Today was the day of our final presentations. After a solid week of limited sleep (one night I went to bed at 3:30 AM, and I was the first one) and lots of work, it’s a relief to finally have all that stress lifted off our shoulders. It’s given me a chance to really think about our time here. It’s had its ups and downs. When you’re living in a confined space for an extended period of time with the same people, morale can quickly spiral downwards. The final deadline looming over our heads definitely made for some stress. However, most of our boat life was extremely enjoyable. It won’t be the stressful times that we’ll remember when looking back on this trip, it will be all the times that we really enjoyed. There are a lot of things that I will really miss:

1)     Rough seas. The was nothing quite like sitting on the trampoline, rising up on the crest of a large wave only to watch with mild horror as the water simply disappeared underneath you for a minute before rushing up to soak you before you had a chance to even comprehend what’s going on. Rough seas were also fun in the cabin. Whenever Captain Todd yelled in, “You might want to hold on and secure loose items,†a frantic response was initiated as everyone rushed to grab onto their possessions. Then the boat pitched and wreaked more havoc on the galley than a small earthquake. Sure, it could be nauseating. But as long as your computer didn’t crash to the ground (which did happen on more than one occasion), you couldn’t help but laugh.

2)     Sitting out on the trampoline. It was definitely my favorite place on the boat. It was also a great place to nap. It was so relaxing sitting out there, scanning the water for whatever might be out there.

3)     How sweet chocolate tasted on the boat. I swear, chocolate never tasted so good. Especially those NOLS malt balls.

4)     Finding shrimp swimming around in the toilet. I kid you not, it happened. Then you’d have to scoop him out because you didn’t want to condemn him to a miserable death in the sewage tank.

5)Â Â Â Â Â Stirring up the water out the escape hatch at night and watching the Noctiluca produce bioluminescence.

6)Â Â Â Â Â How gorgeous the stars were every night.

7)     Calling every whale watch operator we could think of in the morning in a desperate attempt to find the whales. These calls would sometimes turn into very pleasant chats, and we all made friends with the operators.

8)     Being able to plot our own course every day. If we wanted to go around Whidbey Island, we could. And did.

9)Â Â Â Â Â How good a hot shower felt after a week of feeling cold and dirty all the time.

10)Â Sea hair.

11)Â Discovering new plankton names that sound like dinosaurs.

12) How cold it was every night… oh wait, no I won’t miss that.

13)Â The Aladdin lamp.

14) How beautiful everything out here is. We had the opportunity to visit so many awesome places, from Deception Pass to Active Pass way up in Canada. Each adventure was more exciting and beautiful than the last.

15) Home-cooked popcorn. Who knew it was so much better than microwave popcorn?

16) The whales, of course. Let me tell you, there is nothing more exciting than seeing that first blow and then getting to spend hours with these amazing animals. To make it even better, we got to listen to them underwater as we were observing them above water as well. Every day that we spent with the whales became my “best day ever.â€

17) All the amazing people that I met. I’d like to give a special thanks to all of the guest speakers that took time out of their busy schedules to meet with us. It’s been amazing. Also, to Ally, Emalie and Kelsey for helping to make this experience fun. I’ll miss them all terribly, and hope that I’ll get to see everyone again sometime in the future.

This program has been a really great opportunity. It has given us an intimate taste of what field research is like, and has definitely helped me to shape my future path. We’ve all learned so much, and I’m excited to be able to share this newly acquired knowledge with others. For a really great video on Beam Reach made by our fantastic videographer, Carlos, check this out. It’s a good summary of our experience.

I’ve wanted to study whales ever since I was three years old and first watched the movie ‘Free Willy’. I was extremely lucky to get the opportunity to actually do this. If you ever get such an opportunity to follow your dream, go for it. You never know what you might find.

Transient orca

Read More

Yesterday we got back from our two week session at sea. We had a rough start. Our first ten days were whale-less. Sure, J pod was around, but we always seemed to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. At one point we got a call that the whales were up in Active Pass. We couldn’t catch up to them, but we anchored strategically at Patos Island. That way, when they came through Active Pass we could see them if they went down either Boundary Pass or President’s Channel. To be sure that we didn’t miss them, we posted anchor watch that night. We each took two hour shifts listening to the hydrophone all night. I slept outside in hopes that I would hear their blows if they came by. None of us heard anything, so the next day we set ourselves up so that we had a view of everything. I got hoisted up onto the mast to have a better view of the surrounding water. We were there half the day before we heard that there were whales down south at Lime Kiln. Of course. They must have gone up Active Pass and then turned around and gone back the way they came, which they almost never do. We were six hours away, and by the time we made it down to Snug Harbor the whales had gone back out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Our week continued like that until the Saturday before we got off the boat. We were headed out of Snug when Robin told me that she had seen a minke from the road on her way over. She figured that it’d be long gone, but I decided to go out and check anyway, just in case the whale had slowed down. I was out looking for no more than two minutes before Ally came out and asked what I was looking for. As I turned and told her, she suddenly pointed and said, “What’s that?” It was our whale!  As the whale arched its back, it was obvious that it was not a minke, but actually a humpback! Surprise #1! Another blow rose up and glistened in the sun. Surprise #2! There were actually two whales! It was exceptional. Humpbacks are rarely seen in Haro Strait, so it was a real treat. The local humpback population was destroyed by commercial whaling operations in the early 1900s. In fact, the whole Salish Sea population was wiped out in just one season of industrial whaling. They are only just starting to return a century later. We were lucky enough to get to observe two of these leviathons. I have had the opportunity to see a lot of humpbacks on whale watches on the East Coast, and they are always my favorite to see. They’re known for being extremely active and acrobatic. These whales did not disappoint. We were treated to just about every surface behavior imaginable. One whale breached, then performed a series of chin slaps before finishing with another breach. One of the whales slapped his pectorals repeatedly, giving us a beautiful display of his “big wings” that give humpbacks their Latin name (Megaptera novaeangliae translates to ‘big-winged New Englander’). It was fantastic. We also got some good looks at the flukes of the humpbacks. The markings on the undersides of the flukes are like a human’s fingerprint. The unique patterns and pigmentation are used to identify individual whales. For a catalog of the humpbacks that are seen in these waters, check out this site.

Just two days after this, we were performing a spreading and localization exercise when we got a text saying, “Many whales between False Bay and Lime Kiln.” When we spotted the first blows and fins I was incoherent with excitement (literally – Captain Todd had to ask me to calm down enough so that he could understand what I was saying). Finally, after three weeks of searching, J pod had come to us. It was amazing. The whales were extremely vocal, and we were the last boat with them, so we got some great recordings with minimal boat noise. We also witnessed a lot of surface active behaviors, including cartwheels, which was fantastic. We managed to remain with J pod for four hours. Even if it took us three weeks to find them, it was well worth the wait! I can’t wait to go back out and hopefully find them again!

Read More

Yesterday we returned from our first week at sea on the Gato Verde! It was an absolutely fantastic week, even though the orcas managed to elude us. We went where no Beam Reach group has gone before: all the way around Whidbey Island via Saratoga Passage and through the narrow, turbulent Deception Pass! In case you didn’t know, Whidbey Island is BIG! In fact, it’s the largest island in the state of Washington, and the fourth largest in the lower 48 states. It took us several full days of cruising and a 5:30 AM hail-and-rain-filled departure from anchorage to make it all the way around.

However, we got an incredible taste of the marine life of the Salish Sea. We were treated to sights of river otters, harbor seals, California sea lions, Stellar sea lions, harbor porpoises, gray whales, and even an elusive minke whale! After shooting through Deception Pass, we surprised a California sea lion, who popped up right in front of our boat and proceeded to glare us down for the intrusion. We got to watch a gray whale slowly feeding up and down the coastline. Our first cetacean encounter of the trip was of a minke whale breaching at least five times in quick succession in Admiralty Inlet. I have seen a lot of minkes on various whale watching trips on the East Coast. Usually they just pop up a few times and then disappear. I have NEVER seen one breach. This was most certainly the highlight of the trip for me so far.

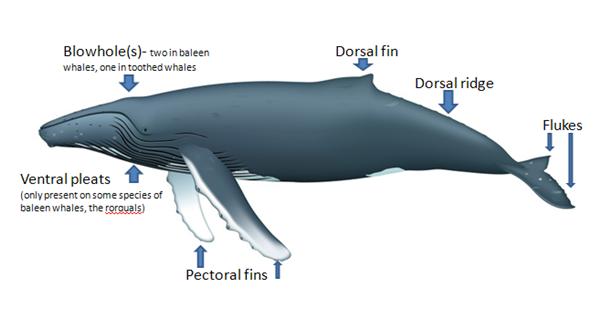

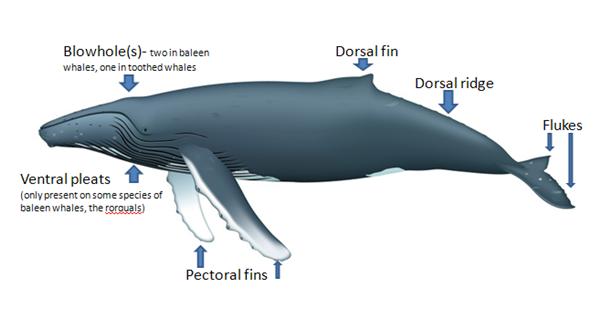

However, we were confronted with a problem when reporting the minke whale. No one believed us. It turns out a humpback whale was also sighted breaching that day in about the same area. As breaching is much more commonly observed in humpbacks than in minke whales, everyone assumed that we had mixed the two up and had actually seen the humpback. If Val hadn’t been quick and snapped a picture of the dorsal fin, most likely no one would have believed us. It turns out that this is a common problem. Seeing as how we usually only get to see such small parts of the whales above the water, it is very easy to get the different species confused. I decided to compile a quick guide of some of the more commonly sighted species of cetaceans in the Salish Sea in an effort to make it easier to properly identify these species when spotted! Below is a diagram of a humpback whale. Some key features that I will be discussing are labeled. All photos are taken by me unless otherwise labeled.

CETACEAN 101

A) The Mysticeti, or baleen whales.

A) The Mysticeti, or baleen whales.

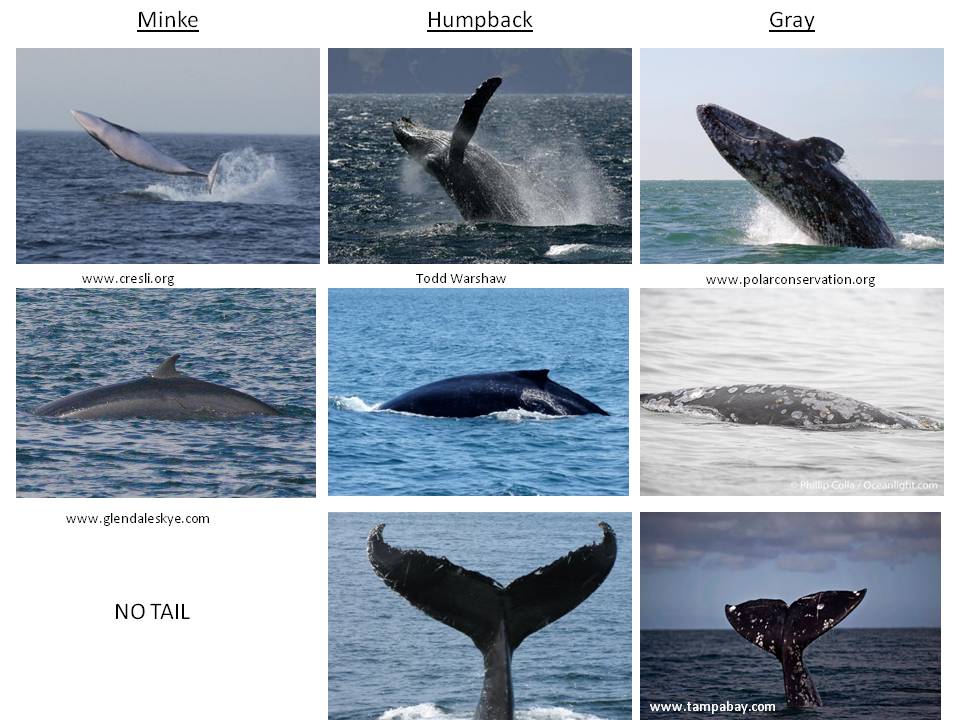

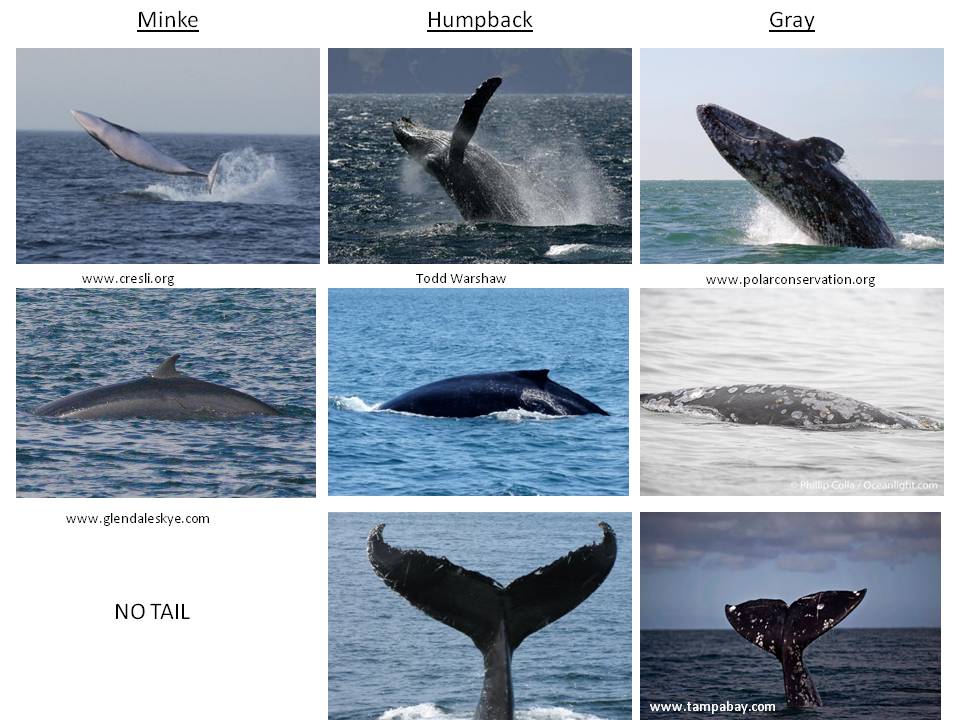

1. Minke Whale– The minke is the smallest of the baleen whales. They are roughly the size of an orca, and are dwarfed by the larger gray whales and humpback whales. Being so small, their blows are not always easily seen. Their bodies are small and torpedo-like, with small pectoral fins with a white band going across them. If you are lucky enough to see them breach, as we did, you can easily see this.

Note the smooth, torpedo-like shape. The white band on the pectoral fins is clearly visible, and the small pectorals are tucked in close to the body. The minke whale is part of the rorquals, so they do have ventral pleats. However, you have to be quite close to be able to distinguish these pleats.

Breaching is a rare thing to see in a minke; they are typically shy and elusive, so more frequently you only see their back and dorsal fin. No fear though, as the minke dorsal fin is also fairly easy to distinguish from other cetaceans in the Salish Sea. As with all baleen whales, the dorsal sits about 2/3 of the way back on the body, so it is preceded by a fair amount of back before the dorsal fin can be seen. The dorsal is small and distinctively curved.

Another thing to look for in minkes is lunging behavior. These whales often lunge feed; they create a bait ball and then lunge through the middle and can sometimes come partly out of the water. Minke whales are perhaps easiest to confuse with fin whales. While these guys are rare visitors to the Salish Sea, it is still worth noting the difference, as they are sometimes seen here. Fins also have small, hooked dorsals that look quite similar to minkes. However, the fin whale tops out at around 80 feet, and is the second largest creature on earth. This is much bigger than the 30 foot minke. While it can be tricky to distinguish from a distance, size is the key feature to look for in this case.

Minke whales are known to make “boing” sounds. Most of the energy in these calls is between 1 and 2 kHz, which is well within the hearing range of humans. An example of their call can be heard here.

2. Humpback Whale– Humpbacks are larger (between 40-50 feet) members of the baleen whale family. When you know what you are looking for, humpbacks are pretty easy to distinguish from other species of cetaceans. Their blow is usually more visible than the blow of a minke. See the picture below to note what to look for in the blow.

Humpbacks are also known for being one of most acrobatic of the whales. They frequently breach, spy hop, slap their pectorals, and slap their flukes. If you see a whale doing any of these behaviors, look closely. The most obvious feature of the humpback whale is its pectoral fins. Their scientific name, Megaptera novaeangliae, literally means “large-winged New Englander.” Long and often white, the pectorals are very obvious and are a dead giveaway that you are looking at a humpback.

Humpback whales are also known to fluke, which is when they deep dive and show their tails. All the whales have distinct white patterns on the underside of their flukes. These patterns are used to identify individual whales. Minke whales do not usually show their flukes. Gray whales do on occasion, but humpback whale tails are distinct in shape.

If you only see the dorsal fin of the whale in question, it is also fairly easy to tell which kind of whale it is, especially if you get a picture! Humpback dorsal fins have a small bump in the front and then a sickle-shaped curve. They are also well-known for “humping” their backs right before they dive.

Humpbacks are known for being very vocal, and males compose long, haunting songs that carry for miles. An example of a humpback song can be found here. However, these songs are sung primarily at the breeding grounds of humpbacks, presumably to attract mates, although this isn’t known for sure. Humpbacks found in the Salish Sea are more likely to be making a feeding call.

3. Gray Whale– Gray whales are rather prehistoric looking whales that can be found in the spring, summer and fall in the Salish Sea. These whales like to feed along the bottom in shallow waters, and so are frequently seen foraging close to shore. They are covered in barnacles and whale lice. These patches of parasites can help distinguish individuals.  The blows of gray whales are bushy and heart-shaped.

Gray whales also don’t have a dorsal fin, instead they have a prominent dorsal ridge.

Gray whales tend to roll on their side and scrape along the muddy bottom in search of food. Because they feed in shallow water, this often exposes their pectoral fin. They also sometimes show their flukes, which are smaller and more square-shaped than those of humpbacks.

If you wish to try to identify a gray whale that you spotted, check out the gray whale ID guide from Cascadia Research Collective.

The vocalizations of gray whales are typically series of grunts. The average frequency is typically around or below 1 kHz.

A quick comparison of these three most common species of baleen whales found in the Salish Sea:

B. The Odontoceti, or toothed whales

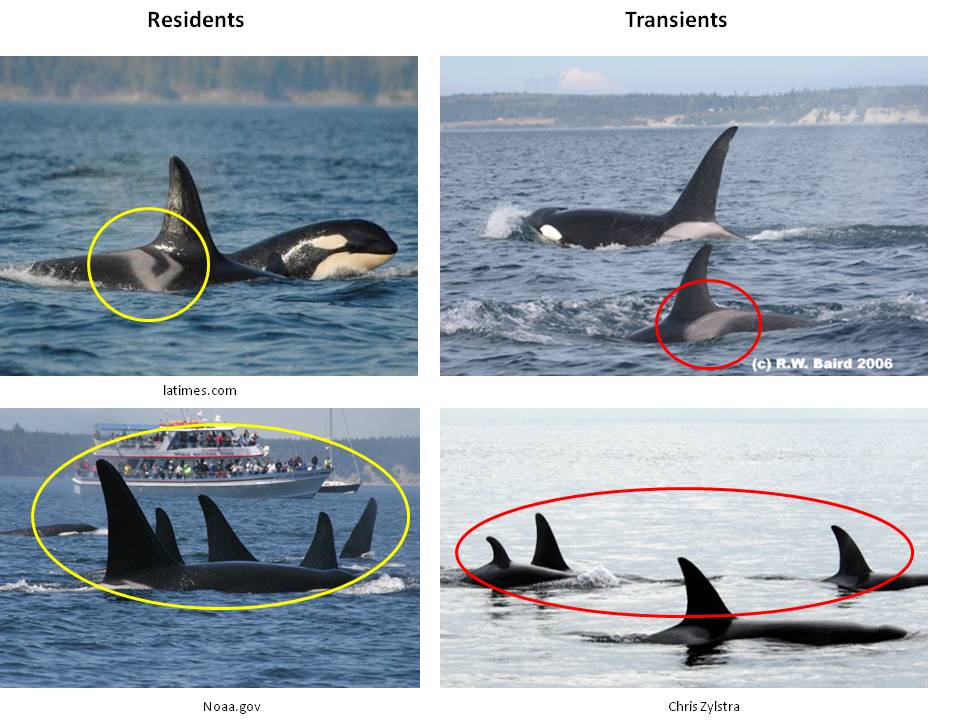

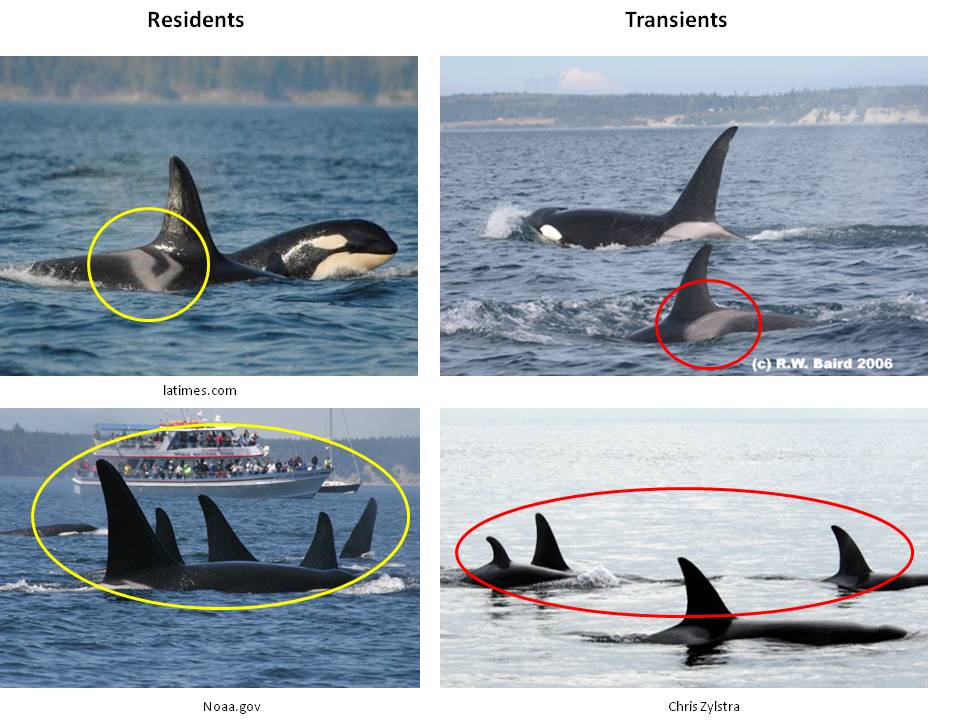

1. Killer Whale, or orca- The orca is the most easily distinguished cetacean in the Salish Sea. Actually the largest member of the Dolphin family, the orca can be recognized by it’s black and white color pattern. Males sport dorsal fins up to six feet tall, while females have smaller, curved dorsal fins. The gray saddle patch behind the dorsal fin can be used to identify individual killer whales.

Of the three ecotypes of killer whales (residents, transients, and offshores), only residents and transients are found with any regularity in the waters of the Salish Sea. While it can be difficult to distinguish these two, it is not impossible. The southern residents (SRKWs) are found in relatively large, stable family pods, while transients are typically (but not always) found in smaller pods. Of course, the SRKWs eat only fish, while the transients prey on marine mammals. So if you see a killer whale pursuing a sea lion or other mammal, it is a transient. Transients and residents can also be distinguished by their dorsal fins and saddle patches. The SRKWs have more rounded dorsal fins than transients, and they can have open saddle patches, while the transients have solid gray saddle patches. Residents and transients can also be distinguished by their calls. Residents are much more vocal, and tend to have an almost up-beat, bubbly sound to their calls. Transients typically make fewer vocalizations that have a rather haunting quality to them.

2. Pacific White-sided Dolphin- While Pacific white-sided dolphins aren’t seen frequently in the Salish Sea, they are seen at times during the summer and fall. These dolphins are relatively small, around eight feet long. They have a dark upper body, with a light underside and gray stripes running along their sides. They also tend to show more of their bodies when surfacing than the porpoise species found in the Salish Sea. They make high frequency, whistle-like vocalizations.

3. Harbor Porpoise- Harbor porpoises are small members of the Phocoenidae family. They are gray-brown on top with a light underside. They have a triangular fin. Harbor porpoises are often seen in fairly shallow water, and can be found around the mouths of rivers. They are typically found in small groups of less than ten individuals. Harbor porpoises typically make acoustic signals that are above the hearing range of humans, but it is possible to slow the calls down to allow humans to hear them.

4. Dall’s Porpoise- Dall’s porpoises have a black and white coloration that is similar to that of orcas, leading to them occasionally being incorrectly referred to as baby orcas. Measuring around 6 feet, the lack of an eye patch and shape of the dorsal fin immediately give the animal away as being a Dall’s porpoise rather than an orca. Dall’s porpoise are very fast cetaceans, and often create a “rooster tail” of spray when bow-riding. They have a small white patch on their triangular dorsal fin, helping to distinguish them from harbor porpoises. They are stockier than harbor porpoises, with a narrow, distinct peduncle (area immediately in front of tail). Like harbor porpoises, Dall’s porpoise produce acoustic signals that are too high for most humans to hear. However, when brought down to a frequency within our hearing range, they make a series of click-like sounds. Scripps Whale Acoustic Lab has a nice recording of a Dall’s porpoise here (For whatever reason I can’t link directly to it, so click on Porpoises, Dall’s porpoise, and then play call).

Comparison of toothed whales found in the Salish Sea:

Well that about wraps it up for the cetaceans of the Salish Sea! I hope that this helps provide a guide for identification of the cetaceans in this area.

Well that about wraps it up for the cetaceans of the Salish Sea! I hope that this helps provide a guide for identification of the cetaceans in this area.

On a quick side note, I would like to thank everyone who was on the Gato Verde with us this past week, and give a special thanks to Val and Leslie for cooking us a fantastic Easter brunch and letting the Easter Bunny into S1 to hide chocolate eggs for all of us! 🙂

Also, while writing this blog post, I was interrupted by orca calls on the Lime Kiln hydrophones. Carlos was super nice and drove us all down to Lime Kiln, where we got our first sighting of J Pod!!! It was extremely exciting, probably one of the best days of my life. One whale even breached right off shore from us twice! I’d like to leave you all with this photo of a whale porpoising by us at LK. Jeanne was also watching from shore; she got some IDs and posted a recording of the calls on her blog!

Read More

“What are the effects of cars on whales?” This week, we were all asked this question by the extremely knowledgeable killer whale researcher Dave Bain. We all sat there, staring blankly and not coming up with any potential impacts. We could think of nothing. However, it turns out cars are one of the top threats to the marine mammals. Everything from oil spills, to abundance of prey, to threats to the whales from alternative energy are influenced by them.

It’s a theme that we’ve been learning a lot about in the past couple weeks. Our terrestrial environment has remarkable

Enjoying the mud at Beaverton Marsh!

effects on the marine ecosystems. It’s something that isn’t thought of that much, with the exception of direct dumping into the environment and potential contamination of groundwater. But it is a concept that deserves more attention. This terrestrial impact has been the focus of our service projects this year, and rightfully so. Last week, we helped work on the enhancement and restoration of Beaverton Marsh. Over the years, the invasive reed canary grass has taken over the wetland, which has fallen victim to agricultural overuse. The restoration project aims to help restore native species and increase the diversity of the marsh. So for a couple of hours we all sloshed around in the mud and put plant protectors and mulch on plants that had been previously planted. It was hard work, but well worth the effort. Plus, it was a GORGEOUS day, which made it very enjoyable!

Last Friday we spent the day helping out on an organic local farm. We toured the farm and learned

Sweet Earth Farms- photo by Carlos Sanchez

a bit about organic farming on the island. We talked about permaculture, which is a type of agriculture that tries to model natural processes in nature. For example, there is a heavy focus on the use of perennial plants over annual plants (which need to be planted every year). The majority of plants found in the wild are perennials, which have a very stable root system. These long, deep roots absorb nutrients more efficiently, and so generally require less maintenance than annuals, and don’t deplete the topsoil as much. For more information on the use of perennials vs. annuals, check out this article from National Geographic.

Now you might be wondering what all of this really has to do with whales. It turns out, a lot! The three main threats to the southern resident killer whales were listed as being: 1) Prey availability, 2) Vessel noise, and 3) Toxins. The terrestrial environment can have a large effect on both prey availability and toxins. Degradation of the spawning environments of Chinook salmon can limit the returns of the fish back to the ocean. These rivers are easily affected by humans and agriculture. Cattle and other livestock can erode the river and stream banks and the removal of riparian vegetation leads to decreased shelter from predators (provided by shade) and increased temperatures that could rise to undesirable levels for the cold-loving salmon. Agricultural runoff creates an influx of nutrients that can lead to eutrophication and decreased oxygen content in water bodies. Dams create barriers to salmon migration to spawning areas. All of these lead to less fish for the killer whales to eat.

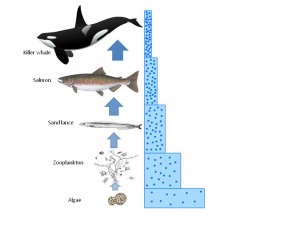

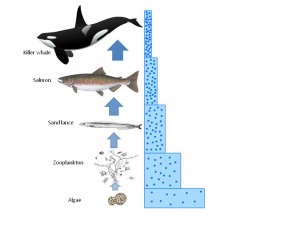

Toxins also pose a huge threat to the killer whales. High on the trophic pyramid, the killer whales suffer from the bioaccumulation of chemicals (see diagram at right). High levels of DDT, PCBs, and PBDEs have been found in killer whales. These are all organic chemicals that don’t breakdown well, leading to relatively high levels in the mari ne environment, even for the now illegal DDT. Indeed, many pesticides are a problem. Kwiaht in 2008 found that pyrethroid pesticide levels in the San Juan County waters averaged 1-2 parts per billion, with much higher levels in some areas. Levels of 1 part per billion are known to be toxic to salmonids. Surfactants, which are chemicals used to mix water and oil, are present in nearly every man-made product. The Friday Harbor Aquarium found lethal levels of surfactants in the surrounding water.

ne environment, even for the now illegal DDT. Indeed, many pesticides are a problem. Kwiaht in 2008 found that pyrethroid pesticide levels in the San Juan County waters averaged 1-2 parts per billion, with much higher levels in some areas. Levels of 1 part per billion are known to be toxic to salmonids. Surfactants, which are chemicals used to mix water and oil, are present in nearly every man-made product. The Friday Harbor Aquarium found lethal levels of surfactants in the surrounding water.

All of these toxins come from the terrestrial environment. It is important to be conscious of what we’re pouring down the drain or dumping outside. The San Juan Islands were heavily glaciated in the last ice age, which has resulted in very thin soils in many areas. Soil typically helps to filter groundwater. This decreased filtration can lead to increased runoff of chemicals to the marine environment. It’s important to be conscious of what we’re pouring down the drain or dumping outside. Try to minimize the amount of chemicals poured down the drain. Take care of your septic system to help prevent leakage. Restoration projects help bring back native species which help balance the ecosystem. Sustainable agricultural processes help reduce the runoff of toxic pesticides and other chemicals. So be cautious, be aware, and help protect these iconic animals!

Read More

Olympic Mountains from Lime Kiln

Hello all! My name is Mandy, and I am a 3rd year Wildlife Ecology major from the University of Maine. We are already a week into the Spring ’11 Beam Reach program, and it would be an understatement to say that it’s been an eventful week so far.

We started our week off with a trip to Lime Kiln State Park (also known, appropriately so, as Whale Watch State Park). The State Park was absolutely GORGEOUS. It was a beautiful, sunny day, and you could see the Olympic Mountains towering over the water (above). Just as some background information about the park, it was mined for limestone to make into concrete back in the late 18 to 1900s. Kilns were built at the park to produce lime. This resulted in a lot of deforestation on the island, as trees needed to be cut down to keep the fires in the kiln going. Now, however, the forests are coming back, especially in the park area. We got to walk back and see one of the kilns that’s still standing, which was very cool.

So at any rate, we went to the park to brainstorm and discuss questions. We got to sit out on the rocks, in this beautiful setting, and come up with questions, then moved inside to the warmer lighthouse to discuss our questions with everyone. It was as we were discussing our questions that it happened. Kelsey was talking to Scott about one of her questions, when all of a sudden she stopped talking, left her mouth hanging open, and just kind of stared off out the window over Scott’s shoulder. Then her eyes got huge. It was most definitely the face of someone who had seen something. Turns out, she hadn’t just seen something, she had seen ORCAS! We all promptly grabbed binoculars and ran outside. There was a group of what turned out to be about 9 whales. We watched them a bit from the Light House, then ran and hopped into the car and journeyed up to Val’s house. We got there just in time, as they were passing right by. They were a ways out, but they were lunging and were definitely visible.

It was awesome because, not only were they killer whales, but they were transients! Apparently there was about a 1 in a 1,000 chance that we would ever see them. The hydrophone never picked up any calls, so we were very lucky that Kelsey happened to be looking in the right place at the right time. We were also mentioned (although not by name) in a blog by Jeanne (check it out), who we all hope to meet soon!

So, for those of you who don’t know, there are three different ecotypes of killer whales found in these waters. The first is residents (such as the beloved Southern Resident killer whales (SRKW) that we will be focusing our research efforts on, as well as the Northern Residents). The resident pods are fish-eating pods. They eat primarily Chinook salmon. Our SRKWs are found in three pods: J, K, and L. They are known for being quite vocal (which makes them prime candidates for bioacoustic research). In contrast, transients are mammal-eating. They are usually found in smaller pods, and are usually much quieter then residents are.  Then there are the offshore killer whales. Although believed to be genetically closest to residents, very little is known about offshores. They are usually found in large groups out in more open water, and it is believed that they feed on sharks and other fish. Offshores are also typically smaller than the other two ecotypes, and they make strange and haunting calls (Offshore calls were recently picked up on hydrophones in our area, and were recorded by Jan Twillert from Holland, an active listener of the hydrophone network maintained by Paul and Helena Spong at the north end of Vancouver Island).

Seeing the transients has definitely been the highlight of the program for me so far. However, it has all been awesome. I can’t get over how fantastically gorgeous it is out here. The islands are beautiful, and everyone is so friendly. We’ve learned a ton too. Probably my favorite talk was by Monika Wieland, who told us a little about the natural history of the SRKWs. She told us a lot of interesting stuff about the whales, and also a lot about acoustics. Jason Wood talked about bioacoustics, which was very interesting for me, as I’ve done a bit of acoustical work with bats in New York. Kari Koski came in and talked to us about the Soundwatch Program, which helps educate boaters on ‘being whale-wise.’ Because there has been evidence that the whales are affected by the constant vessel traffic around them, this is extremely important. Finally Anna Kagley talked to us about salmon in the area, which I thought was really interesting as well. Obviously, as the SRKWs primary prey, the fate of the salmon is tied with the fate of the whales. Furthermore, I read about a study done by Drs. Eric Ward and Eli Holmes, whose preliminary results suggest that the birth rate of the whales is most affected by Chinook salmon abundance than any of the other threats analyzed (vessel interactions and exposure to toxins). Therefore, it’s very good that efforts are being made to help understand the Chinook salmon population!

Vessels and resident whales... Helps highlight one of the threats to the whales (Photo credit to Kari Koski)

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook