilized sonar only while within U.S. waters (about 1-2 km east of the International Boundary). During this period, the Ottawa was about 8-16 km north of the recording hydrophones. Pending computation of the calibrated received levels, the qualitative intensity of the received pings suggests that the source was closer than the Ottawa’s AIS positions allow.

Smith’s statements and these observations raise a key question:Â were U.S. vessels in the area emitting these sounds that are similar to those emitted by the US destroyer Shoup in 2003?

This possibility is alarming because the U.S. Navy has refrained from training with active sonar within the Salish Sea since the Shoup sonar incident of 2003 (which disturbed endangered Southern Residents, as well as a minke whale and harbor porpoises). (The U.S. Navy has tested sonar since the Shoup incident: during the San Francisco submarine event of 2009 and the Everett dockside event in 2012.) Also, the U.S. Navy more recently has agreed to minimize the impacts of its mid-frequency sonar.

Portending a worrisome trend, at the start of 2016 news surfaced that the U.S. Navy planned operations in the Pacific Northwest that might include “mini-subs” and beach landings beginning in mid-January, 2016. No recent AIS tracks of US military vessels have been archived by marinetraffic.com, suggesting that the Navy vessels’ AIS transceivers may have been turned off based on their mission.

Visual observations demonstrate that U.S. Naval ships were active on 1/13/20016. At least one U.S. Naval ship, possibly a frigate, was seen departing Everett around mid-day by Orca Network. Slightly earlier, between 10:30 and 11:30 a.m Howard Garrett of Orca Network saw two Navy ships transiting northward up Admiralty Inlet about 15 min. apart. The first one looked like the Shoup, complete with the cannon on the bow; the second looked more like a supply ship.

(1/17/16 update: A citizen scientist observed two Naval ships southbound in Haro Strait between Turn Point and D’Arcy Island at around 10:45 a.m. — roughly coincident with the sonar heard on the nearby Orcasound hydrophone. 1/19/16: Navy Region Northwest has confirmed a U.S. Naval ship was “in the area…”)

Update 1/22/16: Navy Region Northwest Deputy, Public Affairs, Sheila Murray stated in an email to Beam Reach,

“A U.S. Navy DDG was transiting within the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the U.S. side of the waterway (not in or near the Haro Strait). The DDG confirmed sonar use consistent with recordings on the Beam Reach Facebook page for a brief period of time, approximately 10 min. There were trained lookouts stationed during this event. No marine mammals were sighted during the activity and no marine mammal vocalizations were detected by passive acoustic monitoring. The ship was briefly operating its sonar system for a readiness evaluation in order for the ship to deploy in the near future.”

It is not clear whether the DDG (Guided Missile Destroyer) was one of the Everett-based ships — the Shoup or Momsen — or if it was based elsewhere (e.g. one of the 15 destroyers stationed in San Diego). [Update 1/25/2016: Navy Region Northwest has, however, re-directed a question from Beam Reach regarding the procedures followed by the ship to the Third Fleet (based in San Diego) suggesting that the DDG may have been based in California.]

Update 2/4/16: Lt. Julianne Holland, Deputy Public Affairs Officer Commander, U.S. Third Fleet responded to a question posed by Beam Reach,

Below is the response to your question: Did the DDG obtain permission from the Commander of the Pacific Fleet in advance of this use of MFAS in Greater Puget Sound?

The Navy did not anticipate this use within the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The use of sonar was required for a deployment exercise that was not able to be conducted outside of the Strait due to sea state conditions. The Navy vessel followed the process to check on the requirements for this type of use in this location, but a technical error occurred which resulted in the unit not being made aware of the requirement to request permission. The exercise was very brief in duration, lasting less than 10 minutes, and the Navy has taken steps to correct the procedures to ensure this doesn’t occur again at this, or any other, location. The Navy also reviewed historical records to confirm this event has not occurred before and was a one-time occurrence within the Puget Sound/Strait of Juan de Fuca. The Navy reported the incident to NMFS and NMFS determined that no modifications to the Navy’s authorization are needed at this time.

Below is a chronology of events, wildlife sightings, and acoustic analysis that we hope will help document the event, including the source of the sonar and any impacts on marine life of the Salish Sea.

Key events (local time, PST):

Tue 1/12/16 14:30 PST: Ottawa in search pattern all afternoon and night (1-7 knots, east of Constance Bank)

Wed 1/13/16 09:00 PST: Ottawa moves north into Haro Strait

Wed 1/13/16 10:00 PST: Ottawa enters U.S. waters between False Bay and Discovery Island, proceeds north

Wed 1/13/16 10:45 PST: Intense sonar pings recorded on the Orcasound hydrophone (originating from a U.S. destroyer in the Strait of Juan de Fuca)

Wed 1/13/16 11:00 PST: Ottawa leaves U.S. waters near Turn Point, Stuart Island

Detailed Chronology (public Google spreadsheet):

Acoustic recordings and analysis

8 minute recordings from Lime Kiln and Orcasound

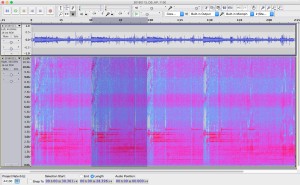

Jeanne Hyde provided 2 recordings — each about 8 minutes long — of a sequence of sonar pings. The first is from the Lime Kiln lighthouse hydrophone (but we believe there is some drift in the time base, so this recording should not be used to assess event timing, like sonar initiation, duration, or ping intervals) —

Lime Kiln 8-minute recording (10:41)

Audio Player

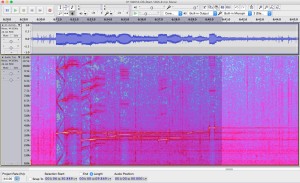

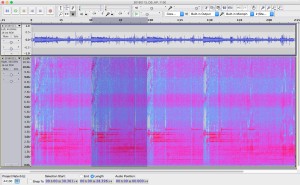

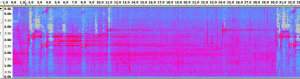

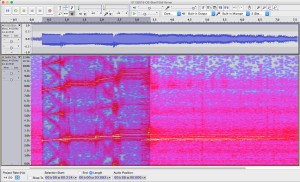

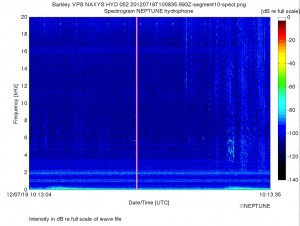

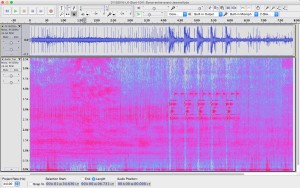

Spectrogram of 8-minute recording from the Lime Kiln hydrophone.

— the second is from the Orcasound hydrophone (about 5 km north of Lime Kiln) —

Orcasound 8-minute recording (10:55)

Audio Player

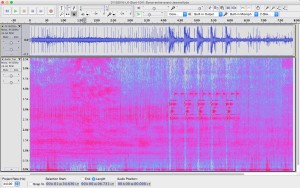

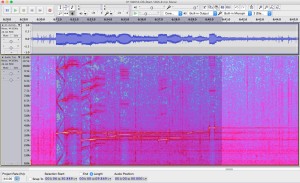

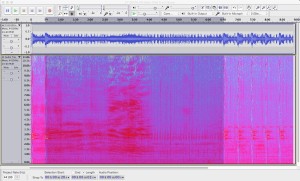

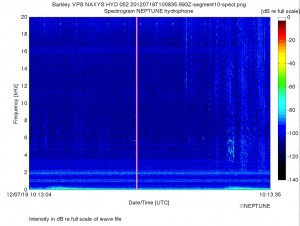

Spectrogram of 8-minute recording from the Orcasound hydrophone.

Assuming that drift in the Lime Kiln recording has corrupted its time base, we use the Orcasound to establish timing of the event. Overall, the event consists of a pattern of broadband pulses and ~30-second sequences of frequency modulated (FM) slide and narrowband continuous wave (CW) pulses. The ~9-minute pattern was: two simple, ascending FM+CW sequences, 52 broadband pulses (2.5-3.0 kHz) about 6.7 seconds apart, and then 5 more FM+CW sequences.Â

The initial and final FM+CW sequences were distinct. The first two were relatively simple and consisted of: a 2.5-2.6 kHz rise for ~0.5 seconds, 2.75 kHz tone for ~1 second, another 0.5 second rise from 2.85-2.95 kHz, and finally a 3.1 kHz tone for ~1 second. The more complicated sequence that is repeated 5 times at the end of the sonar event (around 11:00-11:03 a.m.) is described below (in the section that makes a comparison with SQS-53C sonar sequences emitted by the Shoup in 2003).

The broadband pulse echoes were audible and were received on average 3.4 seconds after the direct path pulse. This time delay indicates a mean extra distance traveled of about 5 kilometers, though there was a clear trend from about 5.7 to 4.4 km over the course of the 52 pings.

Further quantitative analysis of the acoustic data is included in the 13 Jan 2016 sonar chronology Google spreadsheet. The larger data files are archived and shorter clips and associated spectrograms are embedded below.

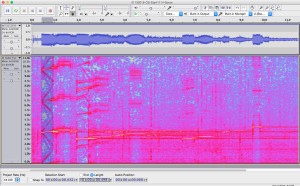

Sonar sequence repeated 5 times around 11:00

Below is a 2-minute recording of the Orcasound hydrophone (by another hydrophone network citizen scientist) at 11 a.m. on 1/13/16 containing 4 sonar ping sequences. Each sequence lasts 30 seconds and contains a series of complex rising tones followed by single 3.75 kHz tones at about 9 and 22 seconds into the sequence.

Audio Player

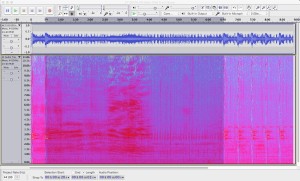

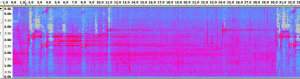

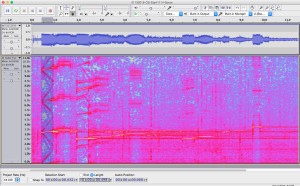

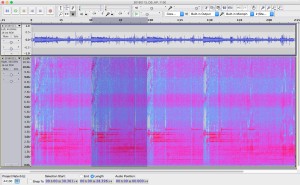

Spectrogram of the final 4 repetitions of the more complex sonar sequence.

Spectrogram showing the detailed pattern of sounds during one of the more complex sonar sequences.

Individual sonar ping at 10:55

Recorded and provided by Jeanne Hyde, this ascending sonar sequence is relatively simple —

Audio Player

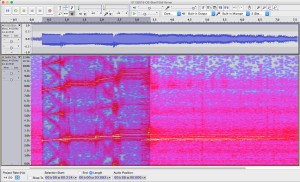

Spectrogram of a single ping on the Orcasound hydrophone at 10:55 a.m.

Individual sonar ping at 11:00 (1:14 into ~2hr 26 min recording)

In comparison, this recording (provided by Jeanne Hyde) captures one of the more complex sonar sequences —

Audio Player

Spectrogram of 0.5 second sonar pings at 3.25, 6.5, and 9.75 kHz recorded on the Orcasound hydrophone.

Comparison with SQS-53C sonar pings from 2003 Shoup event

This historic recording from 2003 is similar (relatively abbreviated) to the single ping at 10:55 —

Audio Player

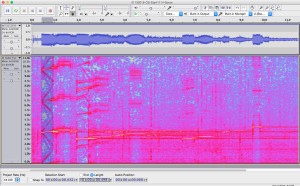

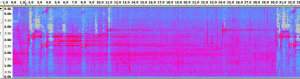

Spectrogram of a single ping from the SQS-53C sonar during the 2003 Shoup incident.

In comparison, here’s one of the more complex sonar sequences observed on 1/13/16 —

Audio Player

Complex sonar sequence recorded in Haro Strait on 1/13/2016.

Overall, the ~10-second sequence has fundamentals and pure tones are between 2.5-3.75 kHz. This makes it distinct (lower frequencies) from the 6-8 kHz tones of Canadian SQS-510 system.

The initial 0.5-second tone has fundamental at 3.20 kHz rising to 3.35 kHz, with intense harmonics at 6.43-6.60 and 9.60-9.90 kHz.  This is followed by a 1.0-second pure tone at 3.45 kHz.

A second 0.5-second tone rises from 2.50-2.63 kHz, with a weak first harmonic at 5.0-5.2 kHz and a moderately intense second harmonic at 7.5-7.8 kHz. This is followed by a 1.0-second pure tone at 2.73 kHz.

There’s a third pair of rising and pure tones at intermediate frequencies, followed by a pause for reverberations/listening, and then a repeat (at lower source level?) of the second and initial phrases. Finally, there is an ending 0.5-second pure tone at 3.75 kHz.

Ship tracks and descriptions

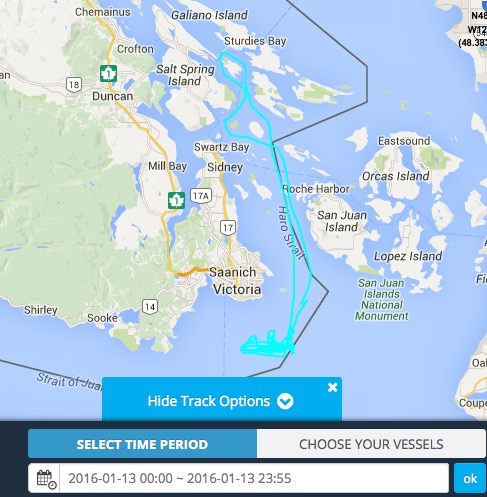

The Canadian frigate Ottawa was observed in Haro Strait at the time of the sonar pings. If the time of the recordings and AIS locations are accurate, then the Ottawa was approximately 8-16 km north of Lime Kiln and Orcasound when the sonar sounds were recorded at those hydrophone locations.

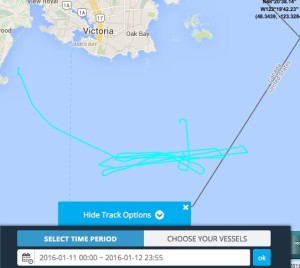

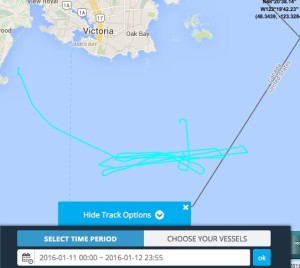

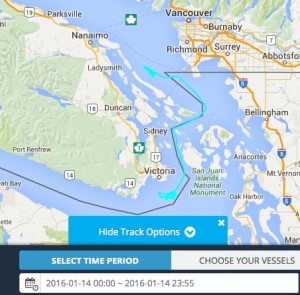

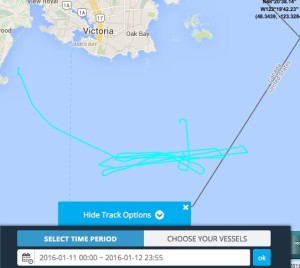

AIS track of the Ottawa on 1/11 to 1/12.

AIS track of the Ottawa on 1/13.

AIS track of the Ottawa on 1/14.

Alternative Ottawa track map

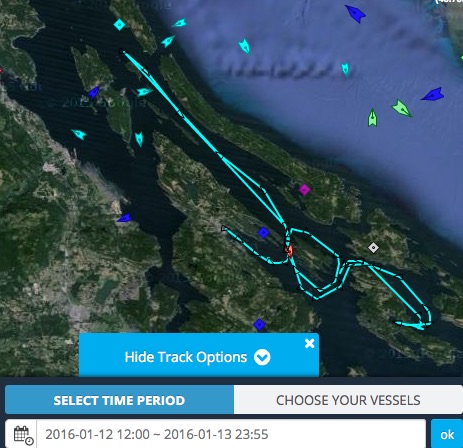

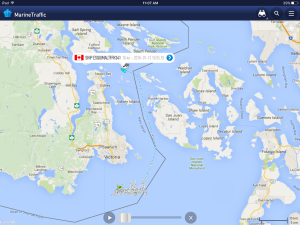

The Canadian Orca class patrol vessel, Caribou 57, was also active and tracked on AIS. From Tuesday 1/12 noon through 1/13 it was patrolling withing the southern Gulf Islands.

Track of the patrol vessel Caribou 57 on 1/12-13.

Possible US Naval ships in/outbound from Everett on 1/13/2016 (Skunk Bay web cam):

Read More

NOTE: Due to new information provided by the Canadian Navy, this post has been archived.

A new version with the most up-to-date and accurate information is available here — http://www.beamreach.org/2016/01/14/navy-starts-2016-pinging-in-the-pool

With transient killer whales in the area and the whereabouts of J and L pods (and their many newborns!) unknown, we were concerned to hear that active sonar was utilized late in the morning on Wednesday, January 13, in Haro Strait — critical habitat for species on both sides of the border. At the same time, military training activities were planned or taking place on both sides of the border. At the time the sonar was heard and recorded by members of the Salish Sea Hydrophone Network the Canadian Naval vessel HMCS Ottawa was transiting Haro Strait in U.S. waters.

This juxtaposition led us to initially assert that the Ottawa — a Halifax class frigate which carries active sonar — was the source of the sonar pings, reinforced by the activation of the test range (area Whiskey Golf off Nanaimo) on 1/12 and 1/14. However, a proactive call to Beam Reach on 1/14/16 from Danielle Smith, Environmental Officer for Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt, suggested that the Ottawa was not the source. Specifically, she stated that active sonar use was not in their plan when they last departed. She also said she spoke directly with the Ottawa’s Commanding Officer who confirmed with the crew the transducers were not lowered, and that therefore there was no way their SQS-510 (medium frequency search sonar system) could have transmitted (e.g. sometimes calibrations underway go unreported). Finally, she communicated that their senior sonar techs who said the recorded frequencies were not consistent with the Ottawa’s 510 system. When asked, she confirmed that the sonar system had not been upgraded since it was last recorded during the event in 2012 in which the Ottawa disturbed and possibly damaged the endangered Southern Resident Killer whales.

Other sources of information also suggest that the U.S. Navy may have been the source of the sonar pings.

First and foremost, the sonar pings are distinct from the active mid-frequency SQS-510 sonar used by the Ottawa in February, 2012. Instead, they sound similar to, but are more complex than the SQS-53C pings emitted by the U.S. destroyer Shoup on May 5, 2003.

They were also coincident with many individual broadband pings (classic submarine-movie ones) spaced about 6.6 seconds apart. Were these made by the vessel with the active sonar, or a different one?

Finally, comparison of the times of the recorded sonar pings and available AIS tracks suggests that the sonar was recorded when the Ottawa was located between the north Henry Island and Turn Point at the northwest tip of Stuart Island. If the source was the Ottawa, why would it have utilized sonar only while within U.S. waters (about 1-2 km east of the International Boundary). During this period, the Ottawa was about 8-16 km north of the recording hydrophones. Pending computation of the calibrated received levels, the qualitative intensity of the received pings suggests that the source was closer than the Ottawa’s AIS positions allow.

Smith’s statements and these observations raise a key question:Â were U.S. vessels in the area emitting these sounds that are similar to those emitted by the US destroyer Shoup in 2003?

This possibility is alarming because the U.S. Navy has refrained from training with active sonar within the Salish Sea since the Shoup sonar incident of 2003 (which disturbed endangered Southern Residents, as well as minke whale and harbor porpoises). (The U.S. Navy has tested sonar more recently, however, during the San Francisco submarine event of 2009 and the Everett dockside event in 2012.) Also, the U.S. Navy more recently has agreed to minimize the impacts of its mid-frequency sonar.

Portending a worrisome trend, at the start of 2016 news surfaced that the U.S. Navy planned operations in the Pacific Northwest that might include “mini-subs” and beach landings beginning in mid-January, 2016. At least one U.S. Naval ship, possibly the destroyer Shoup, was seen departing Everett around mid-day by Orca Network. No recent AIS tracks of US military vessels have been archived by marinetraffic.com, suggesting that the Navy vessels’ AIS transceivers may have been turned off based on their mission.

Below is a chronology of events, wildlife sightings, and acoustic analysis that we hope will help document the event, including the source of the sonar and any impacts on marine life of the Salish Sea.

Rough Chronology (local time, PST):

Tue 1/12/16 14:30 PST: Ottawa in search pattern all afternoon and night (1-7 knots, east of Constance Bank)

Wed 1/13/16 09:00 PST: Ottawa moves north into Haro Strait

Wed 1/13/16 10:00 PST: Ottawa enters U.S. waters, proceeds north

Wed 1/13/16 10:45 PST: Intense sonar pings recorded on the Orcasound hydrophone

Wed 1/13/16 11:00 PST: Ottawa leaves U.S. waters near Turn Point, Stuart Island

Detailed Chronology (public Google spreadsheet):

Acoustic recordings and analysis

Sonar sequence repeated 4 times around 11:00

Below is a 2-minute recording of the Orcasound hydrophone (by another hydrophone network citizen scientist) at 11 a.m. on 1/13/16 containing 4 sonar ping sequences. Each sequence lasts 30 seconds and contains a series of complex rising tones followed by single 3.75 kHz tones at about 9 and 22 seconds into the sequence.

Audio Player

Spectrogram of a sonar sequence that repeated 4 times around 11 a.m.

Spectrogram showing the detailed pattern of sounds during a single 30-second sonar ping sequence.

Individual sonar ping at 10:55

Recorded and provided by another hydrophone network citizen scientist:

Audio Player

Spectrogram of a single ping on the Orcasound hydrophone at 10:55 a.m.

Individual sonar ping at 11:14

Recorded and provided by another hydrophone network citizen scientist:

Spectrogram of 0.5 second sonar pings at 3.25, 6.5, and 9.75 kHz recorded on the Orcasound hydrophone.

Comparison with SQS-53C sonar pings from 2003 Shoup event

Audio Player

Spectrogram of a single ping from the SQS-53C sonar during the 2003 Shoup incident.

Ship tracks and descriptions

The Canadian frigate Ottawa was observed in Haro Strait at the time of the sonar pings. If the time of the recordings and AIS locations are accurate, then the Ottawa was approximately 8-16 km north of Lime Kiln and Orcasound when the sonar sounds were recorded at those hydrophone locations.

AIS track of the Ottawa on 1/11 to 1/12.

AIS track of the Ottawa on 1/13.

AIS track of the Ottawa on 1/14.

Alternative Ottawa track map

The Canadian Orca class patrol vessel, Caribou 57, was also active and tracked on AIS. From Tuesday 1/12 noon through 1/13 it was patrolling withing the southern Gulf Islands.

Track of the patrol vessel Caribou 57 on 1/12-13.

Possible US Naval ships in/outbound from Everett on 1/13/2016 (Skunk Bay web cam):

Read More

I’m giving a talk on our recent paper (PeerJ Preprint) at the Green Tech Conference in Seattle today. Here is the agenda and my presentation:

And some notes I took during the 2-day conference in downtown Seattle.

Introduction

Green Marine is a non-profit based in Quebec, Canada, that certifies environmentally sustainability in the shipping industry. The initiative has a growing number of Canadian and U.S. ports [Seattle, Long Beach, New Orleans] and has 50 supporters (NGOs [including Seattle-based Puget Sound Clean Air Agency, Seattle Aquarium]. The number of participating organizations is growing (about 66% increase between 2013 and 2014). Green

Panel presentations and discussion

SUSTAINABILITY AT WORK IN MARINE TRANSPORTATION MADISON

- Linda Styrk, Managing Director, Seaport Division, Port of Seattle

- Stephen Edwards, CEO, GCT Global Container Terminals Inc.

- Dennis McLerran, Administrator, U.S. EPA Region 10

Linda:

The Century Agenda is the Port of Seattle’s 100-year vision: to be the cleanest, greenest port in North America. The Green Marine certification program emerged as the best way to progress environmentally. Stefanie Jones Stephens is Environmental Manager guides performance in different Green Marine metrics.

One practical example of the utility of the certification metrics is comparison with other ports and standards. The Port was surprised to score low in the in-air noise metric because few complaints had been received (possibly due to their proactive outreach). Quantitative comparison made it clear that an improvement could be made.

She showed videos of run-off filtering tanks (Harbor Island) and experimental above-ground gardens (“SplashBoxes” in areas where digging isn’t possible) for decreasing water pollution. In a project managed by GeAlogicA and funded by the Seattle Foundation, Capital Industry built rolling containers that held volcanic soil and plants. Port developed grant program (~$30,000-50,000 assistance to each participating truck/owner) that helped replace 500 trucks to reduce pollution during the 2000 truck trips per day.

Overarching thought is that the marine industry is very innovative, but perhaps too low-profile about it’s environmental advances. The Port of Seattle has many other green innovations (biodiesel, stack-scrubbers, …), but too few members of the public know about them.

Stephen

Container terminals (warehouse w/o roof!) are a distinct operation (e.g. from bulk facilities). GCT is based in Vancouver owned by a pension fund in Canada with U.S. terminals in New York and Bayonne. We consider ourselves a technological leader that serves 19 out of 20 global container shipping companies.

We didn’t know how we compared with other organizations in our industry. Green Marine was chosen because its metrics are driven by the participating organizations, not our customers.

There is an industry shift to larger vessels. Same number of ships, less weekly trips, and fewer companies. TEU has nearly doubled in 10 years (~2003-2013). Europe and Asia are seeing up to 20,000 TEU ships now…

Vessel sharing agreements group shipping companies (e.g. Maersk) into only 4 “customers.” North American Emissions Control Act caused higher costs in coastal waters (and therefore quicker turn-arounds): cleaner burning fuel costs 600$/ton vs $400/ton in the open ocean. These changes motivate investments in ship-terminal-truck semi-automation, scheduling, worker safety, and other logistics (e.g. no idling during waits).

Dennis (used to work for Puget Sound Clean Air Agency)

EPA has worked with 159 countries and the IMO to develop a uniform fuel requirement through the North America “ECA” (pronounced “Eek-uh” = Emissions Control Act requires large vessels to use cleaner fuel within 200 nautical miles of the coast). This rule prevents 31,000 premature deaths, 1.4 M loss work days, as well as lost school days (through the connection between ship exhaust and human health).

EPA is committed to working with the industry to find innovations that benefit the environment as well as the bottom line. Some examples of mutually-beneficial partnerships with industry. EPA worked with Tacoma-based Tote (RoRo line) is converting ships to burn (non-distiallate) cleaner fuels or LNG, which in the long-term will reduce cost of consumer goods in Alaska. Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA funding, RFP due June 15) has reduced pollution while returning value to the U.S. Government (usually through reduced human health costs). The SmartWay programs helps partners move more goods for reduced cost, in part by building off EPA’s brand equity.

EPA is developing a national port initiative, building off experience and leadership (of CA Ports). The key is for Ports to realize that they are stronger when both providing services to their customers and keeping their local communities and workers healthy.

10:30 session

TECHNOLOGY GEARED TOWARDS REGULATORY COMPLIANCE: LESSONS LEARNED

4 talks:

- Emissions scrubbers on the Algoma Equinox class vessels (Mira Hube)

- These ships are more fuel efficient and have reduced water use and noise pollution.

- We operate in emissions control area 100% of the time, so needed to reduce sulfur emissions (and NOx and particulates)

- LNG was an options, but there is a lack of LNG infrastructure in the Great Lakes

- EGCS

- Overview of exhaust gas cleaning system (EGCS)

- Manufactured by Clean Marine (Norway)

- Closed-loop, fresh water, NaOH scrubber

- Base neutralizes acidic emission components;effluent is treated onboard, then discharged

- CSL’s Experience with Ballast Water Management Systems (BWMS) (Yousef El Bagoury; and Kevin Reynolds from Glosten Associates)

- How do you choose a BWMS?

- 70+ on market; 32 IMO-approved; 16 have USCG temporary approval…

- Glosten did early BW installations in 2006, so helped evaluate options

- Glosten worked with CSL to 3D laser scan possible sites in CSL ships

- How to fit (massive) pumps (2k m^3/hr!); heaters; hydrogen vents; filters?

- 3D models and equipment size guided plans for shipyard installation

- Lessons learned

- Lots of (EPA/USCG) paperwork involved in permits and Class approvals

- Site supervision and crew training are critical

- Clean ballast tanks prior to commission (ours had mud that clogged filters)

- Preparing for USCG approval (testing late summer, 2015)

- Other ships getting 3D scans by Glosten

- Saga Forest Carriers – Ballast Water Treatment (BWT) Case Study (Birgir Nilsen)

- Optimarin started as ballast water treatment company in 1990s.

- 225 systems at sea; 50 are in use (on bulk carriers, Naval vessels…); medium scale — up to 3000 m^3/hr (largest are 7000 m^3/hr, e.g. in cruise ships)

- Regulatory environment: IMO, but also USA (USGS National Invasive Species Act; EPA Clean Water Act; plus confusing State variants (e.g. CA, Great Lakes))

- Pre-market conditions: customer buys equipment and intallation through “type approval certificates” (which should specify limits, like UV transmission and/or temp/salinity…)

- Basic system filters first and then disinfects with UV light (up to 35 kW from single lamp!)

- Sage Forrest Carriers (Optimarin customer)

- Open hatch mostly in paper pulp trade

- 1-2 km^3/hr ballast flows

- 3D scans (through Goltens sub-contract) of 24 ships (4 different ship designs)

- Little to no space: used part of ballast tank for equipment!

- System successful, but key is user training and operation manual (via officer conferences)

- Membrane Scrubber Technology for SOx Removal from Engine Exhaust (Gerry Carter & Edoardo Panziera)

- Wet scrubbers (dry scrubbers are used on land, but takes too long to warm up/down & maintain)

- All designs use combinations of sprayers and filters and (Achilles heel) water treatment systems

- Ionada innovation is a ceramic membrane separation technology

- Provides surface area for the chemical reactions (resulting in a clean crystal)

- But without mixing with the exhaust gases

- No PAH wastewater treatment!

- Potassium carbonate is less toxic than NaOH; reacts with SOx to from K2CO3 (a fertilizer).

- $14 to purchase KCO3; $14 from sale of fertilizer!

1330 session

CORPORATE ENVIRONMENTAL LEADERSHIP: INSPIRING INITIATIVES FOR THE INDUSTRY

Cooperation between NGOs and Industry to Define Sustainable Development in the Canadian Arctic

Andrew Dumbrille, WWF Canada & Marc Gagnon, Fednav

- FedNav (Marc)

- Canada’s largest dry cargo shipping group

- 1/3 grain, 12% steel, 14% alumina, 17% industrial mineral

- 80 ships: 59 operating, mostly handysize (Lakers), but more and more supramax and ultramax ships

- 24 ships on order, growth in part developing Arctic (Baffinland iron ore; Red Dog AK zinc/lead)

- Has environmental policy

- Working with WWF since 2011 (Marc)

- chosen due to being leader in industry, only company in Arctic during winter

- shared vision signed 2013

- What does it take to work with an NGO? Patience!

- Shared goals: environmental; economic; polar guidelines

- Completed “Best Practices in the Arctic” document

- Challenges: goals are different! Different positions on Arctic shipping (LNG only initiative is economic folly). Other WWF partnerships are sometimes in conflict with FedNav collaboration.

- WWF (Andrew)

- 5M members, 5000 staff, 500 million raised

- Hudson Strait: Reducing shipping impacts & risks (May 2015 contract report by Vard Marine, funded by FedNav)

- Key recommendation was a Polar Shipping Operating Manual (e.g. marine mammal behavior, set-backs, etc.)

Radical Improvements in Vessel Efficiency

Lee Kindberg, Maersk Line (co-chairing EPA Clean Cargo working group)

- Maersk enables trade with benefits and costs to the planet and humanity.

- 90% of all goods transported globally are carried by ship

- Ocean shipping 4% of global emissions (though NASA map still shows an impact)

- Since 2007, Maersk has been able to grow containers shipped by 40% while lowering CO2 emissions by 25%

- Energy efficiency makes good business sense.

- Using Clean Cargo Working Group metric, mean CO2/TEU/km, levels fell from 70-45% between 2008 and 2013 through new vessels, eco-retrofitting old vessels, “smart steaming” and network design (which ports of call, scheduling, personnel efficiency competitions)

- 2020 goal is 60% reduction

- Voyage Efficiency Systems (communications between leading and following ships) has evolved to Global Voyage Center (in India staffed 24/7 by 10 masters & 10 chief engineers)

- Terminal Efficiency Project: minimize harbor time to reduce local emissions, then slow steam later to regain coastal fuel losses

- New ships higher efficiency and have enormous economies of scale (e.g. Mary Maersk carries ~17.6 kTEU at 2,200 miles/gallon/ton)

- Of three new classes, biggest is Triple E: 18 kTEU, 50% more efficient (in part through waste-heat recovery systems)

- Retrofit options: new bulbous bow (“nose job” helps when vessels that used to run 22-24 knots are running at 16-18), prop, propeller boss cap fin, engine de-rating, fuel flow meters.

- Propeller optimization reduces cavitation

- Committed to $1 billion over 5 years for retrofitting 100 of owned vessels

- Reducing speed to <10 knots in Santa Barbara channel when whales are present… also have reduced speed on Atlantic seaboard (to protect Right whales?)

- Big shippers have played a role in motivating lower carbon shipping initiatives, but so have our core values… as have the economics of increased fuel efficiency in an era of expensive fuel.

ECHO Program: Collaborating to Manage Potential Threats to At-Risk Whales from Commercial Vessels

Carrie Brown & Orla Robinson, Port Metro Vancouver (Environmental Programs Department)

- Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation Program

- Mandate under Canada Marine Act: facilitate trade but in ways that are safe for the environment

- Initiated due to DFO status of species at risk and projected shipping growth

- History

- 2014-15 planning and launch

- 2016-17 development of target and implementing mitigation

- 2017 manage adaptively to reduce threats over time

- Advisory Working Group

- Acoustic Technical Committee: DFO, JASCO, NOAA, ONC, Robert Allan Naval Architects, SMRU, Transport Canada, UBC, U St. Andrews, Vancouver Aquarium, WA State Ferries

- Work plan: acoustic disturbance, physical disturbance, environmental contaminants; timely as in the last month we had a fuel spill in English Bay and a fin whale on a cruise ship bow…

- Acoustic Disturbance focus areas: will include vessel noise “weigh station,” hull cleaning

- Mitigation prospects: green tech, operational management options, criteria for Green Marine performance indicators (ultimately adding noise to air quality EcoAction program)

- Physical disturbance: working with DFO to survey and assess strike risk assessment; whale sighting and notification system; west coast mariner’s guide…

- Environmental contaminants: baseline sampling sediments and mussels, esp during hull cleaning

15:30 session

EMERGING ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES: AN INTRODUCTION TO UNDERWATER NOISE

Whales in an Ocean of Noise: How Manmade Sounds Impact Marine Life

(Kathy Heise, Vancouver Aquarium)

Early hydrophone work was from lighthouse, small boats, and included interest in Pacific White-sided Dolphins.

Shipping industry should keep in mind role of ship noise in cumulative acoustic impacts on all sound-using marine organisms (with other major sources being pile driving, seismic surveys, and military sonar).

Change is beginning: 2009 letter to Obama; IMO voluntary guidelines for vessel equipment and design (2014); EU Marine Strategy Framework. Good news is that practical solutions are at hand. It may be more expensive initially, but can save money in the long run.

Ship Noise in an Urban Estuary Extends to Frequencies Used by Endangered Killer Whales

(Scott Veirs, Beam Reach Marine Science)

Control and Measurement of Underwater Ship Noise

(Michael Bahtiarian, Noise Control Engineering)

- Ship noise vs shipping noise

- Analogy with aircraft and airports, but aircraft have a service life of 5 years while ships have one of 20-30 years, so quieting may be slower than what occurred in planes in the 1960s and 1970s.

- Research and fisheries have much of the quieting technology (not just the Navies)

- Vessel noise sources: cavitation, machinery,…

- Ship Noise Analysis Software helps establish a baseline and then assess improvements

- Mitigation technologies: insulation; vibration isolation; damping (spray-on and tile versions; from military innovations); floating floors/rooms; bow thruster and HVAC treatments

- Existing benchmarks

- International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (1995) ICES/CRR-209

- applies to fisheries and research vessels

- Followed by Europeans since 1995

- DNV, Silent class, 2010

- various “notations” (grades)

- Notations depend on class

- Measurement standards

- ANSI/ASA S12.64: Established 2009, first standard for UWRN

- Meeting next week to finalize ISO 17208-1: Precision method for deep water

- General methodology (figures from ANSI/ASA S12.64-2009)

- Facilities for UWRN measurements (can be provided to private industry by Navies)

- SEAFAC (Ketchikan, AK)

- Dabob Bay (Seattle, WA)

- San Clement Island (San Diego, CA)

- Florida

- Halifax?

- Noise Control Engineering uses BAMS (Buoy Acoustic Monitoring System)

- UWRN Design Guidance

- SNAME T&R Bulletin, 3-37, “Design Guide for Shipboard Airborne Noise Control,” 1983 (Supl 2000)

- JIP/OGP Report

- SNAME 6-2, MVEP GM-1, Ocean Health and Aquatic Life

- BOEM Report 2014-061

- Pending IMO Guide “Guidelines for the reduction of underwater noise for commercial shipping (estimated to be issued by 2016); a bit of a compromise of US, China, Europe, and (opposing) flag nations like Vanatu

Read More

Thanks to Professor Rick Keil and his UW Oceanography 409 class on Marine Pollution, I had a chance to go back through the data archives and review the research progress made over the last decade by Beam Reach students and faculty. Below is the talk I’m giving today in Rick’s class to wrap up their study of underwater noise pollution in the marine environment.

Read More

Thursday, 5/1/2014

8:30

Parker MacCready (with Matthew Alford)

Observations of flow and mixing in Juan de Fuca Canyon

Pacific water on the continental shelf exerts strong control over Salish Sea productivity, hyposia, and acidification. It is the most important source of nutrients for Puget Sound by a couple orders of magnitude.

The problem is that the Pacific water properties vary strongly with depth. There’s high oxygen water near the surface (DO as high as 110 near 150m) and low oxygen water below (DO ~50 at 800m).

The water enters the Strait of Juan de Fuca via the Juan de Fuca canyon, an understudied region

(see Glenn Cannon, 1972) that cuts across the continental shelf. It’s deep enough relative to the shelf that the inflow can move up the canyon (moving east-northeastward at about 40 cm/s, independent of the tidal state) underneath the surface current on the shelf (typically southeastward flow).

The along-canyon flow gets up to 75 cm/s. As it moves over sills, internal lee waves form that have amplitudes of up to 80m.

ROM model runs show inflow across shelf is primarily via the canyon:

Richard Feely

The impacts of upwelling ocean acidification and respiration on aragonite saturation along the WA continental margin

Due to upwelling we are seeing pH conditions that won’t be seen the global surface ocean until the end of this century. The upwelling low O2 water also has high pCO2, low aragonite saturation state, low pH for water >80m depth.

Feely described a new model that can predict water properties 6 months in advance, a tool which could be very valuable to Salish Sea shelfish growers.

Local respiration uses up the (already low) oxygen and increase pH as the water flows in. This can result in anoxic events downstream.

What forces the inflow? Wind from the north!

Ref: Alford and MacCready (2014) Flow and mixing in Juan de Fuca Canyon, Washington. Geophysical Research Letters, 41.

Rob Fatland is talking later about using ROM to visualize the flow of water across the shelf, primarily via the canyon.

The transport observed is about equivalent to the Amazon River, 200,000 m^3/s, easily enough for the Salish Sea “estuarine circulation” about 30,000 m^3/s.

9:00

Christie McMillin (Marine Education and Research Society mersociety.org)

Anthropogenic threats to humpback whales in the Salish Sea: insights from northeastern Vancouver Island

2012 Juvenile humpback stranded (long line entanglement)

2013 photographs (by Mark) indicate that it was a high recent year (along with 2011; nice graph)

1985 Merilees documented two periods of whaling in the Strait of Georgia in the late 1800s. Place names like Blubber Bay reflect this history.

Northeast Vancouver Island had whaling as late as 1968 and many humpbacks were taken in the 1950s on the west side of Vancouver Island.

Since 2006 they have documented 8 vessel strike injuries. Since 2009 there have been 5 witnessed cases of entanglement in prawn gear (3), crab gear (1), and seine net (1). In 4 of 5 entanglements, the whale was disentangled.

We can estimate total (non- + witnessed) entanglements by photographing leading edge of tail stock. This method suggests that 9 additional entanglements have occurred in our study area.

There are concentrations of humpback distributions northeast of Hanson Island, while much lower densities occur in Johnstone Strait (particularly SE of Hanson). This observation informed new signs warning vessel operators of the high density areas.

Is you witness entanglement or ship strike, DFO has a hotline, but with a VHF you can call the Coast Guard.

9:15

Jared Towers (DFO/Marine Education and Research Society)

New insights into seasonal foraging ranges and migrations of minke whales from the Salish Sea and coastal British Columbia

Minkes do breach!

Highest distributions are on west side of San Juan Island, the banks, and Race Rocks, as well as North Vancouver Island. Lower densities further north and on the outer west coast of Vancouver Island. Despite effort, none were observed off Nanaimo area in the Strait of Georgia.

Strong seasonal distribution, peaking in July. No sighting during ~Oct-Mar.

Previous research: Dorsey et al., 1990. Rep Int. Whal. Commn. Special Issue 12.

Intra-annual movements occur spring-to-summer and summer-to-fall suggest migration. Ecological markers (e.g. scars, swordfish beaks embedded in blubber, diatom coatings or barnacles, cookie cutter shark bites, lamprey scars, Xenobalanus colonizing trailing edge of fins [occurs in tropical east Pacific]). Ref: Towers et al. (in press) Cetacean Research & Management (?)

Prey seems to be juvenile herring and juvenile and adult sand lance. We observe bait balls in the NVI and they may occur in the SJI area, too.

9:30

Marla Holt (recording in .mp3 format)

Using acoustic recording tags to investigate anthropogenic sound exposure and effects on behavior in endangered killer whales

Goals: quantify noise that individual SRKWs experience; determine relationship between vessels and their attibutes and received noise levels (RL); investigate kw acoustic and movement behavior during foraging.

Digital Acoustic Recording Tags (DTAGs) have two hydrophones (one for background noises, one for KW signals), as well as orientation and movement sensors. We have 3 field seasons of data so far (Sep 2010 [before 2011 vessel distance increase from 100-200 yards], Jun 2011, Sep 2012) and plan more deployments this year. 23 tags on all three pods.

Animation of a 7-hour tag in Haro Strait SE down Haro canyon, across to Salmon bank, south along its western edge, and then across to ENE Hein bank.

Received levels: RMS averaged over 1 sec in dB re 1 uPa, 1-40kHz band. 2768 measurements of RL (w/o flow noise or whale signals), min 88 dB (3 vessels 2 stationary 1 slow (0-2) kts; Max 141 dB large fast vessel (ferry passing less than 300m from whale!) Julian Houghton’s theses working up predicted noise levels and finding speed and (size, distance??) are most important factors in RL.

Variations in pitch and roll may indicate foraging changes, but few prey samples have been acquired during focal follows with DTAG deployments.

9:45

M. Palomares

The Salish Sea ecosystem in FishBase and SeaLifeBase

We have documented the iodiverstiy of Salish Sea in two databases:

- fishbase.ca

- sealifebase.ca

~82 references used to assign 2,280 species to for ecosystems

Gatydos et al. 2008, 2011; Cowles 2005

Fish completed; birds and marine mammals need work; many invertebrates.

The full fish list is at — http://www.fishbase.ca/trophiceco/FishEcoList.php?ve_code=1067

These data (particularly the trophic pyramid, as well as the “1-click ecosystem routine’) should help researches build ecosystem models. 68% of fish species have biological data in FishBase. There are at least 12 species that are commercially important that don’t have life history data, so they could not be included in the reslience estimations.

There are efforts to cross-reference with the barcode of life movement.

10:45

I. Vilchis

Common risks among declining marine predators suggest ecosystem change

39 taxa of wintering birds in 8 Salish regions and three depth categories

The birds most likely to undergo a decline (based on their model) were the diving birds without local breeding colonies. Across categories, decline probabilities are higher in the birds that eat fish (vs non-fish eaters).

Why are diving birds over-wintering less in the Salish Sea? We suspect that this is because there have been long-term decreases in the forage fish abundance in the Salish Sea. (Some studies have shown concomitant increases in over-wintering populations in California.)

One idea is that the specific power required to maintain a certain air speed is much higher for diving birds. (Nice use of archive.org videos embedded in slide to show difference in flapping frequency in puffins vs frigates.)

Conclusion: Salish Sea birds are shifting wintering feeding ground as a result of lack of prey.

11:00

P. Arcese

A century of change in trophic feeding level in diet specialist marine birds of the Salish Sea

Western Grebes have declined by 97% in 40 years here and increased 230% in southern CA. Pacific sardines were extremely abundant before being overfished, but the have come back dramatically since the 1980s (Ref Hill, 2010?)

Murrelets in BC have gone from ~500k to 50k population and were studied isotopically using historic samples (feathers formed early in year [condition prior to breeding]) from museums around the world, including bird collected by Vancouver (Norris et al. 2007, Journal of Applied Ecology). The dN15 decline they observe suggests a decrease in trophic level of the murrelet diet from mainly fish to mainly euphausids. Fecundity vs bird count data, suggest that forage fish abundance may be limiting reproductive rates.

Even glaucus winged gulls are in decline. Mondarte populations down from ~3000 to ~900. Average age size is also decreasing (Blight, 2011).  The isotopic decline in gull feathers is consistent with the murrelets.

The western grebe is a herring specialist, but isotopic data from grebes have maintained diet (on herring) but most have left the Salish Sea.

11:15

Jessica Lundin

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the Puget Sound ecosystem: An evaluation of POPs in fecal samples of Southern Resident killer whales

247 samples in final analysis, including toxicants, hormones, and genotyping

Toxicant results: dried fecal samples vs blubber samples from same whale (30 whales) show strong corrleation; unprocessed (undried) fecal samples vs blubber also highly correlated.

- Higher ratios of ppDDE/sum(4PCB) are highest in L, and secondarily K pods relative to J pod

- Females with >1 calf have lower 2-5x toxicant loads than juveniles, males, and post-reproductive females (who have the highest values)

Graphs of Columbia and Fraser Chinook returns show a ~2 month gap during which there is evidence that toxicant are being mobilized from their lipid stocks.

Ratio of sum(PBDE)/ppDDE shows an increasing trend (2010-2013) suggesting that PBDEs are bioaccumulating.

Next steps are to look at relationships between toxicants and hormone. A pregnancy test has been developed which could be used to assess reproductive success (and hypothetically may be influenced by toxicants).

11:30

30 minute discussion (.mp3 format) at end of Session on “Marine birds and mammals of the Salish Sea: identifying patterns and causes of change – II”

Lunchtime presentations:

Friday May 2, 2014

9:30

Natalie Hamel

The 2013 State of the Sound Status of the ecosystem

PSEMP = Puget Sound Environmental Monitoring Program works with partners to monitor and report conditions and assess restoration efforts. The Puget Sound Vital signs are one tool used to assess ecosystem conditions. Such assessments go back many years (e.g. “Puget Sound’s Health” 1998) and should be continued.

Vital Sign characteristics:

- The “wheel” is fundamentally a communication device, designed for a wide audience (simple, distilled, appealing)

- Indicators founded in science, prioritizing: good surrogates for ecosystem conditions; available historic data; quick response to ecosystem change (including restoration efforts)

- Connections to recovery goals (with both baselines and targets)

Graphs and interpretation of trends in them are simplified into a simple progress scale (with baseline at center, target delineated, and % change indicated by a marker of current conditions.

As of the end of 2013, a few vital signs showed progress, some have lost ground (e.g. orcas), and many that are far from the 2020 targets. One concern is a need for more short-term, responsive indicators.

9:45

Kathryn Boyd

2013 State of the Sound: Accountability and funding of Puget Sound recovery

As of Sep 2013, 68% of the 2012 near term actions were on plan or complete, 12% were off-plan, 7% had serious constraints, and 12% were not started.  The primary cause of delays was lack of funding. In both 2012 and 2013 there were funding gaps of 100’s of millions of dollars.

The Action Agenda Report Card gets updated quarterly and automatically as partners report in. These online data show that the number of complete Near Term Actions (NTAs) is rising overall (2012Q3-2014Q1). Shellfish actions are a good example of steady progress to completion.

10:30

Brian Sackman

Eyes Over Puget Sound: Producing validated satellite products to support rapid water quality

RDI workhorse (300 kHz ADCP) on WA State ferries

Victoria Clipper samples every 5 secs (~100m), 80 mile transect 4 x /day, (T,S,Chl)

MERIS ocean color satellite (2000-2012) combined with others, e.g. LandSat (2000-present, 30-500m resolution nearshore; >1km coastal/offshore)

To ground-truth, they used partial least squares regression (commonly used in chemometrics, bioinformatics when many parameters are available and correlated). Working towards an operational workflow.

10:47

Amy Merten

Open source mapping to improve data sharing: Environmental response management application

Web-based mapping tool — Environmental response management application (ERMA) — aiming to make data sharing between agencies, coordinated through UW Tacomea’s Puget Sound Institute. Now trying to complete after starting before Deep Water Horizon spill distracted. Real-time data (e.g. from AIS, NOAA weather buoys, NANOOS), forecast data (weather?), and base maps and database (e.g. Marine Protected Area portal, Burke Herpetology collection, Encyclopedia of Puget Sound, NatureServe?, Audubon data on Canadian watersheds and bird distributions) goes to ERMA Data Center and is accessible from oil spill response Command Center.

Whale telemetry data can be imported and animated. Satellite tag example.

Upcoming events: August 2014 drill; CANUSPAC.

11:03

Rob Fatland (Microsoft Research)

Ebb and Flow: What we learn from visible circulation patterns in the Salish

All technological problems are solvable. You just need to find the write person.

Geophysicist (glacialogist turned oceanographer). Microsoft offering 1 free year Azure cloud computing, but the challenge is finding the right collaborators to help manage data. Cyberinfracture involves registering and communicating about data sets. Machine learning is the likely way to distill big data from the growing cyberinfrastructure.

Worldwide telescope is the core of http://layerscape.org

12:30

Wade Davis, UBC

The critical importance of preserving ecosystems for current and future generations & the significance of ancient wisdom

Audio recording ( .mp3 |.ogg | .flac )

1:30

McKechnie, I.

The Herring School: Long-term perspectives on herring in the Salish Sea and beyond

At 179 sites along BC coast and in WA (inland) herring was the major commonality (all but 2 sites on N Coast) and was extremely prevalent in the Salish Sea. % of herring relative to other fish (based on bone archealogy) varied from 80% in northern Strait of Georgia to 20% in Puget Sound. Distance from herring bone sites to existing herring spawning sites is <~2km.

Visible foodstuffs in a drawing of part of Chief Maquinna’s house include 2675 herring/anchovy, 20 flatfish, 10 greenling/cod/hake!

pacificherring.org was launched this morning. A really cool feature of it is the 12,000 year timeline of herring on the coast of Alaska, British Columbia and Washington.

2:15

T. Francis

Can we have our herring and eat our salmon too? A qualitative approach to modeling trade-offs in the Puget Sound foodweb

Foodweb figure coming…

2:30

J(oan?) Drinkwin (Northwest Straits Derelict Fishing Gear — winner of the 2014 Salish Sea Science Prize! )

Observed impacts of derelict fishing nets on rocky reef habitats and associated species in Puget Sound

PS has lots of derelict fishing nets because of abundant rocky outcrops and long-history of salmon fishing. Nets located with side-scan sonar and reports from divers, etc. All material removed by hand, not grapnel. 4467 gillnets removed (95% of those located), 168 purse seine (10?%). 672 acres of habitat restored as of March 31, 2014. %5 of fish found dead in nets are rockfish (including one canary rockfish).

Next steps are to continue removal, including with expanded fleet.  Need funding to go deeper than 105′.

Annual net loss is 10-30 nets and our new program aims to keep new nets from accumulating in the environment, including education and tools to increase (often mandatory) reporting by fishers. Of 24 reports in pilot program, 10 were removed, 7 had unknown location, 2 not found, 4 not derelict fishing gear, 1 in Columbia River.

Read More

Sponsored by the Puget Sound Partnership and organized by Orca Network, the Salish Sea Association of Marine Naturalists, and The Whale Museum, this workshop preceded the 2014 Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference.

Daniel Schindler, UW

The “Effects of salmon fisheries on SRKW” report

12:09 Starts with introduction of the science panel members

12:12 We were charged with evaluating the BiOp’s “chain of logic linking Chinook salmon fisheries to population dynamics of SRKW”

Population decline in both NRKW and SRKW was coordinated in late 1990s.

We were blown away by the quality of SRKW demographic data. This is probably one of the best-studied wildlife populations in the world.

Eric Ward estimated growth rate (lambda) as 0.99-1.04 (mean ~1.017, or ~1.7% exponential growth) for J/K pods and 0.985-1.035 (mean ~1.01, or ~1% exponential growth). The overall SRKW rate of 0.71% per year might increase to ~1%), but fisheries management changes are unlikely to raise the growth rate to the recovery goal.

There are 1000s of papers about Chinook salmon, but less is know about Chinook topics relevant to SRKWs. Listed 3 shortcomings.

Kope and Parken summarized Chinook trends for specific stocks important to SRKW. Coastwide there has been a modest decrease in recent pre-harvest Chinook abundance. There isn’t much room to lower commercial fishing in a meaningful way (e.g. decrease harvest of 20%).

Correlations between SRKW vital rates and Chinook abundance depends on abundance measure chosen. Mortality of SRKW should scale non-linearly with salmon abundance, but the existing correlations are linear.

12:38 Questions

Bain: Why weren’t acoustics impacts of fishing vessels considered? A: I don’t know. Perhaps because available data did not include fishing boats.

Felleman: Were analyses done using only Columbia Chinook? A: No, but you should email Eric Ward about that. You should also be careful about interpreting correlations as causal relationships. If you look for correlations from 50 different salmon populations, you’ll find strong ones just through random chance.

12:50

Elizabeth Babcock, NOAA

The intersection of salmon and orca recovery

Focus is on Puget Sound stocks. Locally-developed recovery plans for Puget Sound Evolutionary Significant Unit (14 watersheds from Neah Bay to Point Roberts; 22 populations) reviewed in 2005, then adopted plan in 2007, and are now implementing with partners.

70% of our estuary habitat area in Puget Sound have been lost…

13:00

Lynne Barre, NOAA

13:10

Mike Ford, NOAA

Salmon recovery and SRKW status

Noren (2011) suggest SRKW metabolic demand is 12.6-15.1×10^6 kcal/day =~1000 Chinook salmon/day

Ward looked at all available Chinook time series and found many correlations, including between runs, but the strongest correlations were not with the Fraser nor the Columbia.

Interesting population projection figure from Ward (2013)

Post-workshops we have been looking at trends in other marine mammals: AK and NR KWs increasing, CA sea lions now ~6x 1975 levels, harbor seals 6-8x…

Overview of salmon status

- Historic Chinook salmon abundance figure (compiled Jim Myers, NWFSC): Biggest reductions were in Columbia (~-3-5x) and Central Valley (~-3-4x)

- Bonneville time series (1938-2014) shows abundance declines happened a long time ago (pre-dams!). 2014 levels approaching 1888 average levels!

- A lot of the historical losses are due to extirpations (Gustafson et al., 2007): biggest extinct populations were in Columbia above Grand Coulee and Snake

- Run timing changes: Columbia example — ~10x reduction in interior run (above Bonneville) from ~2.5 million to ~200k.

- Hatchery production rose from 1950 to peak in mid-80s and in 2000 was near 1970s levels (Naish et al. 2007)

- Puget Sound historical abundance is ~700k (based on cannery pack in 1908); current wild escapement is ~50k; hatcheries add ~300k.

Recovery activities

- Habitat: 31,000 projects completed at 51,000 locations throughout Pac NW. Over $1 billion spent on restoration to date.

- Hatcheries: overall reductions in hatchery releases in last few decades, and limiting genetic impacts on wild fish. One example of reductions to near zero is on OR coast…

- Harvest: easiest to change and responsive; examples of successful catch reductions are Hood Canal summer chum. Coastwide harvest % has decreased by ~factor of 2 over last 30 years

- Hydro: improved fish passage, predator control, spill, barging; dam removal on Elwha, Condit, Rogue, Sandy, Hood River

- Heat: potential effects of climate change mostly not great for salmon; summarized by Stoute et al. 2010 and Wainwright and Weitkamp in prep

Budget comparison

- Orca recovery spending: FY12 1.2M on science/research; ~300k on management/conservation

- Orca salmon spending: FY12 600M!! Columbia only is 450M!

1:40 break

David Troutt, Director of Nisqually Natural Resources (for 35 years) and Chair of SRC (=Salmon Recovery Counci)

WA State salmon recovery — How we work together

2:02

State broken into regions, each with their own recovery plans (developed through the “WA way” involving many stakeholders, endorsed by Feds). Go to RCO web site for more information.

Study completed in March 2011 estimated costs of all planned regional plans is ~$5.5 billion. Funds dispersed through Salmon Recovery Funding Boards established in 1999. Funds come from PCSRF and others… Note: it is a LOT cheaper to protect than to restore…

10% of Federal grants must be used for monitoring. Example: About 80% of Nisqually outgoing smolts remain in estuary; 20% seek pocket estuaries elsewhere, but we see almost no returns of fish using the latter strategy.

There is a problem with marine survival in Puget Sound. We see 95% mortality of tagged out-going smolts between the Nisqually and Port Angeles. We’re confident that the estuary is in much better shape and 77% of the mainstem is in permanent stewardship, but we’re not seeing any result in the numbers of returning adults!

2:15 Tribal perspectives

Story: a generation of Nisqually fishers have never caught a steelhead. Annual catches of ~2k by tribes and ~2k by recreational fisheries collapsed (in 1990s?) to total run of ~500, a condition which persists. The treaties have not been withheld (and the tribes have not “shot at y’all in a long time”).

We need to work together towards ecosystem restoration. The tribes are interested in actions related to all H’s. The tribes have been working with the State to adapt how we run hatcheries to support harvest, but also be consistent with recovery goals. The North of Falcon process is part art, part science, but it is transparent and it works.

Rich Osborne, North Pacific Coast Lead Entity Coordinator (WRIA 20)

WA Sustainable Salmon Partnership — Salmon recovery on the WA coast

2:25

What’s unique about the outer coast in terms of salmon restoration?

- All 5 salmon species and steel head; none are listed except Ozette sockeye.

- Large areas are encompassed within tribal lands, which allows alternative restoration strategies.

- Almost no people! Only 7000 people on coast with no residential areas

- Large portions of watersheds in National Park, other large areas in National Forests.

Formed a non-profit to raise money beyond the SRFB: the WA Coast Sustainable Salmon Foundation. WRIA 21 = Quinalt; WRIA 22&23 Grays Harbor; WRIA 24 Pacific County.

Example projects:

- Goodman Creek road decommissioning (4 miles of road and fill removed)

- Quinalt: old logging road and fish passage blockage removal — facilitated by ability for tribe to control local decisions.

- Grays Harbor: huge estuary Chehalis has spectrum of impacts (industrial, logging, headwaters in National Park), but again not many people

- Pacific County (Willapa Bay): huge estuary w/few people; mostly Weyerhauser timber operations between pristine upper watersheds and the ocean.

28 Chinook stocks returning only 30-40,000, but could be 100s of 1000s…

An additional 12 million hatchery fish released from coastal watersheds per year

Salmon stronghold study areas (circa 2006)

Jeannette Dormer, Puget Sound Partnership

Salmon Recovery in Puget Sound

2:45

In contrast, there are 4.1 million people in the Puget Sound region: 12 counties, 20 large cities, 100 cities total, 17 treaty tribes, many NGOs; 15 lead entities; Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Council (not the Partnership) is policy body to oversee implementation of the PS salmon recovery plan.

6 salmonid species, 3 listed under ESA (PS Chinook threatened in 1999, Hood Canal summer chum threatened in 1999, 2007 Puget Sound steelhead).

Salmon recovery success example: Puget Sound Acquisition & Restoration (PSAR) Fund. Regional priority list; increased from $15 million to $70 million appropriated for 2013-2015 biennium

- 100s of acres of estuary restoration in Snohomish and Skagit rivers

- Elwha dry lake bed reforesting

- 3+ acres eel grass on Bainbridge

- Seahurst seawall removal and restoration

Intersection with orca…

3:05

Jacque White, Exec. Director of Long Live the Kings (used to work at P4PS and Nature Conservancy)

Salish Sea marine survival project

Many partners supporting the coordinating organizations — Long Live the Kings in U.S. and Pacific Salmon Foundation in Canada

“Puget Sound salmon are sick and we don’t know why…”

- Coho marine survival declined sharply in 1980s from ~3% to <~0.5% and has persisted, while during the same period (1974-2007) WA/BC coastal survival has been fluctuating around a mean of ~0.5%. There are similar trends for steelhead and Chinook.

- Declines in Fraser sockeye, steelhead, herring spawning areas, forage fishes, hake, lingcod

- Rises in Harbor seals, lags, temperatures, and human population

- Little effort to integrate research efforts

- Now seeing economic impacts on humans (sports fishing, tribes, First Nations)

Time line:

- 2007 State of the Salmon in 2007 focused on interactions of wild and hatchery salmon

- 2012 fall workshop led to idea of a transboundary project to increase survival in the Salish Sea, improve accuracy of adult return forecasting, and assess success (or failure) of existing salmon recovery efforts.

- 2014 Comprehensive planning

- 2015+ Implementation of research

Hypotheses (trying to identify factors that control salmon and steelhead survival that can be managed)

- Bottom-up processes (PDO, environment, forage fish changes to which salmonids haven’t been able to compensate)

- Top-down (predation…)

- Other factors (toxics, disease…)

Research activities

- Focus on juvenile fish

- Predation of seals on steelhead

3:45 break

Panel discussion (audio recording: .ogg [~68 Mb] | .mp3 [~34 Mb]; responses are hard to hear for some panelists who did not use microphones)

3:58 Begin

5:14 Final comments and next steps (also included in audio recordings)

Read More

The year 2013 was an exceptionally unusual one in the world of southern resident killer whales and Pacific salmon. Most noticeably, the southern residents returned to the Salish Sea later than normal, raising concerns among conservationists. Throughout the summer, researchers and whale watch operators noted that the whales were present less than normal and the duration of their visits to the Salish Sea were abbreviated.

Meanwhile, the Chinook salmon runs on the Fraser plummeted while 80-year record returns were counted on the Columbia at the Bonneville dam fish ladder. Combined with new evidence from satellite tags that the southern residents are focused on Columbia salmon during the spring months, the sighting patterns of 2013 may indicate a transition for the urban estuary known as the Salish Sea — from one with “resident” orcas to one with southern “transient” fish-eating orcas.

Killer whale trends

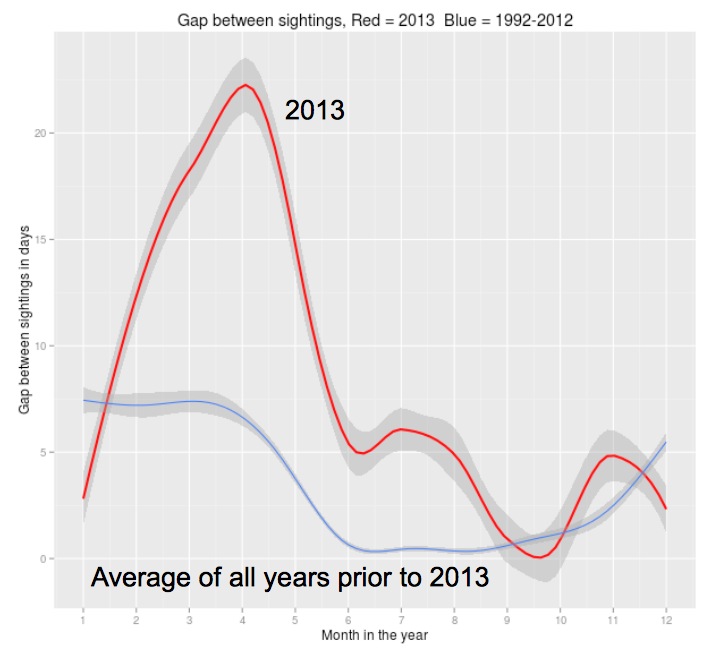

Based on data from the Orca Network sighting maps from the past decade (see figure below), records were set or tied in 2013 for the least number of days spent by southern residents in the historic core of their summer habitat (the west side of San Juan Island in Haro Strait). The SRKWs were seen only once in March and not at all in April. Even more shockingly, they showed up only 5 times in May (a record low) and were observed 15 times in June, a low level not seen since 2001.

The same data show downward trends in monthly sightings over the last decade. With the exception of a high in 2011, the March prevalence has been flat or decreasing. There are stronger, more continuous downward trends in April and May sightings.

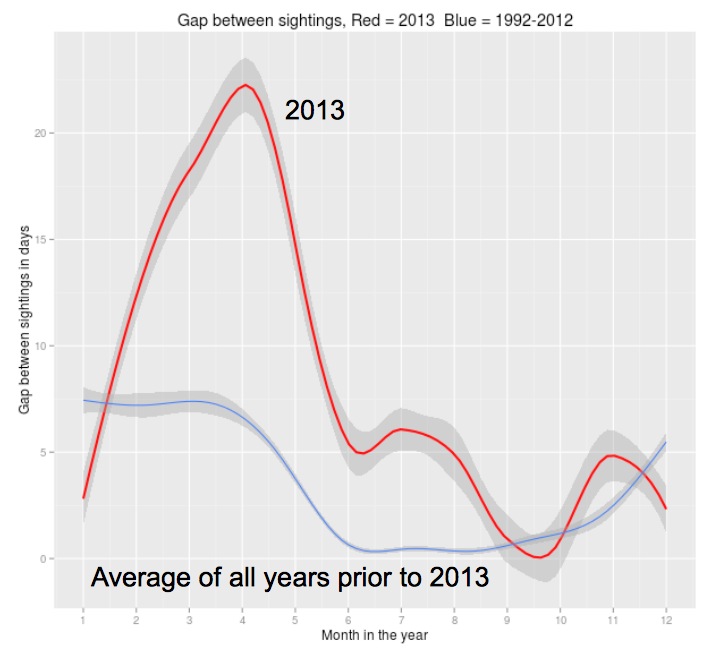

We used the OrcaMaster database maintained by The Whale Museum to look for trends in sighting “gaps” — the number of consecutive days between sightings of J pod members within the Salish Sea.  Val plotted running averages of 2013 gaps versus a historic average (1992-2012) and found that in the spring of 2013 sighting gaps were 2-5x longer than the average. Only during and after September of 2o13 did the gap return to a normal duration. (Maybe we should look at trends in Salish Sea chum run?)

Historic trends in J pod sighting gaps (Val Veirs, using R and ggplot)

Chinook trends

One way to characterize the foraging conditions the SRKWs experienced in 2013 within the Salish Sea and on the outer coast is to examine the Chinook salmon counts from the Fraser and Columbia rivers. The Albion test fishery on the Fraser provides a proxy for the abundance of Fraser Chinook, the primary prey of SRKWs in the Salish Sea from spring through the summer (Hanson, Baird, Ford, Hempelmann-Halos, Van Doornik, Candy, Emmons, Gregory Schorr, Brian Gisborne, Katherine Ayres, Samuel Wasser, Kelley Balcomb-Bartok, John Sneva and Michael Ford, 2010). The fish counts at the Bonneville dam on the Columbia are a proxy for the abundance of Chinook on the outer coast of Washington.

As marine naturalists like Jane Cogan and Monika Wieland have pointed out, 2013 was an exceptionally bad year for Fraser Chinook returns. The fish arrived late and the cumulative returns were well below this historic average and only slightly better than in the worse year on record, 2012. The highpoint of the 2013 run was the peak around the 3rd week of August that may also be related to a pulse of Chinook recorded in the first two weeks of July off southern Vancouver Island (in the Area 20 test catch fishery).

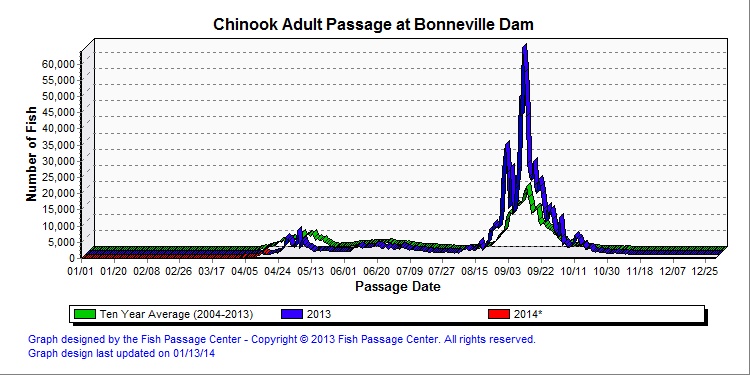

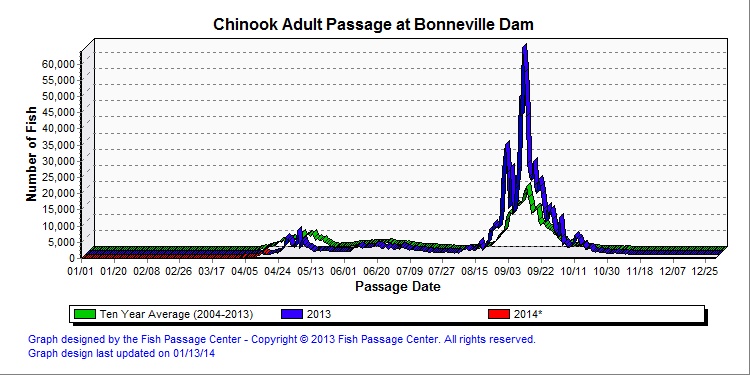

In contrast, adult and jack Chinook abundance in the Columbia River has been on the rise for the past couple decades, with 2013 standing out as a record-setting year for adult Chinook.

Daily Chinook counts at Bonneville show that while most of the record-setting abundance was due to the fall run, the spring run also had peaks well above the 10-year average.

Daily Chinook counts at Bonneville show that while most of the record-setting abundance was due to the fall run, the spring run also had peaks well above the 10-year average.

The spring run passed Bonneville from late April to late May, 2013. This timing is consistent with the timing of the spring Columbia Chinook run in 2012. Since Bonneville dam is about 200 km upstream from the river mouth and adult Chinook swim at about 0.5 m/s, we could expect that the returning Columbia Chinook were in the ocean at least until about a week before they reached Bonneville ( 200,000 m / 0.5 m/s = 400,000 seconds = ~5 days). So where were the southern residents in March and April of 2013, since they weren’t being sighted in the Salish Sea? We don’t know about J and L pods, but the satellite tag deployed on K25 indicates the likely position of K pod (up until April 4).

The answer is: during March, 2013, K25 was spending a lot of time going back and forth along the continental shelf of Washington (and to a lesser extent Oregon) with a track that centered on the mouth of the Columbia River.

We need to know more about when the returning Columbia fish are on the continental shelf and accessible to the southern resident killer whales. But these salmon trends from the region’s biggest rivers combined with migratory patterns of the orcas strongly suggest that the southern resident killer whales may be happy to move their “residence” to wherever the eating is best! Perhaps we are watching them become southern transient fish-eating killer whales?!

Anecdotal observations of orca-salmon interactions

When the fish-eaters were around during the summer of 2013, they displayed some unusually aggressive foraging. A (potential) prize Chinook salmon was taken off a derby fisherman’s line and became the focus of a KPLU radio story and an impressive photo of the one that was eaten away…

The part that didn’t get (taken) away. (credit: Kevin Klein)

This local predation event was a first for Washington State (as far as we know), though it was comparable to one by Alaskan fish-eating killer whales. In the video below, the Alaskan whales were foraging amongst fishing vessels and happened (probably visually) upon a large hooked Chinook. (Mute your speakers if you don’t want to hear angry and amazed fishermen cursing.)

Later in the summer of 2013, back in Washington, a whale watch captain obtained this video of southern resident killer whales pursuing a large (likely Chinook) salmon alongside the boat —

Could these uncommon foraging observations indicate that the southern residents were having a tough time finding enough to eat in the Salish Sea? We’d be interested in hearing from local fishers about how often they’ve had fish taken off their lines by Southern Residents. Monika assures us though that it is common to observe SRKWs pursuing salmon around and underneath whale watching boats, so maybe we should attribute the second video to more typical foraging and take it as evidence that orca-salmon interactions in the fall of 2013 were more typical than earlier in the year.

7919

{5THBC54C}

apa-no-doi-no-issue

default

ASC

no

5175

http://www.beamreach.org/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

Hanson, M. B., Baird, R. W., Ford, J. K. B., Hempelmann-Halos, J., Van Doornik, D., Candy, J., … Michael Ford. (2010). Species and stock identification of prey consumed by endangered southern resident killer whales in their summer range. Endangered Species Research, 11, 69–82.

Read More

Last June (2012) marine mammal researchers and stewards around the Pacific Northwest were surprised to learn of seismic research cruises that would use air guns to survey faults and crustal structure on the outer coast of Washington and Oregon. Our concern was that there would be inadequate mitigation of potential acoustic impacts on marine species (particularly southern resident killer whales). It all happened very fast and I never heard much about how it went… until now.

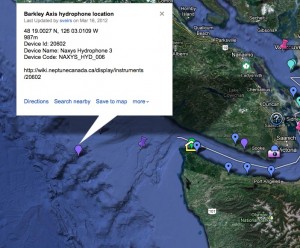

Thanks to John Dorocicz who has been logging acoustic highlights from one of the hydrophones maintained by NEPTUNE Canada near the head of Barkley Canyon, I just had the rare opportunity of hearing airgun blasts in the real ocean — complete with simultaneous vocalization of nearby dolphins. The date and time of the recording match up very well with a cruise track of the R/V Langseth, the research vessel from Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory.

Here’s where the Barkley Canyon hydrophone is located:

Here’s where marinetraffic.com AIS shows the Langseth was at 8:25 UTC on 2012-07-19, about 175 km south of the hydrophone.

And finally, here is a spectrogram of two seismic blasts recorded at 10:13 on the same day, along with sounds from (likely Pacific White-sided?) dolphins.

Listen to the recording and you’ll notice the low-frequency rumbles of the airgun blasts along with what seems like an increase in dolphin vocalizations (visible as wiggles at 4-6 kHz in the last fifth of the spectrogram). I wonder if these were the first two blasts the dolphins experienced. If so, then the suggestion (made by John initially) that the dolphins are responding to the blasts seems tenable. But were there many blasts before this recording was made? And why wouldn’t they react as much to the first blast in this recording as they seem to react to the second blast?

Regardless of the answers, it is exciting to hear what airguns sound like on Washington’s outer coast at a range of nearly 200 km. The number of marine animals exposed to the sounds of seismic exploration is staggering and begs the question: is the risk of interfering with so many oceanic lives worth knowing more about the subduction zone that may someday rock our west coast cities?

Read More

Live blog from the third and final workshop on “Evaluating the Effects of Salmon Fisheries on Southern Resident Killer Whales” that begins today (9/18/2012) in Seattle, WA.  The workshop runs Tuesday-Thursday (9/18-9/20). During this third step in the process NOAA initiated to manage chinook salmon with attention to southern resident recovery, a U.S.-Canada science panel will hear comments on their draft science plan along with new presentations of data and analysis that may improve the plan.

Exciting aspects of the workshop III agenda are presentations by Mike Ford on diet and distribution of SRKWs, Sandie O’Neill on contaminant and stable isotope insights, Sam Wasser on hormone analyses, John Durban on growth and body condition, and Dawn Noren about energy requirements.

Most presentations (will) include links to the slides (PDF or PPT) archived on the workshop web site. Select presentations also include a link to the audio recording of the presentation.

Day 1 (Tuesday, 9/18/2012, 8am-5pm)

8:16 Pat of WA Dept of Fish and Wildlife comments (mp3)

- Generally agree with draft report regarding the low impact of extant fisheries on killer whale recovery.

- But, in sections 5.2 and 5.3 the report mentions the distribution of “far north-migrating” Chinook stocks. Coded wire tag and genetic data from off WA coast show that many stocks are present, including: Sacramento and Northern Oregon coast. Columbia river summer chinook do sometimes wander into the Strait of Juan de Fuca or the San Juans.

- Need more data on winter distribution of SRKWs.

- There maybe thresholds effects, but they may be hard to detect.

- Eric Eisenhardt comments:

- SRKWs did go north of Vancouver island twice this summer, so that confirms they are foraging outside of Puget Sound and the Northwest Straits

- L-112 Victoria/Sooke had both Chinook salmon and halibut in her stomach.

8:36 John Carlisle of Alaska Department of Fish and Game comments (mp3)

- Growth rate criteria may not be the best metric for recovery. The growth rate will ultimately decrease as the population reaches carrying capacity. If you go to an abundance-based criterion, you’d conclude that the population is going to recover. Since the aquaria removals this population has been recovering.

- Comment from Ken Balcomb (cutting through the smoke and mirrors): if you choose any decade other than the mid-70s when the population was at its lowest, the SRKW population is in decline, not growing. There were 100-120 before the captures; there are 84 now. That’s a decline in my book.

- Comment: we ought to look at where these animals in every month of the year.

- Mamorek and Ford: we are not being consistent yet about defining each season.

9:01 John Ford of Northwest Fisheries Science Center comments (mp3)

- Reminded audience of workshop I and II data showing movements along outer coast at least from January through July.

- Diet information was under-emphasized. We had more than two samples and we have new data.

- Report makes overly simple assumptions about seasonal distribution