Case study: Fisheries on a slow path to sustainability

After working out what sustainability science is, and all of the different fields it incorporates, I chose to focus on the fishing industry and what attempts it is making to be on a sustainable path, after large declines in many fish stocks, as my case study example. I chose a paper by Daniel Pauly et al. called Towards Sustainability in World Fisheries (Nature, 2002). This article reviews the practices of the fishing industry in the past, what they have begun to do to achieve sustainability, and what is needed in the future to try to enforce sustainability practices.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the fishing industry began growing rapidly around the world. Within 10 to 15 years of this rapid growth, and increase in government encouragement to make more catches, public examples of fish stocks crashing began to surface. What I found shocking while reading this paper was that, even though there were clear examples of depletions in fish populations (ie. cod populations in eastern Canada), the fishing industry had already become so huge that there was always an acceptable excuse to let fishing continue in the same manner around the world. Often times declines were blamed on “unspecified environmental change”, and it was also recently discovered that the People’s Republic of China had been over-reporting their catches, changing the statistics of how much global fish stocks had been declining since approximately the 1980s.

Since fishing became a large global industry, there has been some sort of monitoring of the fish stocks, in some attempt to preserve sustainability. Single-species assessments were traditionally being used and more sophisticated versions are still in practice, but as Pauly et al. explained, there have been some flaws in this approach which have led this system to fail. The problems include underestimating the severity of stock declines, and the failure to put short-term management of the stocks in place. There are also other impacts that the fishing industry is having that have not fully been taken into account when putting sustainability management in place. Depletion of the target fish species is also having an impact on the rest of the ecosystem.  Food webs in the marine environment are being disrupted with the removal of species in the mid-trophic levels, and rather than focusing on single species, ecosystems as a whole should be considered when working on sustainability management. There is also an issue with “overcapitalization” of fisheries, partly due to allowing increase in fishing vessel size, governments paying subsidies to fishers, and different types of fisheries with different rules that are not being closely monitored.

As more of the issues with the fishing industry have come to light, there has been a bigger focus on aquaculture (ie. fish farms) which many believe could be the solution to depleted wild fish stocks, but Pauly et al. point out some potential issues with this solution aswell. I was surprised to learn that aquaculture operations are actually using a lot of natural resources, and even more surprised to learn that they are even using wild stock fish to operate. Some aquaculture operations fatten their carnivorous fish with fish meal, which is actually made out of ground up fish such as herring!

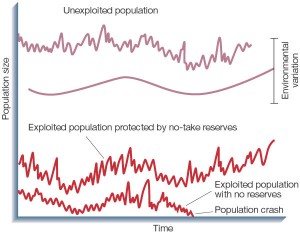

Unfortunately, it seems to me that the fishing industry is still headed towards an unsustainable and grim future after reading the majority of this paper, but Pauly et al. do provide some hope near the end. Though there is still a lot of work to be done from a management standpoint, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) that have a “no-take” policy have already shown to help increase depleted fish stocks that fuel the fishing industry. This is shown in the image below where Pauly et al. are comparing unexploited fish stocks with exploited stocks with and without no-take reserves. There are now fish scientists working feverishly around the world to gather data and plead their case for MPAs to be set up and well protected.

A maybe less likely goal is to begin downsizing and decomissioning some commericial fishing fleets so that there is simply less fishing occuring. Since the demand for fish is so high, this would be a hard plan to begin implementing, but it deserves serious consideration in the future if the fish stocks continue to decline.

This week my classmates and I were fortunate enough to get a glimpse into the world of fish research when we helped out a group studying the endangered chinook salmon population in the San Juan area. This fit in perfectly with my case study since the chinook stocks are very low, and they are also being hatched in hatcheries to try to improve the stocks (we managed to catch one hatchery fish, which are marked before they are released). The data being collected included a fin biopsy and preserving the stomach contents to analyze what the juveniles are eating. This is the type of biological research the makes a large contibution to sustainability science and gives hope to the future of global fish stocks.

This week my classmates and I were fortunate enough to get a glimpse into the world of fish research when we helped out a group studying the endangered chinook salmon population in the San Juan area. This fit in perfectly with my case study since the chinook stocks are very low, and they are also being hatched in hatcheries to try to improve the stocks (we managed to catch one hatchery fish, which are marked before they are released). The data being collected included a fin biopsy and preserving the stomach contents to analyze what the juveniles are eating. This is the type of biological research the makes a large contibution to sustainability science and gives hope to the future of global fish stocks.

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook