|

|

|

Sonar and Seismic Exploration: A Major Headache for Whales Use of Sound-based Technologies for Ocean Exploration Has Scientists Worried September 13, 2004 By Xanthe Pamboris AquaNews Correspondent

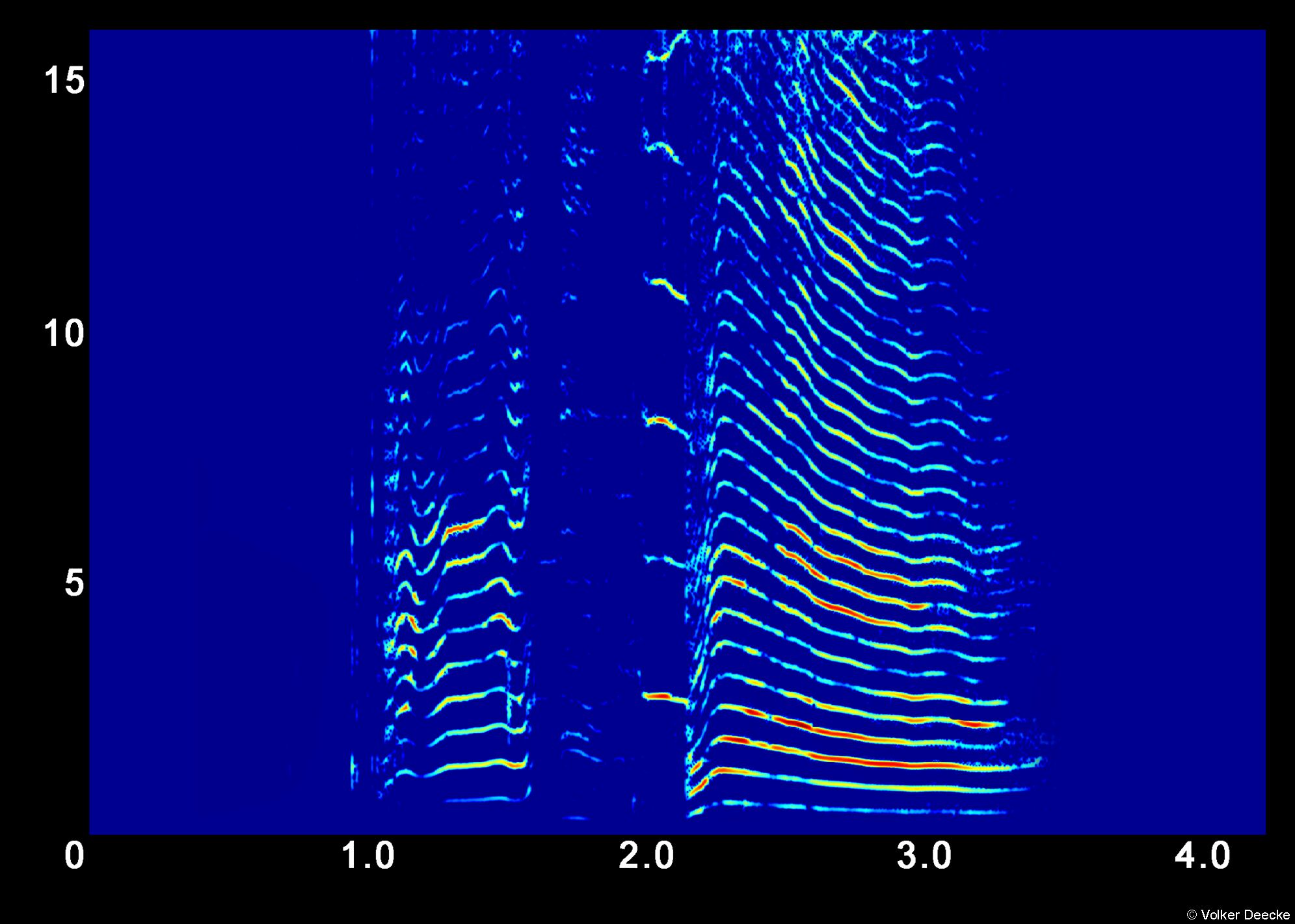

Imagine trying to function with a jackhammer thundering on and off outside your window, night and day. Dr Lance Barrett-Lennard, Senior Marine Mammal Research Scientist at the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Centre, uses this analogy to describe the deafening torment endured by whales in areas of oil and gas exploration. Noise is even more detrimental to marine mammals than to terrestrial creatures, as hearing is their primary sense. And because sound travels so well in water, the noise could be 50 kilometres away but will still seem like it is just around the corner. Marine noise is not a new phenomenon. Natural noises occur in the oceans constantly, including earthquakes, storms and singing baleen whales. However, it is the man-made noises that are causing problems: in particular, military sonar and the use of seismic testing for oil and gas exploration. The Navy uses sonar to detect enemy submarines. Sounds are emitted across the ocean and bounce back when they hit an object. The lower the frequency of the sounds, the further they travel. At present, mid-frequency active sonar (MFA) is in widespread use and low frequency active sonar (LFA) is being developed for use by the US and its allies. LFA sonar can generate one of the loudest sounds that it is possible for humans to make. Whales use their own form of sonar – echolocation – to navigate and to find food. They also use sound for communication. The loud and far-carrying noise of sonar is thought to disrupt the whales’ ability to navigate, forage and communicate. It is also believed to cause the whales to panic, inducing strandings and collisions. Mid-frequency sonar can cause whales to make a dramatic change in behaviour. On hearing sonar, whales may dive or rise deeply and rapidly. This can cause a form of decompression sickness, also known as ‘the bends’, resulting in sometimes fatal damage to the lungs, brain and ears. Sonar and Strandings The International Whaling Commission (IWC) recently released a report that backs up previous claims of the harm sonar can do. The report suggests that the noise produced by the military is damaging to cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) and in particular, rare beaked whales. The report cites recent cases, such as the unusual behaviour in Hawaii of 200 melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) in July 2004. These typically deep-water whales were observed swimming in a tight circle in shallow water just 100 feet from shore, showing clear signs of distress. One of the whales was later found to have died. This bizarre and near-stranding behaviour coincided with a U.S.-Japanese naval training exercise. A previous case documented the mass stranding of 17 cetaceans in the Bahamas in March 2000. Six of the dead animals, which included five Cuvier’s beaked whales and one Blainville’s beaked whale, were found to have experienced acoustic or impulse trauma that led to their stranding and subsequent death. The strandings also coincided with ongoing Naval activity using MFA sonar in the area. When other sonar exercises have taken place, mass strandings and whale mortalities have occurred. These include cases in the Haro Strait off the coast of Washington State, the Canary Islands, Madeira, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and in Greece. Despite numerous scientific studies and reports proving the damaging effects of sonar, the US Congress passed a new bill in November of last year that will allow the Secretary of Defense to permit the Navy to use sonar wherever and whenever they “need” to. A coalition of conservation groups, including NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) and The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), are threatening to sue the US Navy. They say the military’s use of mid-frequency sonar violates laws imposed to protect marine mammals, such as The Marine Mammal Protection Act, set up in 1972.

Seismic Exploration Another source of man-made marine noise is ‘seismic exploration’ or ‘seismic testing’, which is used by the oil and gas industry to detect the presence of fossil fuels underwater. It is similar to sonar in that both rely to varying extents on making sounds and listening for echoes. However, seismic exploration takes advantage of the fact that sound penetrates objects and surfaces to different degrees, depending on their geological or biological makeup. This enables engineers to locate oil deposits below the surface. While man-made sonar devices measure distances (the time interval between a sound pulse and its echo), seismic sounds continue for long periods and provide more of a chronic threat that can drive cetaceans from their critical habitat. Environmentalists are currently condemning plans by the Shell corporation to drill for oil in the Russian Far East. The proposed construction of an offshore drilling platform and the installation of a seabed pipeline near Sakhalin Island could threaten the survival of the area’s western gray whales, of which only 100 remain world-wide. In Canada, there are fears that a 32-year moratorium on oil and gas exploration off the BC coast may soon be lifted. As well as the considerable underwater noise that this would cause, there is also the risk of an oil spill. If the moratorium is lifted, exploration and drilling would take place in the Queen Charlotte Basin, which is home to endangered species such as the blue whale, sei whale, and North Pacific right whale, as well as killer whales, fin whales, beaked whales, dolphins and porpoises. According to Dr. Barrett-Lennard, if things are allowed to continue the way they are going, the outlook for marine mammals is not good. “Noise as a form of chronic environmental degradation is a relatively new notion,” he says, “but it is my opinion that seismic exploration and the use of sonar are two of the greatest threats to cetaceans at present, and all the indications are that they are going to get worse.”

Xanthe

Pamboris is a British freelance

|

Questions or comments about the AquaNews |

|

© Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science

Centre 2003 |