Traditional vs. Supplemental Hatcheries

Fish hatcheries have become ever more important in recent years due to the declines in wild stocks. The aim of hatcheries is to replenish the wild stock in order to keep the fishing industry sustainable, but there is still debate as to what is the best approach to this without causing further damage to the wild population. In an attempt to make improvements to hatchery practices, Hitoshi Araki studied the reproductive success of hatchery trout compared to wild trout, and made suggestions in his paper Hatchery Stocking for Restoring Wild Populations: A Genetic Evaluation of the reproductive Success of Hatchery Fish vs. Wild Fish (2008).

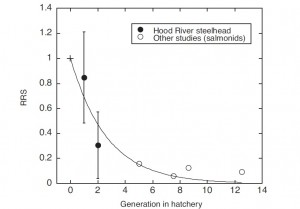

The hypothesis was that fish bred using the traditional hatchery methods, in which the fish are usually non-local and are bred for many generations in captivity, have much lower reproductive success than both supplemental hatchery fish and wild fish. The idea behind supplemental hatchery methods is to use local parent fish to breed “wild stock” hatchery fish in a protected environment, and then release them into the wild population, with the overall goal being to re-create a sustainable wild population. Using DNA analysis of steelhead trout from the Hood River, Araki determined the reproductive success of traditional hatchery fish, supplemental hatchery fish, and wild fish. He found that the more generations bred in a hatchery, the less reproductively successful the fish are.

Picture 1: Araki used his own data and data from previous studies to show the decline in relative reproductive success (RRS) as the number of generations in a hatchery increased.

Araki also found that supplemental hatchery fish had significantly higher reproductive success than the traditional hatchery fish, though they still had lower reproductive success than the wild population. When a wild stock parent was crossed with a traditional hatchery parent the reproductive success dropped. This shows the effect that hatchery fish can have on the wild population. If traditional hatchery fish continue to be released into wild populations in attempt to sustain them, they will continue to lower the reproductive success of the wild population.

It seems that, though hatcheries have a positive sustainability goal in mind, the traditional methods they are using to replenish wild stocks are somewhat counter-acting what they are trying to achieve. Though it may be more work to implement supplemental hatchery methods, the benefit of higher reproductive success of the population should be worth it.

Araki used steelhead trout as his example organism, but it is assumed that similar principles could apply to other fish species. In the San Juan and Vancouver Island area, salmon hatcheries are an important part of the fishing industry (and produce important food for the Southern resident orcas!). Since Chinook salmon are endangered in the area, a large amount of juveniles are released into the wild from hatcheries. From the information I could find, it seemed hatcheries in the area are attempting to use methods closer to supplemental techniques rather than the traditional methods. For example, the San Juan Enhancement Society in Port Renfrew, BC collect their broodstock (parent fish) of Chinook from a lake connecting to the San Juan River, therefore the juvenile fish are being released into their natural habitat. Though it isn’t stated how many generations are produced in the hatchery, it still could be considered a step in the right direction compared to using a non-local broodstock. Hopefully in the future hatcheries move towards supplemental practices so that the wild stocks, the ecosystem, and everyone utilising the fish can further benefit from sustainable fish populations.

Picture 2: Both wild and hatchery juvenile Chinook can be found in the San Juan Islands, as our Beam Reach class found out while beach seining on Lopez Island. The hatchery salmon had their fins clipped for identification.

Picture 2: Both wild and hatchery juvenile Chinook can be found in the San Juan Islands, as our Beam Reach class found out while beach seining on Lopez Island. The hatchery salmon had their fins clipped for identification.

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook