This afternoon I’m giving a talk at the 2014 Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference in which I present our estimates of sound pressure levels from commercial ships in Haro Strait, the core of the summertime critical habitat for the Southern Resident killer whales. I also take a first look at noise impacts of the current tanker and bulk carrier fleets and ask how those impacts may change if a suite of proposed fossil fuel export facilities are added to the Salish Sea.

For this talk, I’m excited to have experimented with in-browser HTML5/CSS methods of presenting (alternatives to Power Point and Prezi). There are a bunch of interesting new players like SlideCaptain (good for equations), but I settled on Emaze because of how gracefully it handled embedding of sound and video.

Read More

Sponsored by the Puget Sound Partnership and organized by Orca Network, the Salish Sea Association of Marine Naturalists, and The Whale Museum, this workshop preceded the 2014 Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference.

Daniel Schindler, UW

The “Effects of salmon fisheries on SRKW” report

12:09 Starts with introduction of the science panel members

12:12 We were charged with evaluating the BiOp’s “chain of logic linking Chinook salmon fisheries to population dynamics of SRKW”

Population decline in both NRKW and SRKW was coordinated in late 1990s.

We were blown away by the quality of SRKW demographic data. This is probably one of the best-studied wildlife populations in the world.

Eric Ward estimated growth rate (lambda) as 0.99-1.04 (mean ~1.017, or ~1.7% exponential growth) for J/K pods and 0.985-1.035 (mean ~1.01, or ~1% exponential growth). The overall SRKW rate of 0.71% per year might increase to ~1%), but fisheries management changes are unlikely to raise the growth rate to the recovery goal.

There are 1000s of papers about Chinook salmon, but less is know about Chinook topics relevant to SRKWs. Listed 3 shortcomings.

Kope and Parken summarized Chinook trends for specific stocks important to SRKW. Coastwide there has been a modest decrease in recent pre-harvest Chinook abundance. There isn’t much room to lower commercial fishing in a meaningful way (e.g. decrease harvest of 20%).

Correlations between SRKW vital rates and Chinook abundance depends on abundance measure chosen. Mortality of SRKW should scale non-linearly with salmon abundance, but the existing correlations are linear.

12:38 Questions

Bain: Why weren’t acoustics impacts of fishing vessels considered? A: I don’t know. Perhaps because available data did not include fishing boats.

Felleman: Were analyses done using only Columbia Chinook? A: No, but you should email Eric Ward about that. You should also be careful about interpreting correlations as causal relationships. If you look for correlations from 50 different salmon populations, you’ll find strong ones just through random chance.

12:50

Elizabeth Babcock, NOAA

The intersection of salmon and orca recovery

Focus is on Puget Sound stocks. Locally-developed recovery plans for Puget Sound Evolutionary Significant Unit (14 watersheds from Neah Bay to Point Roberts; 22 populations) reviewed in 2005, then adopted plan in 2007, and are now implementing with partners.

70% of our estuary habitat area in Puget Sound have been lost…

13:00

Lynne Barre, NOAA

13:10

Mike Ford, NOAA

Salmon recovery and SRKW status

Noren (2011) suggest SRKW metabolic demand is 12.6-15.1×10^6 kcal/day =~1000 Chinook salmon/day

Ward looked at all available Chinook time series and found many correlations, including between runs, but the strongest correlations were not with the Fraser nor the Columbia.

Interesting population projection figure from Ward (2013)

Post-workshops we have been looking at trends in other marine mammals: AK and NR KWs increasing, CA sea lions now ~6x 1975 levels, harbor seals 6-8x…

Overview of salmon status

- Historic Chinook salmon abundance figure (compiled Jim Myers, NWFSC): Biggest reductions were in Columbia (~-3-5x) and Central Valley (~-3-4x)

- Bonneville time series (1938-2014) shows abundance declines happened a long time ago (pre-dams!). 2014 levels approaching 1888 average levels!

- A lot of the historical losses are due to extirpations (Gustafson et al., 2007): biggest extinct populations were in Columbia above Grand Coulee and Snake

- Run timing changes: Columbia example — ~10x reduction in interior run (above Bonneville) from ~2.5 million to ~200k.

- Hatchery production rose from 1950 to peak in mid-80s and in 2000 was near 1970s levels (Naish et al. 2007)

- Puget Sound historical abundance is ~700k (based on cannery pack in 1908); current wild escapement is ~50k; hatcheries add ~300k.

Recovery activities

- Habitat: 31,000 projects completed at 51,000 locations throughout Pac NW. Over $1 billion spent on restoration to date.

- Hatcheries: overall reductions in hatchery releases in last few decades, and limiting genetic impacts on wild fish. One example of reductions to near zero is on OR coast…

- Harvest: easiest to change and responsive; examples of successful catch reductions are Hood Canal summer chum. Coastwide harvest % has decreased by ~factor of 2 over last 30 years

- Hydro: improved fish passage, predator control, spill, barging; dam removal on Elwha, Condit, Rogue, Sandy, Hood River

- Heat: potential effects of climate change mostly not great for salmon; summarized by Stoute et al. 2010 and Wainwright and Weitkamp in prep

Budget comparison

- Orca recovery spending: FY12 1.2M on science/research; ~300k on management/conservation

- Orca salmon spending: FY12 600M!! Columbia only is 450M!

1:40 break

David Troutt, Director of Nisqually Natural Resources (for 35 years) and Chair of SRC (=Salmon Recovery Counci)

WA State salmon recovery — How we work together

2:02

State broken into regions, each with their own recovery plans (developed through the “WA way” involving many stakeholders, endorsed by Feds). Go to RCO web site for more information.

Study completed in March 2011 estimated costs of all planned regional plans is ~$5.5 billion. Funds dispersed through Salmon Recovery Funding Boards established in 1999. Funds come from PCSRF and others… Note: it is a LOT cheaper to protect than to restore…

10% of Federal grants must be used for monitoring. Example: About 80% of Nisqually outgoing smolts remain in estuary; 20% seek pocket estuaries elsewhere, but we see almost no returns of fish using the latter strategy.

There is a problem with marine survival in Puget Sound. We see 95% mortality of tagged out-going smolts between the Nisqually and Port Angeles. We’re confident that the estuary is in much better shape and 77% of the mainstem is in permanent stewardship, but we’re not seeing any result in the numbers of returning adults!

2:15 Tribal perspectives

Story: a generation of Nisqually fishers have never caught a steelhead. Annual catches of ~2k by tribes and ~2k by recreational fisheries collapsed (in 1990s?) to total run of ~500, a condition which persists. The treaties have not been withheld (and the tribes have not “shot at y’all in a long time”).

We need to work together towards ecosystem restoration. The tribes are interested in actions related to all H’s. The tribes have been working with the State to adapt how we run hatcheries to support harvest, but also be consistent with recovery goals. The North of Falcon process is part art, part science, but it is transparent and it works.

Rich Osborne, North Pacific Coast Lead Entity Coordinator (WRIA 20)

WA Sustainable Salmon Partnership — Salmon recovery on the WA coast

2:25

What’s unique about the outer coast in terms of salmon restoration?

- All 5 salmon species and steel head; none are listed except Ozette sockeye.

- Large areas are encompassed within tribal lands, which allows alternative restoration strategies.

- Almost no people! Only 7000 people on coast with no residential areas

- Large portions of watersheds in National Park, other large areas in National Forests.

Formed a non-profit to raise money beyond the SRFB: the WA Coast Sustainable Salmon Foundation. WRIA 21 = Quinalt; WRIA 22&23 Grays Harbor; WRIA 24 Pacific County.

Example projects:

- Goodman Creek road decommissioning (4 miles of road and fill removed)

- Quinalt: old logging road and fish passage blockage removal — facilitated by ability for tribe to control local decisions.

- Grays Harbor: huge estuary Chehalis has spectrum of impacts (industrial, logging, headwaters in National Park), but again not many people

- Pacific County (Willapa Bay): huge estuary w/few people; mostly Weyerhauser timber operations between pristine upper watersheds and the ocean.

28 Chinook stocks returning only 30-40,000, but could be 100s of 1000s…

An additional 12 million hatchery fish released from coastal watersheds per year

Salmon stronghold study areas (circa 2006)

Jeannette Dormer, Puget Sound Partnership

Salmon Recovery in Puget Sound

2:45

In contrast, there are 4.1 million people in the Puget Sound region: 12 counties, 20 large cities, 100 cities total, 17 treaty tribes, many NGOs; 15 lead entities; Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Council (not the Partnership) is policy body to oversee implementation of the PS salmon recovery plan.

6 salmonid species, 3 listed under ESA (PS Chinook threatened in 1999, Hood Canal summer chum threatened in 1999, 2007 Puget Sound steelhead).

Salmon recovery success example: Puget Sound Acquisition & Restoration (PSAR) Fund. Regional priority list; increased from $15 million to $70 million appropriated for 2013-2015 biennium

- 100s of acres of estuary restoration in Snohomish and Skagit rivers

- Elwha dry lake bed reforesting

- 3+ acres eel grass on Bainbridge

- Seahurst seawall removal and restoration

Intersection with orca…

3:05

Jacque White, Exec. Director of Long Live the Kings (used to work at P4PS and Nature Conservancy)

Salish Sea marine survival project

Many partners supporting the coordinating organizations — Long Live the Kings in U.S. and Pacific Salmon Foundation in Canada

“Puget Sound salmon are sick and we don’t know why…”

- Coho marine survival declined sharply in 1980s from ~3% to <~0.5% and has persisted, while during the same period (1974-2007) WA/BC coastal survival has been fluctuating around a mean of ~0.5%. There are similar trends for steelhead and Chinook.

- Declines in Fraser sockeye, steelhead, herring spawning areas, forage fishes, hake, lingcod

- Rises in Harbor seals, lags, temperatures, and human population

- Little effort to integrate research efforts

- Now seeing economic impacts on humans (sports fishing, tribes, First Nations)

Time line:

- 2007 State of the Salmon in 2007 focused on interactions of wild and hatchery salmon

- 2012 fall workshop led to idea of a transboundary project to increase survival in the Salish Sea, improve accuracy of adult return forecasting, and assess success (or failure) of existing salmon recovery efforts.

- 2014 Comprehensive planning

- 2015+ Implementation of research

Hypotheses (trying to identify factors that control salmon and steelhead survival that can be managed)

- Bottom-up processes (PDO, environment, forage fish changes to which salmonids haven’t been able to compensate)

- Top-down (predation…)

- Other factors (toxics, disease…)

Research activities

- Focus on juvenile fish

- Predation of seals on steelhead

3:45 break

Panel discussion (audio recording: .ogg [~68 Mb] | .mp3 [~34 Mb]; responses are hard to hear for some panelists who did not use microphones)

3:58 Begin

5:14 Final comments and next steps (also included in audio recordings)

Read More

The year 2013 was an exceptionally unusual one in the world of southern resident killer whales and Pacific salmon. Most noticeably, the southern residents returned to the Salish Sea later than normal, raising concerns among conservationists. Throughout the summer, researchers and whale watch operators noted that the whales were present less than normal and the duration of their visits to the Salish Sea were abbreviated.

Meanwhile, the Chinook salmon runs on the Fraser plummeted while 80-year record returns were counted on the Columbia at the Bonneville dam fish ladder. Combined with new evidence from satellite tags that the southern residents are focused on Columbia salmon during the spring months, the sighting patterns of 2013 may indicate a transition for the urban estuary known as the Salish Sea — from one with “resident” orcas to one with southern “transient” fish-eating orcas.

Killer whale trends

Based on data from the Orca Network sighting maps from the past decade (see figure below), records were set or tied in 2013 for the least number of days spent by southern residents in the historic core of their summer habitat (the west side of San Juan Island in Haro Strait). The SRKWs were seen only once in March and not at all in April. Even more shockingly, they showed up only 5 times in May (a record low) and were observed 15 times in June, a low level not seen since 2001.

The same data show downward trends in monthly sightings over the last decade. With the exception of a high in 2011, the March prevalence has been flat or decreasing. There are stronger, more continuous downward trends in April and May sightings.

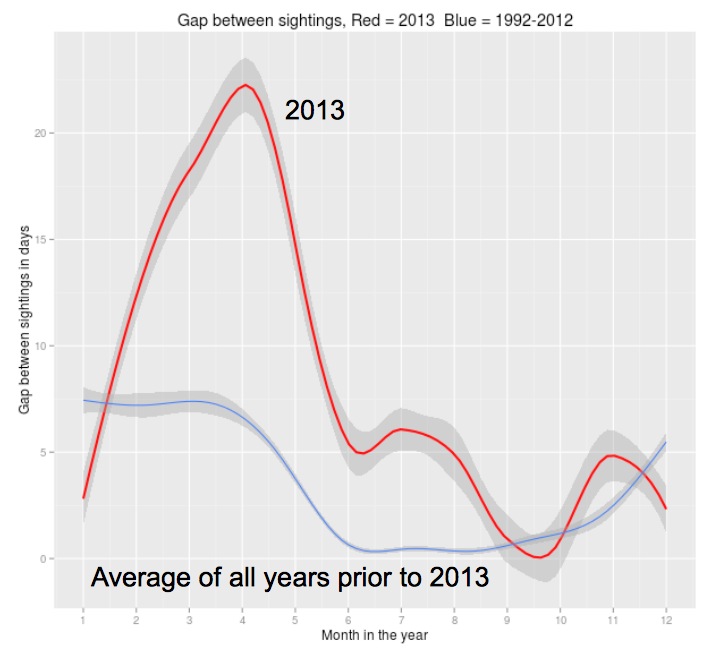

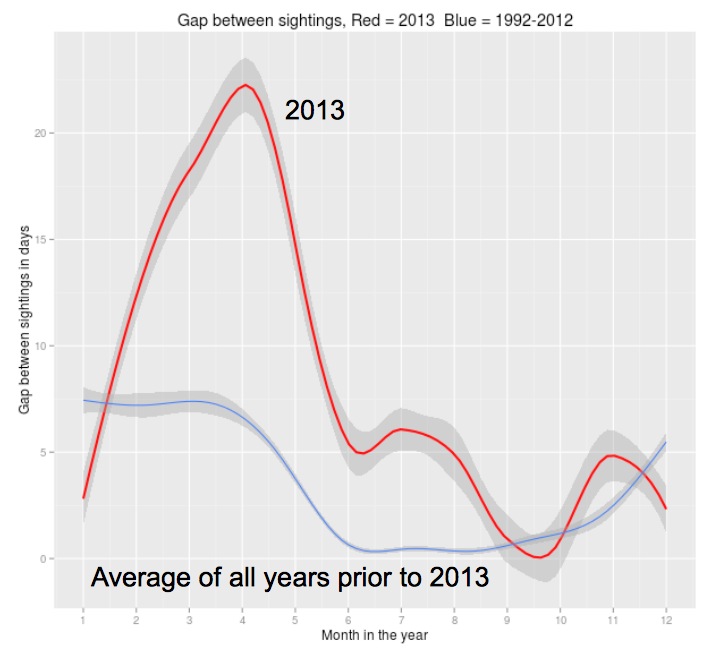

We used the OrcaMaster database maintained by The Whale Museum to look for trends in sighting “gaps” — the number of consecutive days between sightings of J pod members within the Salish Sea.  Val plotted running averages of 2013 gaps versus a historic average (1992-2012) and found that in the spring of 2013 sighting gaps were 2-5x longer than the average. Only during and after September of 2o13 did the gap return to a normal duration. (Maybe we should look at trends in Salish Sea chum run?)

Historic trends in J pod sighting gaps (Val Veirs, using R and ggplot)

Chinook trends

One way to characterize the foraging conditions the SRKWs experienced in 2013 within the Salish Sea and on the outer coast is to examine the Chinook salmon counts from the Fraser and Columbia rivers. The Albion test fishery on the Fraser provides a proxy for the abundance of Fraser Chinook, the primary prey of SRKWs in the Salish Sea from spring through the summer (Hanson, Baird, Ford, Hempelmann-Halos, Van Doornik, Candy, Emmons, Gregory Schorr, Brian Gisborne, Katherine Ayres, Samuel Wasser, Kelley Balcomb-Bartok, John Sneva and Michael Ford, 2010). The fish counts at the Bonneville dam on the Columbia are a proxy for the abundance of Chinook on the outer coast of Washington.

As marine naturalists like Jane Cogan and Monika Wieland have pointed out, 2013 was an exceptionally bad year for Fraser Chinook returns. The fish arrived late and the cumulative returns were well below this historic average and only slightly better than in the worse year on record, 2012. The highpoint of the 2013 run was the peak around the 3rd week of August that may also be related to a pulse of Chinook recorded in the first two weeks of July off southern Vancouver Island (in the Area 20 test catch fishery).

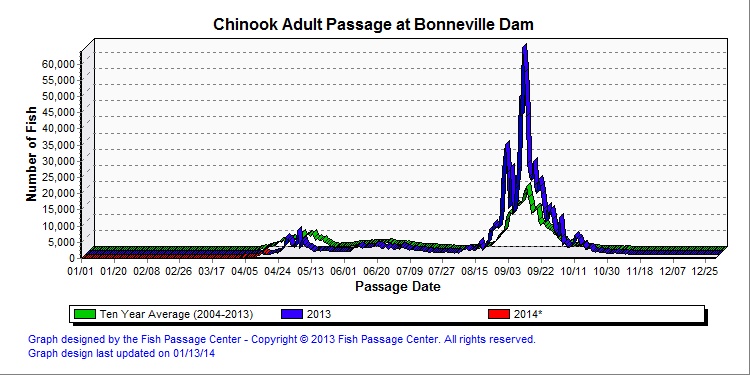

In contrast, adult and jack Chinook abundance in the Columbia River has been on the rise for the past couple decades, with 2013 standing out as a record-setting year for adult Chinook.

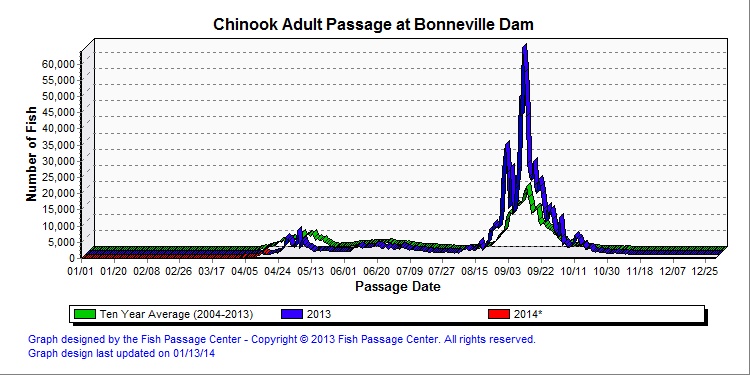

Daily Chinook counts at Bonneville show that while most of the record-setting abundance was due to the fall run, the spring run also had peaks well above the 10-year average.

Daily Chinook counts at Bonneville show that while most of the record-setting abundance was due to the fall run, the spring run also had peaks well above the 10-year average.

The spring run passed Bonneville from late April to late May, 2013. This timing is consistent with the timing of the spring Columbia Chinook run in 2012. Since Bonneville dam is about 200 km upstream from the river mouth and adult Chinook swim at about 0.5 m/s, we could expect that the returning Columbia Chinook were in the ocean at least until about a week before they reached Bonneville ( 200,000 m / 0.5 m/s = 400,000 seconds = ~5 days). So where were the southern residents in March and April of 2013, since they weren’t being sighted in the Salish Sea? We don’t know about J and L pods, but the satellite tag deployed on K25 indicates the likely position of K pod (up until April 4).

The answer is: during March, 2013, K25 was spending a lot of time going back and forth along the continental shelf of Washington (and to a lesser extent Oregon) with a track that centered on the mouth of the Columbia River.

We need to know more about when the returning Columbia fish are on the continental shelf and accessible to the southern resident killer whales. But these salmon trends from the region’s biggest rivers combined with migratory patterns of the orcas strongly suggest that the southern resident killer whales may be happy to move their “residence” to wherever the eating is best! Perhaps we are watching them become southern transient fish-eating killer whales?!

Anecdotal observations of orca-salmon interactions

When the fish-eaters were around during the summer of 2013, they displayed some unusually aggressive foraging. A (potential) prize Chinook salmon was taken off a derby fisherman’s line and became the focus of a KPLU radio story and an impressive photo of the one that was eaten away…

The part that didn’t get (taken) away. (credit: Kevin Klein)

This local predation event was a first for Washington State (as far as we know), though it was comparable to one by Alaskan fish-eating killer whales. In the video below, the Alaskan whales were foraging amongst fishing vessels and happened (probably visually) upon a large hooked Chinook. (Mute your speakers if you don’t want to hear angry and amazed fishermen cursing.)

Later in the summer of 2013, back in Washington, a whale watch captain obtained this video of southern resident killer whales pursuing a large (likely Chinook) salmon alongside the boat —

Could these uncommon foraging observations indicate that the southern residents were having a tough time finding enough to eat in the Salish Sea? We’d be interested in hearing from local fishers about how often they’ve had fish taken off their lines by Southern Residents. Monika assures us though that it is common to observe SRKWs pursuing salmon around and underneath whale watching boats, so maybe we should attribute the second video to more typical foraging and take it as evidence that orca-salmon interactions in the fall of 2013 were more typical than earlier in the year.

7919

{5THBC54C}

apa-no-doi-no-issue

default

ASC

no

5175

http://www.beamreach.org/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

Hanson, M. B., Baird, R. W., Ford, J. K. B., Hempelmann-Halos, J., Van Doornik, D., Candy, J., … Michael Ford. (2010). Species and stock identification of prey consumed by endangered southern resident killer whales in their summer range. Endangered Species Research, 11, 69–82.

Read More

Southern resident line up. (credit: Center for Whale Research)

A couple years ago Val put a bunch of effort into stabilizing a video of some rare southern resident killer whale behavior that Beam Reach observed during our first field program in fall, 2005. In support of an upcoming fundraiser for The Whale Museum, we have uploaded the stabilized version to YouTube and then stabilized it as second time using YouTube’s editing enhancement. (The original, shaky footage is also stabilized as of 2014, but only using the secondary YouTube stabilization.)

We hope the double-stabilized version (embedded below) doesn’t make you too seasick. You may also enjoy the links below and appended background information re-posted from what was originally published at orcasphere.net.

Stabilized video

Video credits go to Beam Reach students Brett Becker and Courtney Kneipp. Still photo credits go to the Washington State Department of Ecology and Iris Hesse of the Center for Whale Research. Listen for a very unusual simultaneous call made by many individuals during the last minute of the recording.

Related links

Originally posted on May 16, 2006 —

One of the most remarkable behaviors of the southern residents is the “greeting ceremony†in which two groups of orcas line up facing each other and then mingle together. This article describes a similar “ceremony†acoustically and visually (video; photo gallery), and then discusses whether it may have been related to a “greeting,†a “goodbye,†or a more complex combination of activities.

I offer it here in the hope that others who witnessed this particular event may further consider what occurred. Please feel free to comment on this article and/or contribute your thoughts via the discussion forum. Insights from other accounts of different “ceremonies†performed by the southern resident (or other) orcas would also be welcome. Perhaps we will piece together a publishable story?

On October 4, 2005, only a week into a month of sailing with the southern residents, students and teachers of the Beam Reach marine science and sustainability school approached San Juan Island along with members of J and L pods. The Beam Reach research vessel, the sailing catamaran Gato Verde, paralleled the orcas as they moved northward from Salmon Bank along the west side of San Juan Island during the mid-afternoon. In the early evening, starting around 4:30pm PST, the pods began to concentrate within 100 meters of shore below Hannah Heights.

The “ceremony†that we observed (along with Tom McMillen, observers from the Center for Whale Research, and Sharon Grace [and others?]) was similar to “greeting ceremonies†that sometimes occur in the spring as the southern residents return to the Salish Sea from their winter ranges. One group of at least 9 adults and one calf (probably a subset of the group that had been traveling northward with us) congregated within 100 meters of shore ~0.5km southeast of a promontory with abundant driftwood (48o 29.65N, 123o 7.62W). They remained on the surface, gathered into an extremely tight group, traversed the shoreline southward for a few minutes, then doubled back to the north. Meanwhile, a different group of at least 9 adults rounded the driftwood point, heading south, and began to congregate in a rough line just south of the promontory’s rocky bluffs. They, too, remained largely on the surface, drew together in a line, and proceeded slowly southeastward toward the southern group. When they were about 25m apart, the southern group lunged forward, submerged, and quickly met the northern group. The two groups mingled, turning quickly and making brief dives, and remained together for an extended period (at least 15 minutes — we left at ~5:15pm to make port before nightfall — and probably much longer).

The ceremony was documented by Beam Reach with still photographs, digital video, and stereo underwater sound recordings. Preliminary analysis of the still photographs and video suggests that at least J40, J14, and L41 were part of the southern group. Tom McMillen of Salish Sea Charters with Iris Hesse and EEH (??) of the Center for Whale Research (CWR) were drifting near the northern group and photo-identified many of its members. Based on an initial examination of still photographs taken of the combined groups, Dave Ellifrit of the CWR noted that L84, L41, L90, L72, L55, L82+calf, L25 with L41, and Raggedy (K40) were present. Any additional photo-identification (and associated) debate is welcome!

An interesting aspect of this event, first pondered by Tom McMillen (and later discussed with Ken Balcomb and Dave Ellifrit?), is that it approximately coincided with the last time that the matriarch L32 was seen. Earlier in the day (about an hour before the ceremony began?), Tom observed L32 with son L87 and noticed that she was emaciated and had a weaker-than-normal blow. CWR photographs confirm that L32 had a sunken blowhole area (“peanut headâ€) that day. L32 was not observed after the ceremony and L87 was observed the next day (or maybe 2 days later?) without L32, so L32 is now presumed to be dead. Could we have witnessed a “goodbye†ceremony?

Perhaps, but the CWR photographs reveal that the ceremony also involved foraging (birds hovering over orcas at surface) and sexual activity (sea snakes). Beam Reach video shows traveling behavior, milling, tail lobs, and pectoral fin slaps. There was a lot of acoustic activity prior to the meeting of the two groups, including abundant echolocating and intermittent calls, and an amazing coordinated acoustic event in which many individuals call simultaneously (without an obvious cue).

I’ve created this movie that juxtaposes the best of the Beam Reach video and underwater sound. Please note, however, that I was unable to synchronize the sound and video. I am tempted to associate the simultaneous calls with the dynamic lunge of the two groups together, but (I regret) there is currently no way to know whether that is right. Video footage was acquired by Beam Reach students Brett Becker and Courtney Kneipp. Acoustic data is from 2 ITC hydrophones mounted 1.4m apart on a horizontal pipe at 4.4m depth. (The engine noise at the beginning of the movie is from the Beam Reach research vessel.)

Please don’t hesitate to comment, email, or start a discussion thread if you have information or ideas about this fascinating behavior of the southern residents.

Read More

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook