Salish Sea Cetaceans 101

Yesterday we returned from our first week at sea on the Gato Verde! It was an absolutely fantastic week, even though the orcas managed to elude us. We went where no Beam Reach group has gone before: all the way around Whidbey Island via Saratoga Passage and through the narrow, turbulent Deception Pass! In case you didn’t know, Whidbey Island is BIG! In fact, it’s the largest island in the state of Washington, and the fourth largest in the lower 48 states. It took us several full days of cruising and a 5:30 AM hail-and-rain-filled departure from anchorage to make it all the way around.

However, we got an incredible taste of the marine life of the Salish Sea. We were treated to sights of river otters, harbor seals, California sea lions, Stellar sea lions, harbor porpoises, gray whales, and even an elusive minke whale! After shooting through Deception Pass, we surprised a California sea lion, who popped up right in front of our boat and proceeded to glare us down for the intrusion. We got to watch a gray whale slowly feeding up and down the coastline. Our first cetacean encounter of the trip was of a minke whale breaching at least five times in quick succession in Admiralty Inlet. I have seen a lot of minkes on various whale watching trips on the East Coast. Usually they just pop up a few times and then disappear. I have NEVER seen one breach. This was most certainly the highlight of the trip for me so far.

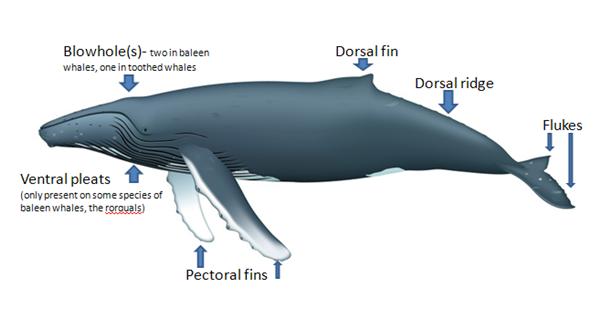

However, we were confronted with a problem when reporting the minke whale. No one believed us. It turns out a humpback whale was also sighted breaching that day in about the same area. As breaching is much more commonly observed in humpbacks than in minke whales, everyone assumed that we had mixed the two up and had actually seen the humpback. If Val hadn’t been quick and snapped a picture of the dorsal fin, most likely no one would have believed us. It turns out that this is a common problem. Seeing as how we usually only get to see such small parts of the whales above the water, it is very easy to get the different species confused. I decided to compile a quick guide of some of the more commonly sighted species of cetaceans in the Salish Sea in an effort to make it easier to properly identify these species when spotted! Below is a diagram of a humpback whale. Some key features that I will be discussing are labeled. All photos are taken by me unless otherwise labeled.

CETACEAN 101

A) The Mysticeti, or baleen whales.

A) The Mysticeti, or baleen whales.

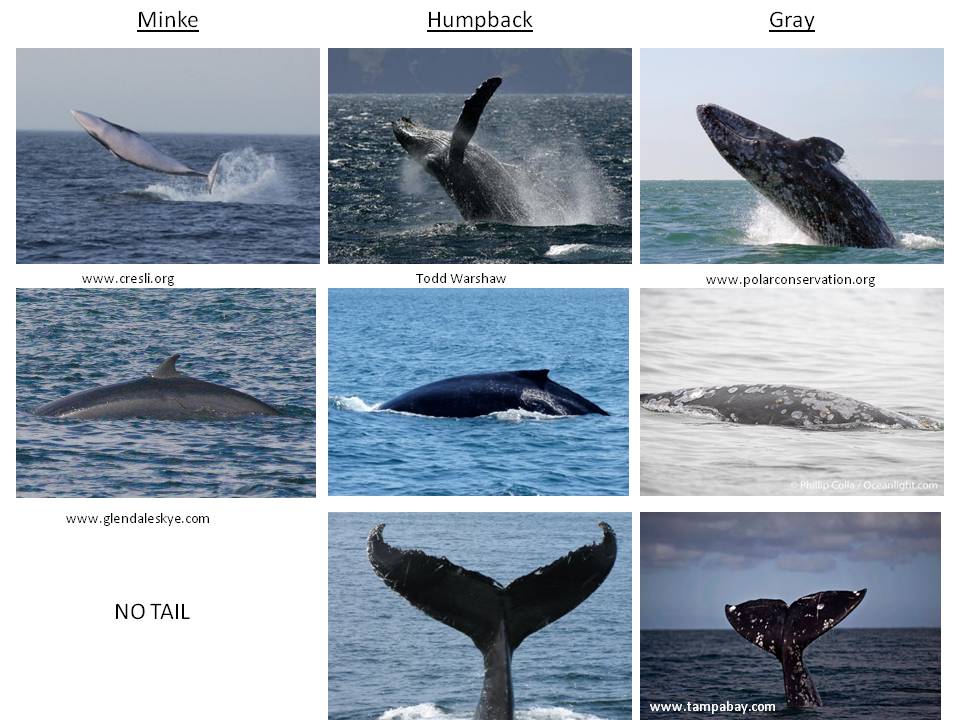

1. Minke Whale– The minke is the smallest of the baleen whales. They are roughly the size of an orca, and are dwarfed by the larger gray whales and humpback whales. Being so small, their blows are not always easily seen. Their bodies are small and torpedo-like, with small pectoral fins with a white band going across them. If you are lucky enough to see them breach, as we did, you can easily see this.

Note the smooth, torpedo-like shape. The white band on the pectoral fins is clearly visible, and the small pectorals are tucked in close to the body. The minke whale is part of the rorquals, so they do have ventral pleats. However, you have to be quite close to be able to distinguish these pleats.

Breaching is a rare thing to see in a minke; they are typically shy and elusive, so more frequently you only see their back and dorsal fin. No fear though, as the minke dorsal fin is also fairly easy to distinguish from other cetaceans in the Salish Sea. As with all baleen whales, the dorsal sits about 2/3 of the way back on the body, so it is preceded by a fair amount of back before the dorsal fin can be seen. The dorsal is small and distinctively curved.

Another thing to look for in minkes is lunging behavior. These whales often lunge feed; they create a bait ball and then lunge through the middle and can sometimes come partly out of the water. Minke whales are perhaps easiest to confuse with fin whales. While these guys are rare visitors to the Salish Sea, it is still worth noting the difference, as they are sometimes seen here. Fins also have small, hooked dorsals that look quite similar to minkes. However, the fin whale tops out at around 80 feet, and is the second largest creature on earth. This is much bigger than the 30 foot minke. While it can be tricky to distinguish from a distance, size is the key feature to look for in this case.

Minke whales are known to make “boing” sounds. Most of the energy in these calls is between 1 and 2 kHz, which is well within the hearing range of humans. An example of their call can be heard here.

2. Humpback Whale– Humpbacks are larger (between 40-50 feet) members of the baleen whale family. When you know what you are looking for, humpbacks are pretty easy to distinguish from other species of cetaceans. Their blow is usually more visible than the blow of a minke. See the picture below to note what to look for in the blow.

Humpbacks are also known for being one of most acrobatic of the whales. They frequently breach, spy hop, slap their pectorals, and slap their flukes. If you see a whale doing any of these behaviors, look closely. The most obvious feature of the humpback whale is its pectoral fins. Their scientific name, Megaptera novaeangliae, literally means “large-winged New Englander.” Long and often white, the pectorals are very obvious and are a dead giveaway that you are looking at a humpback.

Humpback whales are also known to fluke, which is when they deep dive and show their tails. All the whales have distinct white patterns on the underside of their flukes. These patterns are used to identify individual whales. Minke whales do not usually show their flukes. Gray whales do on occasion, but humpback whale tails are distinct in shape.

If you only see the dorsal fin of the whale in question, it is also fairly easy to tell which kind of whale it is, especially if you get a picture! Humpback dorsal fins have a small bump in the front and then a sickle-shaped curve. They are also well-known for “humping” their backs right before they dive.

Humpbacks are known for being very vocal, and males compose long, haunting songs that carry for miles. An example of a humpback song can be found here. However, these songs are sung primarily at the breeding grounds of humpbacks, presumably to attract mates, although this isn’t known for sure. Humpbacks found in the Salish Sea are more likely to be making a feeding call.

3. Gray Whale– Gray whales are rather prehistoric looking whales that can be found in the spring, summer and fall in the Salish Sea. These whales like to feed along the bottom in shallow waters, and so are frequently seen foraging close to shore. They are covered in barnacles and whale lice. These patches of parasites can help distinguish individuals.  The blows of gray whales are bushy and heart-shaped.

Gray whales also don’t have a dorsal fin, instead they have a prominent dorsal ridge.

Gray whales tend to roll on their side and scrape along the muddy bottom in search of food. Because they feed in shallow water, this often exposes their pectoral fin. They also sometimes show their flukes, which are smaller and more square-shaped than those of humpbacks.

If you wish to try to identify a gray whale that you spotted, check out the gray whale ID guide from Cascadia Research Collective.

The vocalizations of gray whales are typically series of grunts. The average frequency is typically around or below 1 kHz.

A quick comparison of these three most common species of baleen whales found in the Salish Sea:

B. The Odontoceti, or toothed whales

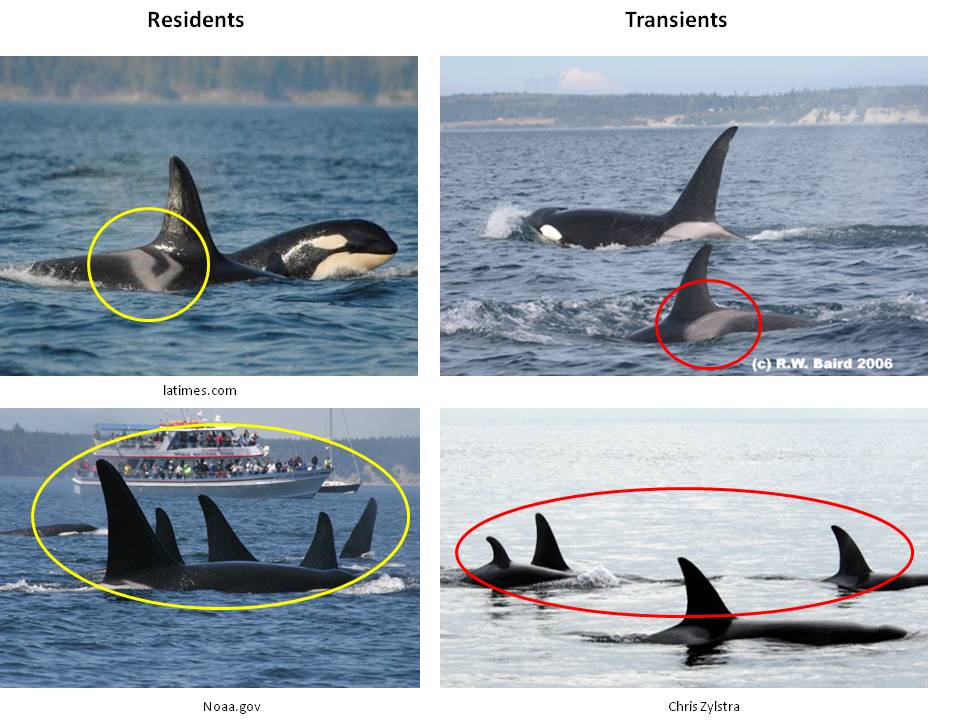

1. Killer Whale, or orca- The orca is the most easily distinguished cetacean in the Salish Sea. Actually the largest member of the Dolphin family, the orca can be recognized by it’s black and white color pattern. Males sport dorsal fins up to six feet tall, while females have smaller, curved dorsal fins. The gray saddle patch behind the dorsal fin can be used to identify individual killer whales.

Of the three ecotypes of killer whales (residents, transients, and offshores), only residents and transients are found with any regularity in the waters of the Salish Sea. While it can be difficult to distinguish these two, it is not impossible. The southern residents (SRKWs) are found in relatively large, stable family pods, while transients are typically (but not always) found in smaller pods. Of course, the SRKWs eat only fish, while the transients prey on marine mammals. So if you see a killer whale pursuing a sea lion or other mammal, it is a transient. Transients and residents can also be distinguished by their dorsal fins and saddle patches. The SRKWs have more rounded dorsal fins than transients, and they can have open saddle patches, while the transients have solid gray saddle patches. Residents and transients can also be distinguished by their calls. Residents are much more vocal, and tend to have an almost up-beat, bubbly sound to their calls. Transients typically make fewer vocalizations that have a rather haunting quality to them.

2. Pacific White-sided Dolphin- While Pacific white-sided dolphins aren’t seen frequently in the Salish Sea, they are seen at times during the summer and fall. These dolphins are relatively small, around eight feet long. They have a dark upper body, with a light underside and gray stripes running along their sides. They also tend to show more of their bodies when surfacing than the porpoise species found in the Salish Sea. They make high frequency, whistle-like vocalizations.

3. Harbor Porpoise- Harbor porpoises are small members of the Phocoenidae family. They are gray-brown on top with a light underside. They have a triangular fin. Harbor porpoises are often seen in fairly shallow water, and can be found around the mouths of rivers. They are typically found in small groups of less than ten individuals. Harbor porpoises typically make acoustic signals that are above the hearing range of humans, but it is possible to slow the calls down to allow humans to hear them.

4. Dall’s Porpoise- Dall’s porpoises have a black and white coloration that is similar to that of orcas, leading to them occasionally being incorrectly referred to as baby orcas. Measuring around 6 feet, the lack of an eye patch and shape of the dorsal fin immediately give the animal away as being a Dall’s porpoise rather than an orca. Dall’s porpoise are very fast cetaceans, and often create a “rooster tail” of spray when bow-riding. They have a small white patch on their triangular dorsal fin, helping to distinguish them from harbor porpoises. They are stockier than harbor porpoises, with a narrow, distinct peduncle (area immediately in front of tail). Like harbor porpoises, Dall’s porpoise produce acoustic signals that are too high for most humans to hear. However, when brought down to a frequency within our hearing range, they make a series of click-like sounds. Scripps Whale Acoustic Lab has a nice recording of a Dall’s porpoise here (For whatever reason I can’t link directly to it, so click on Porpoises, Dall’s porpoise, and then play call).

Comparison of toothed whales found in the Salish Sea:

Well that about wraps it up for the cetaceans of the Salish Sea! I hope that this helps provide a guide for identification of the cetaceans in this area.

Well that about wraps it up for the cetaceans of the Salish Sea! I hope that this helps provide a guide for identification of the cetaceans in this area.

On a quick side note, I would like to thank everyone who was on the Gato Verde with us this past week, and give a special thanks to Val and Leslie for cooking us a fantastic Easter brunch and letting the Easter Bunny into S1 to hide chocolate eggs for all of us!

Also, while writing this blog post, I was interrupted by orca calls on the Lime Kiln hydrophones. Carlos was super nice and drove us all down to Lime Kiln, where we got our first sighting of J Pod!!! It was extremely exciting, probably one of the best days of my life. One whale even breached right off shore from us twice! I’d like to leave you all with this photo of a whale porpoising by us at LK. Jeanne was also watching from shore; she got some IDs and posted a recording of the calls on her blog!

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook