Could Naval activities threaten orca recovery?

What killed L-112/Victoria/Sooke? (Photo courtesy of Ken Balcomb, Center for Whale Research, copyright 2013)

The short answer for citizens of the U.S. West Coast and British Columbia is yes. In the course of training to keep our coastlines and cities safe, one of our Navies could accidentally blow up the southern resident killer whales (SRKWs), cause them to strand, or deafen them to the point of being unable to locate their favorite food — scarce and contaminated Pacific salmon.

The long answer is we don’t know yet.  We have not yet been able to rule out the possibility that a 3-year-old female resident orca known as L-112 was killed this month (February, 2012; born Feb, 2009) by military sonar or an underwater explosion. Excluding such possibilities is important, in part because it would increase the likelihood that the dead female’s close relatives will return unharmed this summer, and that the SRKWs will return unscathed in future summers.

What is clear is that in February 2012 we experienced a sequence of events that should motivate us all to understand the potential risks of generating loud noises, particularly during military activities, in the habitat of marine animals that we value and that rely heavily on sound for their survival. Until we have divorced our military training and testing areas from the critical habitat of the SRKWs, and mitigated potentially harmful sources of underwater sound with attention to their annual migratory patterns, we will continue to run the risk of SRKWs suffering the type of acoustic trauma that may have killed L-112.

In this post, which remains a work in progress as of the most recent edit (8/13/2018), Beam Reach students and staff along with our collaborators aspire to review the facts of the L-112 case and assess to what extent they are causally connected. Along the way we catalog the history of military training and testing — both within the inland waters and on the outer coast of Washington — with an emphasis on acoustic observations we have helped obtain in the Salish Sea. We keep notes on what we know, what we need to know, and how hard it is to know enough to definitively connect (or disconnect) the use of military sound sources like mid-frequency active (MFA) sonar or underwater explosions with marine mammal hearing threshold shifts, changes of behavior, strandings, injuries, and deaths.

A remarkable sequence of events in February, 2012

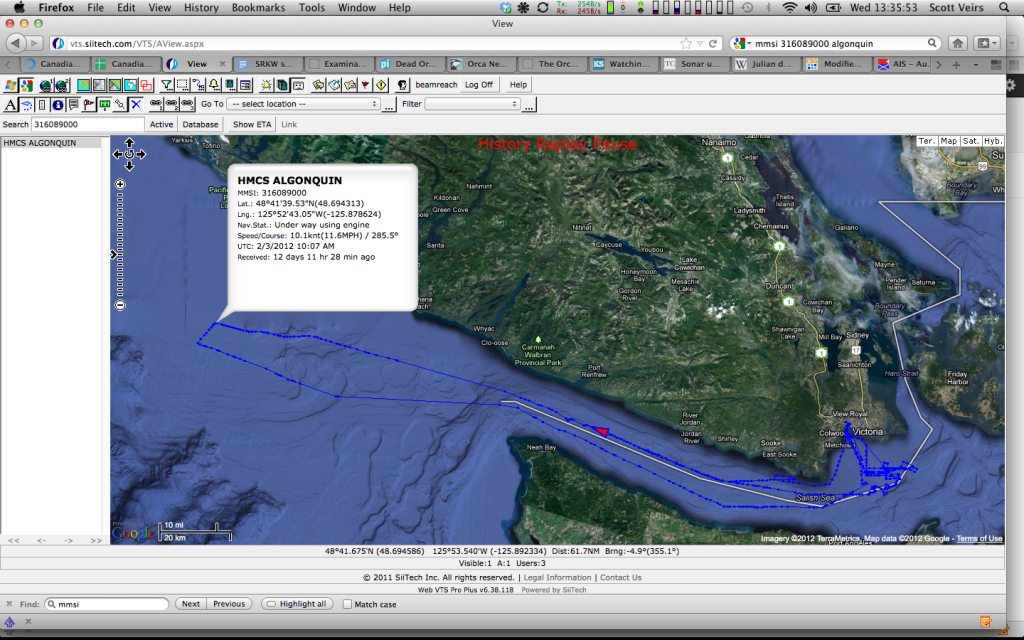

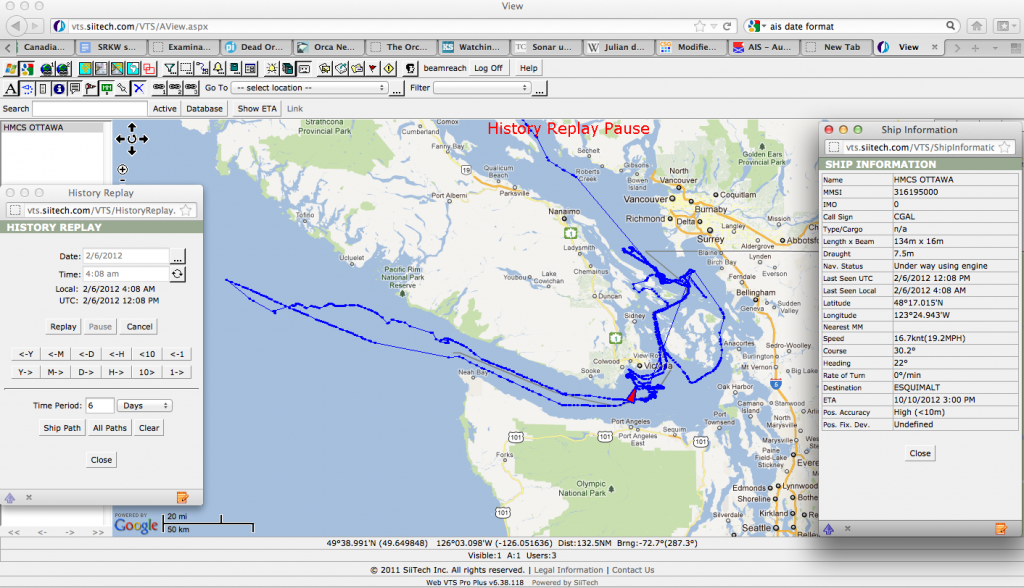

On Thursday, February 2, 2012, the Canadian frigate HMSC Ottawa traversed the continental shelf off of southwest Vancouver Island along with another Canadian Naval vessel, the destroyer Algonquin, that also carries the SQS-510 mid-frequency active (MFA) sonar system. Based on AIS data from the ships themselves, the Algonquin returned into the Strait of Juan de Fuca within about 12 hours, while the Ottawa continued into the Pacific where (we assume) it remained until it returned to the Salish Sea and utilized its sonar on 2/6/12.

On Monday, February 6, 2012, the Canadian frigate Ottawa uses sonar in the critical habitat of the SRKWs. The Canadian Navy confirmed that this inland training exercise (NW of and within the Strait of Juan de Fuca, as well as Haro Strait) involved underwater “DM211” detonations underwater sounds recorded by the Salish Sea Hydrophone Network in Haro Strait just minutes before the first sonar pings were detected.

On Saturday, February 11, 2012, a 3-year-old female member of the SRKW L pod known as L-112 is found dead on the beach just north of the Columbia River mouth. This occurs 9 days or 5 days after the previous events.

View 2012 sonar and L-112 stranding in a larger map

Detailed chronology

Bracketing these events are the rare sightings of SRKWs and rarer opportunities to identify pods and individuals. While SRKWs are normally only seen once or twice a month in the winter, some combination(s) of L and K pod were heard in the vicinity 18 hours after the sonar use and observed 36 hours after the sonar event for the first time ever deep within Discovery Bay.

As we gather the details of who was seen where and when, we will summarize them in the following chronology and document the evidence for each entry in the body of this post. In the chronology (a Google spreadsheet to which you may also contribute), the red background denotes sonar events, the orange background denotes potential explosive events, the blue background is for marine mammal observations, and white background is for ship locations and other events.

Outline of lines of evidence

As we explore the available and emerging lines of evidence, we will update the chronology as we document what is known in the following sections of this blog post:

- Pre-February distributions of SRKWs and other species of concern

- Feb 2-5 — Offshore Naval activities

- Pre-sonar(s) locations of SRKWs and other species of concern

- Feb 6 — Ottawa use of sonar in the Salish Sea

- Post-sonar locations of SRKWs and other species of concern

- Feb 11 — Discovery of L-112 remains, hypotheses regarding the cause of death, and subsequent findings

- History of sonar use and other military activities in Washington State

Pre-February distributions of SRKWs and other species of concern

The majority of L pod was last seen in November (?), 2011

Feb 2-5: Offshore Naval activities

Sometime during the daylight hours of Thursday, February 2, 2012, two Canadian Naval vessels began activities which remain unexplained a month later (as of 3/6/12). The destroyer Algonquin, leading the frigate Ottawa by about 20 minutes, made its way out through the Strait of Juan de Fuca about 2/3 of the way across the continental shelf and then made a U turn. The Algonquin returned to the Salish Sea while the Ottawa headed out into the Pacific (see AIS tracks below and chronology above).

Importantly, the Ottawa’s was out in the Pacific (beyond the range of coastal AIS receiver stations) for 2.75 5 days (2/3/2012 3:42:00 through 2/5/2012 21:14:00). Where was this frigate during that period? We don’t know, but at typical to max speeds of 15 to 25 knots it could have made an excursion of 500 to 800 nautical miles into the Pacific — as far south as the Oregon-California border, or as far north as central Haida Gwaii.

What was the frigate doing in the Pacific? We don’t know, but upon its return it engaged in sonar training, possibly preceded by some sort of underwater detonations…

Were U.S. Naval ships in the same region operating sonar or engaged in generating explosions during the same period?

In a blog entitled “So far, sonar has not been linked to orca death“Â Chris Dunagan of the Kitsap Sun reported:

I have been in touch with both U.S. and Canadian Navy public affairs officials, and both have denied that their ships were using sonar in the ocean during this time.

We should not forget to also ask carefully about any and all other Naval activities (e.g. sonar use by other entities, or potential sources of explosions), as well as other possible sources of intense underwater noise (e.g. seismic exploration).

Indeed, we should seek at least:

1) a clear explanation of what the Ottawa did do when it was in the Pacific; and

2) a confirmation of whether or not the Ottawa may have been operating in the same part of the ocean as L-112, particularly when she was killed.

Pre-sonar(s) locations of SRKWs and other species of concern

Amazingly, the calls commonly made by J pod are audible in recordings made by the NEPTUNE Canada “upper Barkley slope” hydrophone located on the outer continental shelf at the same time that the Ottawa was returning from the Pacific, steaming into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, en route to its home port of Esquimalt (just west of Victoria, BC). Searching the NEPTUNE archives for recordings made as the Ottawa passed overhead (based on its AIS transponder data) revealed a period of the recordings in which all information below 6kHz had been filtered out (by the U.S. or Canadian Navy). Near the end of the filtered data, southern resident killer whale calls are audible — even though only the harmonics extend above the high-pass filter at 6kHz.

(2018 questions: What calls were made and are there any hints that L pod individuals were with J pod at the time? Could this same group have been inbound and ended up (taking refuge?) together in Discovery Bay 36hrs after the Constance Bank military exercises?)

For now, here’s an example taken from just after the filtering ceased —

NAXYS_02345_P008_20120206T082327.995Z

This suggests the Ottawa may have (or should have?) known that SRKWs were near the entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca just a few hours before they began using their sonar in the eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca. Yet, Dunagan quotes the Canadian Navy (bold emphasis added):

Lt. Diane Larose of the Canadian Navy confirms that two sonar-equipped Canadian Navy ships, the HMSC Ottawa and the HMCS Algonquin, were out at sea before entering the Salish Sea at the time of Exercise Pacific Guardian. But neither ship deployed their sonar before reaching the Salish Sea on Feb. 6, when Ottawa’s pinging was picked up on local hydrophones, she said. Navy officials say they followed procedures to avoid harm to marine mammals and have seen no evidence that marine mammals were in the area at the time.

Had they heard any evidence that marine mammals were in the area? And what’s the “area” we’re talking about?

The following video from CTV Vancouver Island cites an email from the Canadian Navy to CTV News as stating that “Those tests [visual observations?] were done in early February and ‘There were no reports, nor indications of marine mammals in the area’.” It also includes brief quotes by Commander Scott Van Will (“….We’ll be able to [use sonar to] detect them [whales] as well.” [!]), Anna Hall, and Lt. Larose.

Feb 6: Ottawa use of sonar in the Salish Sea

Please begin by reading the post at orcasound.net for details about the Ottawa’s use of sonar, including sound recordings made automatically and by human listeners.

An unanswered question (as of 3/13/2012) is what caused the impulsive, reverberant sounds that were automatically detected and recorded on 2/6/2012, first at Orcasound at 4:31:05, then 4 times at Lime Kiln until 4:39:07. These sounds were recorded just 3-12 minutes prior to the first auto-detected sonar ping, but the Canadian Navy has not confirmed or denied they were associated with the Ottawa sonar training exercise. No impulsive sounds were auto-detected at those times (+/- 10s of minutes) at other regional hydrophones (Port Townsend, Neah Bay, and the NEPTUNE Barkley upper slope hydrophones.

Post-sonar locations of SRKWs and other species of concern

18 hours after the Ottawa’s use of sonar in Salish Sea, the calls commonly used by K and L pods were heard in Haro Strait.

36 hours later a group of K and L pod whales was sighted deep in Discovery Bay — where Southern Residents had never before been seen in ~40 years of recorded observations.

(2018 questions: Were any photo-IDs made of the L pod individuals at this time, or subsequently, that could determine if L-112 was with this group or with the L pod whales making calls off Westport, WA, and Newport, OR, on 2/5/12? Do we have any data on swim speeds of injured or panicked SRKWs, or of mothers carrying their injured or dead offspring? One data point could come from J-35 carrying her newborn for multiple weeks in July-August, 2018, but how to body masses compare between newborn [fe/male?] and 3-year-old female?)

Feb 11: Female SRKW L-112 found dead

The discovery of L-112 on Long Beach, WA

The body of L-112 (Sooke/Victoria) was found on Long Beach, WA, about 15 kilometers north of the Columbia River. There is some inconsistency in the exact location reported in the initial necropsy report and media. The necropsy report states that L-112 “washed up just north of Long Beach, Washington on the morning of February 11.” King 5 reported that “Her body was found about a mile north of the Cranberry Beach approach.” A March 27th story in the Chinook Observer specified the location as “100 yards north of the Seaview approach,” but there doesn’t appear to be a Seaview approach. We interpret these reports to estimate the location of the body as 100 yards north of the Cranberry approach in Seaview, WA.

View Map of 2012 sonar event(s) and L-112 stranding in a larger map

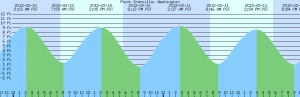

Low tide on Washington’s outer coast (as predicted for Pt. Grenville, see plot below) was at 20:13 on 2/10/12. The tidal height rose until 02:37 on 2/11/12, fell until 08:46, and then rose to high tide at 14:54. If L-112’s (buoyant) body was not observed by beach walkers during the daylight hours on 2/10/12 (sunset at 19:56) and was found before noon near the high-tide line, then the time at which she reached the beach can be constrained to be during the 12 hour period between about 20:00 on 2/10 and 08:46 on 2/11. Sun rise on 2/11 was at 06:37 so it’s possible that beach observers could further constrain the arrival time.

When on the morning of February 11 did L-112’s body reach the beach? Can anyone confirm L-112’s body was not on the beach on 2/10/12? What was the weather like the day before? (Is it likely that lots of people were on the beach then?) When was the discovery reported by who?

The videos and still photos below show that it was overcast and rainy on the morning that the body was recovered. There was no documentation of L-112’s right side when she was on the beach or on the truck due to her initial orientation which was maintained as she was winched onto the flatbed.

Video by Dave Pastor showing Keith Chandler (Marine Mammal Stranding Network) mentioning that necropsy might be performed that afternoon, as well as footage of the body being measured and Duffield calling in a request for the GPS location of the body prior to movement by the towing company —

Video by Hill Autobody and Towing —

Initial Necropsy (Feb 12, 2012)

The most mysterious part of the initial necropsy report [by Jessie Huggins (Cascadia Research), Deb Duffield (Portland State University) and Dyanna Lambourn (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife)] is the extensive internal trauma (hemorrhaging?) without mention of blunt-force trauma (no obviously broken bones):

The whale was moderately decomposed and in good overall body condition. Internal exam revealed significant trauma around the head, chest and right side; at this point the cause of these injuries is unknown. The skeleton will be cleaned and closely evaluated by Portland State University for signs of fracture and the head has been retained intact for biological scanning.

PDF of initial necropsy web page (archived 2/3/2012)

Cranial Necropsy (Mar 7-8, 2012)

Below is a synopsis of the 2-day cranial necropsy. It contains about 1-hour of highlights and significant findings. (Unedited HD footage is available from Beam Reach.)

Killer whale L-112 cranial dissection from Beam Reach on Vimeo.

Necropsy of the head of the southern resident killer whale known as L-112/Victoria/Sooke. The dissection took place at Friday Harbor Labs on March 6-7, 2012.

Progress report from NOAA (Apr 2, 2012)

An April 2 progress report from NOAA (archived in comments below) summarized L112’s injuries as “extensive hemorrhage in the soft tissues of the chest, head and right side of the body.” It also published (for the first time in writing?) a bound on the time of death: “Observations indicate the animal was moderately decomposed but likely dead for less than a week when found.” Previous estimates of the time elapsed between death and reaching the beach were in the range of 1-7 days, with a verbal estimate by Dyanna Lambourn during the cranial necropsy of 2-4 days.

Further details emerged in a June 2012 Seattle Magazine article through a quote of Jessie Huggins:

The biggest thing we found was the extent of the bruising; you could see it around the head and the chest and on the right side, and on the top of the lungs,†says Jessie Huggins of Olympia’s Cascadia Research Collective, a nonprofit that researches marine mammals. Researchers found no broken ribs and no signs of disease. “It looked like a healthy whale that had been through quite a bit of trauma,†says Huggins.

Where are photos of the right side of L-112?

Is there video footage of the gross necropsy?

(2018 questions: Can we acquire further details about the as/symmetry of the bruising on the body (not head), and more forensic information about the damage at the “top of” the lungs? Is there a formal full report from the gross necropsy?)

Subsequent findings

CT scan of head (and other bones?)

(2018 questions: did these data end up with The Whale Museum, Seadoc Society, or ??)

Cleaning of non-cranial bones

Albert Shepherd and Amy Traxler of The Whale Museum cleaned L112’s skeleton in late-February, March, and April through a combination of flensing, sea water immersion, and the dermesid beetle colony at the Burke Museum in Seattle.

The April 2 progress report stated that they had not yet found any evidence of fractures in any of L112’s skeletal bones. It isn’t entirely clear if this statement covered the cranial bones, including the middle ears. During the necropsy there was some mention of the inner ear(s) being displaced from their attachments to the middle ear.

Final Report from NOAA (Feb 2014)

Feb 2014: Wild Animal Mortality Investigation: Southern Resident Killer Whale L112 Final Report”

Hypotheses regarding the cause of death

(in order of likelihood; most-likely first)

- Primary blast injury (from a nearby underwater detonation)

- Active sonar exposure

- Ship or boat strike

- Attack by other predators/cetaceans

- Collision (e.g. with shoreline due to acoustic disorientation)

- Other noise exposure (seismic testing or earthquake)

- Disease

- Entanglement in fishing gear

- Poisoning or other ingested hazard

- Starvation

Primary blast injury

Hypothesis

L-112 was killed or deafened by an underwater detonation.

Possible causes and expected signs

- Bomb dropped into Northwest training complex of the U.S. Navy off the coast of WA.

- Underwater explosion associated with readiness training of the U.S., Canadian, or other Navies.

- Accidental underwater detonation of unexploded ordinance

- Underwater explosion from some a non-military source (e.g. seal bomb near Columbia river)

Evidence for or against

Main evidence for:

- The apparent spatio-temporal juxtpostion of L-112 and the Canadian Naval use of underwater explosives, specifically the “anti-frogman” DM211 charges.

- If L-112 was with the L-pod members heard calling off Westport, WA, and then Newport, OR, on 2/5/12, she could have been further north on 2/4/2012 when the Ottawa reports deploying at least 3 charges, some of them “in the morning” (which could mean during darkness when visual sightings were limited) “85-90 n.

- SRKW calls were recorded at the ONC Folger Deep hydrophone at the same time that the Ottawa was en route from the 2/4-2/5 DM211 detonations to Constance Bank where the Canadian Navy reported dropping two more charges on 2/6. Did the 2/4-5 detonations cause L-pod to fractionate — with one group proceeding down the WA/OR shelf and the other going inland with some members of J-pod? Where was L-112, most likely during this pre-stranding Naval training period?

- 36 hours after the Constance Bank training (2-4 DM211 detonations and active sonar use), strange mixes of L and J pod members were observed in unusual locations

- The possibility that a panicked, injured whale could swim (or be carried) from the juxtapositions of SRKWS and confirmed Naval detonations to the area of the stranding.

- List most likely juxtapositions and approximate distances to most probably path of drift

- Search for measurements of mean swim speeds for such panicked, injured, or burdened killer whales

- The consistency of L-112’s injuries with acoustic (as opposed to blunt force) trauma

- What does acoustic evidence of blast trauma look like (in other mammals)? (Look to gruesome WWII studies…)

- Find better reference for 15-yard “kill zone” of DM211 charges, and seek zones of tissue damage, PTS, TTS, etc for either humans and/or cetaceans (ideally KWs)

Main evidence against is that currents and wind suggest a dead animal would have drifted to Long Beach from the south, suggesting that transport by currents from the Naval training activities is not possible. A possible refutation of this line of reasoning is that L-112 swam some portion of the 370 km from southern Haro Strait where the Ottawa utilized explosives and sonar to the mouth of the Columbia River — the approximate point of death (based on 1-7, or 2-4 days of drift before the body was discovered).

How long would a SRKW take to traverse that distance?

- 1.7 days at 9 km/hr (~5 knots) — typical travel speed for SRKWs

- 20.5 hours at 18 km/hr (~10 knots) — possible panicked travel (porpoising) speed for SRKWs

Are there common misconceptions about (a) how quickly SRKWs move around the Pacific Northwest, and/or (b) how far it is from the Salish Sea to the mouth of the Columbia? Recent satellite tag data (2012-2015) could help build intuition and realistic models that could inform the testing of this hypothesis.

Conclusion

Active sonar exposure

Hypothesis

Possible causes and expected signs

Evidence for or against

Conclusion

Template…

Hypothesis

Possible causes and expected signs

Evidence for or against

Conclusion

History of sonar use and other military activities in Washington State

Update the Beam Reach wiki entry on sonar chronology in the Salish Sea

Add pre-2003 event(s)

Was there a previous use of sonar by the Canadian Navy?

NOTES:

Surface ducts can occur when a mixed (isothermal and isohaline) layer of sufficient depth exists. Because the speed of sound in sea water increases with pressure, a sound of high-enough frequency made within the mixed layer will become trapped in the layer instead of spreading out into deeper water. Surface ocean mixed layers tend to be thicker during the winter due to the more vigorous vertical mixing action of breaking storm waves and wind-driven circulation.

What were S,T profiles around 2/6/12?

What would be predicted effect of surface duct on sonar and/or explosive-like sounds?

This (mostly news footage) video shows a few stills of Jesse Huggins (?) and others dissecting the right side of L-112. Contact these people seeking video or photos of the right side of her head and body before and during the initial necropsy…

Read More

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook