Once discussing sustainability science with the class and writing the previous blog about what sustainability science is I found a case study, which encompasses the sustainability of coral reefs and marine ecosystems.

People love to view the beautiful and rare ecosystems around the world, the mystery of a rainforest or the beauty of marine reefs. However, the constant tourism and destruction is destroying these rare ecosystems; but I’m focusing on the Abore Reef reserve in New Caledonia. Doyen et al. researched how over exploited marine ecosystems can be sustained by being transformed into a protected area (2007). In summary, reserves are very beneficial because they restore fisheries, ecosystems, and conserve biodiversity.

According to the National Research Council (NRC) and the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) the last 10 years spent developing ideas about sustainable science have been influenced more by political rather than scientific perceptions (1999). The economical benefits tend to cause complications for scientific purposes. However, marking a location a protected area shows a positive effect with results of increased fish size, abundances of spawning, and surrounding the reserve having increased spillover of recruited stages and larval dispersion (Doyen et al. 2007). The coral reef ecosystem is one where many organisms use the coral for shelter and sanctuary from predators so when the reef is negatively affected the whole ecosystem suffers.

Major constrains to marine ecosystems, such as coral reefs, are over exploitation and harsh weather, such as cyclones. Cyclones increase oscillations of coral and trophic densities in relation to the refuge effect. Increased cyclone frequencies cause concerns with organism interactions which could lead to trophic cascades. The effects of various cyclone frequencies are demonstrated in figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Time in this figure is for the next 30 years if there were no fishing efforts. The top graph (a) is if no cyclones occur, middle graph (b) a cyclone every 6 years, and the bottom graph (c) a cyclone every 4 years. The black line indicating piscivores, dark blue-carnivores, green-herbivores, light blue-small prey, red-coral state.

When looking at reefs under current cyclonic frequencies (1 cyclone every 6 years) with 20% harvesting efforts and a reef that is not protected results are similar showing carnivores and herbivores will flat line.  However, with a protected coral reef there is a much higher recovery rate because the biodiversity is significantly better. If the cyclone frequency was to increase (1 cyclone every 4 years) with 20% harvesting efforts and a coral reef is not protected carnivores and herbivores would be over exploited leading to a significant decrease in recovery rate due to a drop in biodiversity. If a coral reef is under protection the biodiversity would be good and the ecosystem would have a higher recovery rate.

After discussing case studies the class took a trip to Lopez Island to assist with some research being conducted on juvenile Chinook salmon.  Beam Reach students along with local volunteers congregated to assist in bringing in the net once it was filled with fish. We collected sand lance, juvenile Chinook, and herring. The Chinook were sedated and then underwent a process called a lavage. Measurements of individual fish were taken, stomach contents preserved, quantity of each species noted, and tail clips for future fin biopsies. This picture shows the group of us picking out the desired fish from the second haul (3 hauls are allowed in one day’s efforts). The continued research conducted on Lopez Island and surrounding areas helps to sustain the endangered Chinook salmon population along with the organisms below (sand lance) and above (killer whales) in the food chain.

Beam Reach students along with local volunteers congregated to assist in bringing in the net once it was filled with fish. We collected sand lance, juvenile Chinook, and herring. The Chinook were sedated and then underwent a process called a lavage. Measurements of individual fish were taken, stomach contents preserved, quantity of each species noted, and tail clips for future fin biopsies. This picture shows the group of us picking out the desired fish from the second haul (3 hauls are allowed in one day’s efforts). The continued research conducted on Lopez Island and surrounding areas helps to sustain the endangered Chinook salmon population along with the organisms below (sand lance) and above (killer whales) in the food chain.

The data in the case study and ongoing research on Lopez clearly demonstrate how key sustainability science is to preserving life in various ecosystems. It is not only about one organism or species, but the pressures people put on ecosystems as well as how different organisms interact with one another. Between the case study and research on Lopez people are discovering new information that brings us that much closer to understanding the various levels of the food chain and the ecosystem (shown in the picture to the left).

The data in the case study and ongoing research on Lopez clearly demonstrate how key sustainability science is to preserving life in various ecosystems. It is not only about one organism or species, but the pressures people put on ecosystems as well as how different organisms interact with one another. Between the case study and research on Lopez people are discovering new information that brings us that much closer to understanding the various levels of the food chain and the ecosystem (shown in the picture to the left).

Read More

After working out what sustainability science is, and all of the different fields it incorporates, I chose to focus on the fishing industry and what attempts it is making to be on a sustainable path, after large declines in many fish stocks, as my case study example. I chose a paper by Daniel Pauly et al. called Towards Sustainability in World Fisheries (Nature, 2002). This article reviews the practices of the fishing industry in the past, what they have begun to do to achieve sustainability, and what is needed in the future to try to enforce sustainability practices.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the fishing industry began growing rapidly around the world. Within 10 to 15 years of this rapid growth, and increase in government encouragement to make more catches, public examples of fish stocks crashing began to surface. What I found shocking while reading this paper was that, even though there were clear examples of depletions in fish populations (ie. cod populations in eastern Canada), the fishing industry had already become so huge that there was always an acceptable excuse to let fishing continue in the same manner around the world. Often times declines were blamed on “unspecified environmental change”, and it was also recently discovered that the People’s Republic of China had been over-reporting their catches, changing the statistics of how much global fish stocks had been declining since approximately the 1980s.

Since fishing became a large global industry, there has been some sort of monitoring of the fish stocks, in some attempt to preserve sustainability. Single-species assessments were traditionally being used and more sophisticated versions are still in practice, but as Pauly et al. explained, there have been some flaws in this approach which have led this system to fail. The problems include underestimating the severity of stock declines, and the failure to put short-term management of the stocks in place. There are also other impacts that the fishing industry is having that have not fully been taken into account when putting sustainability management in place. Depletion of the target fish species is also having an impact on the rest of the ecosystem.  Food webs in the marine environment are being disrupted with the removal of species in the mid-trophic levels, and rather than focusing on single species, ecosystems as a whole should be considered when working on sustainability management. There is also an issue with “overcapitalization” of fisheries, partly due to allowing increase in fishing vessel size, governments paying subsidies to fishers, and different types of fisheries with different rules that are not being closely monitored.

As more of the issues with the fishing industry have come to light, there has been a bigger focus on aquaculture (ie. fish farms) which many believe could be the solution to depleted wild fish stocks, but Pauly et al. point out some potential issues with this solution aswell. I was surprised to learn that aquaculture operations are actually using a lot of natural resources, and even more surprised to learn that they are even using wild stock fish to operate. Some aquaculture operations fatten their carnivorous fish with fish meal, which is actually made out of ground up fish such as herring!

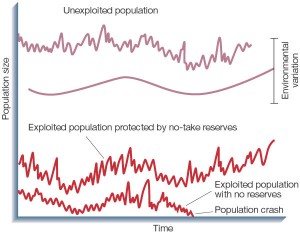

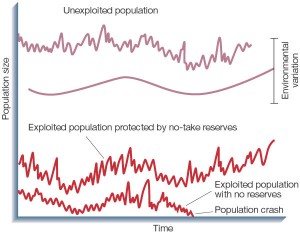

Unfortunately, it seems to me that the fishing industry is still headed towards an unsustainable and grim future after reading the majority of this paper, but Pauly et al. do provide some hope near the end. Though there is still a lot of work to be done from a management standpoint, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) that have a “no-take” policy have already shown to help increase depleted fish stocks that fuel the fishing industry. This is shown in the image below where Pauly et al. are comparing unexploited fish stocks with exploited stocks with and without no-take reserves. There are now fish scientists working feverishly around the world to gather data and plead their case for MPAs to be set up and well protected.

A maybe less likely goal is to begin downsizing and decomissioning some commericial fishing fleets so that there is simply less fishing occuring. Since the demand for fish is so high, this would be a hard plan to begin implementing, but it deserves serious consideration in the future if the fish stocks continue to decline.

This week my classmates and I were fortunate enough to get a glimpse into the world of fish research when we helped out a group studying the endangered chinook salmon population in the San Juan area. This fit in perfectly with my case study since the chinook stocks are very low, and they are also being hatched in hatcheries to try to improve the stocks (we managed to catch one hatchery fish, which are marked before they are released). The data being collected included a fin biopsy and preserving the stomach contents to analyze what the juveniles are eating. This is the type of biological research the makes a large contibution to sustainability science and gives hope to the future of global fish stocks.

This week my classmates and I were fortunate enough to get a glimpse into the world of fish research when we helped out a group studying the endangered chinook salmon population in the San Juan area. This fit in perfectly with my case study since the chinook stocks are very low, and they are also being hatched in hatcheries to try to improve the stocks (we managed to catch one hatchery fish, which are marked before they are released). The data being collected included a fin biopsy and preserving the stomach contents to analyze what the juveniles are eating. This is the type of biological research the makes a large contibution to sustainability science and gives hope to the future of global fish stocks.

Read More

What exactly is sustainability science, and why is it important? According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), sustainability is societies ability to meet its current needs in addition to protecting the ability of subsequent generations to meet their own needs. Individuals in society seem to understand the importance of securing resources not only to satisfy their current needs, but also the future needs of their descendants. As individuals and family units, the value of sustainability is immeasurable. Parents and grandparents alike safeguard resources needed to provide adequate care to meet the demands of their offspring. As a society however, we often ignore the impact that our decisions have on those immediately around us, as well as worldwide. This encompasses not only the impact societies decisions have on the human population, but all creatures that share the earths resources with us.

Science is defined as systematic knowledge of the physical or material world gained through observation and experimentation. Throughout the last few decades it has become increasingly evident that in order for society to maintain the luxuries and lifestyles it has grown accustomed to, it must defend the environment in which it occupies. Through exploiting minerals, plants, water sources, and animals; we often destroy our most precious and valuable resources. As we continue to gain knowledge about the world around us, it is palpable that sustainability is a science. Sustainability science requires discipline, and understanding about an ever-changing world and all of it’s components.  Through understanding, defending, and caring for the resources we often take for granted, we protect the ability of subsequent generations to meet their own needs.  It is obvious that sustainability science is essential to ensuring the survival and success of all populations.

If we do not practice sustainability science now, where will we be in the future?

Read More

On the first day of Sustainability Science class, we were asked what exactly sustainability science was. I confidently wrote down in my notebook: “A way to conduct scientific studies that involves little or no disturbance to the surrounding fauna and flora while effectively collecting data usable for quantifiable research.†I pretty much thought that sustainable science was a way of collecting data without disturbing, polluting, or impacting the natural surrounding wildlife. And since we’re using a sailing catamaran, the Gato Verde, that runs on biodiesal and can generate its own power, further confirmed in my mind my definition of sustainability science. After saying this out loud, every other person in the room (including the professors) defined sustainability science through the problems being addressed, such as energy crisis, toxic atmospheres and oceans, and high CO2 levels, and finding a way to combine the sciences into one (sustainability science) to solve these problems. It is the knowledge that ultimately moves toward a place where humans and the environment can coexist comfortably.

Right now I think that’s the obvious definition. But at the time I was thinking about my Deep Sea Conservation class that I had taken at Eckerd College the previous winter term. I distinctly remember an article that my professor had us read, and it was about observing deep-sea fauna next to hydrothermal vents. They noticed that the deep-sea shrimp being observed by the vents with bright lights were actually blinded by the intensity of the lights, and the shrimp by the vents that weren’t exposed to the light showed no signs of disturbance. Physical harm resulted from scientific inquiry. The same goes for trawling in the oceans. Trawling is corrosive and can be detrimental for long periods of time following the trawl. The amount of knowledge obtained by such practices can be seen positively, but such a destructive way to go about research has one wondering whether or not we as scientists are helping or contributing to the problem.

Fig. 1. The semi-invasive of a stomach lavage done on a juvenile Chinook Salmon on Lopez Island, August 27th, 2011.

On the 27th of August, we “Beamers†and Robin just went to Lopez Island to go fishing, and I honestly didn’t know what to expect. Were we catching and releasing? Were we going to just see what we caught and chart the amounts of each species we saw? Were we catching dinner? It turned out that we were actually going to observe the capture of juvenile Chinook salmon. Salmon here is considered a keystone species, meaning that it plays a major role in the entire ecosystem. Here, it’s a major prey item to a wide diversity of creatures, which includes orcas, bears, pinnipeds, and large birds of prey. And hey, people find them tasty as well. With these salmon they performed a stomach lavage, which is pretty much flushing the stomach of its content to see what they prefer to eat.

With Chinook holding an endangered species status, they had to take every precaution to avoid fatalities with the fish. At .5% mortality, I’d say that they’re doing quite well. This practice is considered to be “semi-invasive,†one that I personally believe is worth investigating if it means that we’ll have hard evidence of what is causing these very important fish to struggle as a species, and what would need to be done to help it make a come-back.

Looking at the different definitions of sustainability science that occurred, I must say that perhaps they are all accountable. It is a science that moves us forward to a sustainable planet, and it’s also a science that should be as non-invasive as possible. Analyzing the wide spectrum of invasive practices, as a young scientist, I realize that there is a fine line between conducting strictly non-invasive research, and doing so much research that scientists themselves have an impact on the ecosystems of the planet. It’s a very opinionated topic, and a scientist in these environmentally stressful times must justify how much they’re willing to impact the environment being studied in order to gain the proper amount of knowledge to contribute to a sustainable world.

Read More

Have you ever had to define a word you use everyday and struggle to give a simple explanation? The Fall 2011 Beam Reach class was asked to simply define sustainability science prior to the first lecture of sustainability science. We all looked with blank stares as we collectively appeared to be at a loss of words. However, it was a bit comforting knowing participating professors were struggling just as much as the students.

So what is sustainability science? My definition was the study of how to maintain/ sustain populations and its ecosystem. After pooling various definitions we confidently said there is no specific definition of sustainability science. Some said the definition had to do with how research was carried out, others what yours studying, yet further more how it effects the ecosystems. Sustainability science is such a broad category and encompasses many things that we cannot pin point a specific explanation.

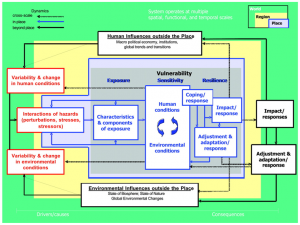

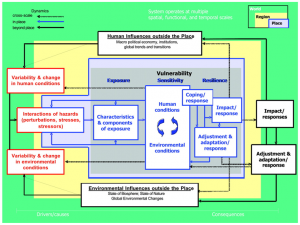

According to Clark et al. the questions we need to ask ourselves when looking at sustainability science are: What is to be sustained? For how long? What is to be developed? (2005). Clark and Dickson state sustainability science is taking science and technology and focusing on interactions between nature and society (2003). However, it also encompasses seeing how social alternations shape the environment and how the environment alters society. Knowing these two factors effect each other Turner et al. diagrammed (below) how various elements are dependent on one another (2003). The study of sustainability science is not studying one element but how many outside factors can influence each other. If we are careless our actions can alter ecosystems in ways that make it impossible to recover.

After talking about sustainability science I started thinking more about the definition and how much of an impact these factors have on one another. Since the words sustainability science are so hard to describe, because it umbrellas an extremely wide range of studies, everyone has a different explanation. After further discussion and reading, to me, sustainability science meas using research and technology to study how ecosystems and populations effect each other while focusing on how to sustain/ maintain them using the least invasive methods as possible. If someone comes up to you and asks what is sustainability science can you define it?

Later on in during this program the Fall 2011 class will be doing a sustainability project to help the various ecosystems and organisms here on and around the San Juan Islands (ie. Southern Residents). We have not completely decided on our project yet, however, I’m sure more will be posted when the time comes.

Read More

On our first day of Beam Reach fall 2011 sustainability science class, we were asked what seemed to be a rather simple question: “What is the definition of sustainability science?”. When we went to put our pens to paper we quickly discovered that this seemingly simple question really had no simple answer. My initial definition was “Using scientific research and methods to improve the sustainability of natural resources”. My classmates had varying degrees of similar answers, but it led to the question: what is sustainability science REALLY?

The very simple definition that Val gave us seemed to lead us on the right track: “A quest for basic knowledge that could be used in a very practical way”. It is the science that starts at the very basics of how ecosystems work, and then links many different parts of our world. It involves finding a balance between meeting human needs and preserving the natural way that the ecosystems providing for us work. There is a huge overlap of different fields that contribute to creating sustainability science, as depicted by the National Academy of Sciences in the book Our Common Journey: A Transition Towards Sustainability (1999):

This diagram shows how four areas of research all contribute to the sustainability science field. First, biological science research is used in order to understand  the natural systems in which we are utilising and affecting. Technological systems research is used to determine the technological advancements that can be made to move towards a goal of sustainability. Geophysical systems research is used to determine how we are affecting the earth in terms of climate and geography, which in turn could potentially affect the biological systems in which we are utilising. Finally, social systems research is used to assess society’s values and points of view towards human impact on the earth’s systems.

After putting some more thought into the idea of sustainability science, I realized how big of a challenge is it for us as a society to move towards a sustainable way of life. It not only involves different aspects of science, but it also involves political and social aspects, and it is inevitable that the parties involved will have disagreements on the best approach given their differences in point of view.

Sustainability science is a rather simple term that is becoming ever more commonly used in today’s society, but don’t be fooled, it is deceivingly complicated, but will be well worth the effort in the future if we are able to stay on a path to a sustainable way of life, where we have less impact on the earth and are able to find the balance between our needs and preserving natural systems for generations to come.

Read More

During the spring 2011 program Carlos Javier Sanchez chose to make Beam Reach a focal point of his final project as a Master of Communication in Digital Media at the University of Washington (UW). Carlos spent many weeks documenting our 10-week program — both on land at the UW Friday Harbor Labs and at sea on our sailing research vessel, the Gato Verde.

Embedded below are the fruits of his labor — a highlight video and some shorts. We look forward to continuing to work with Carlos as a Digital Content Producer and thank him here for all of the amazing footage, still imagery, and in-air recordings he captured for us.

Beam Reach overview video

Beam Reach is an off-campus adventure that lets advanced undergrads and recent graduates live the life a marine biologist. It’s a 10-week taste of what it’s like to be a graduate student or a professional field scientist.

The cold plunge off the Friday Harbor Labs dock

Beam Reach Cold Plunge 2011 from Carlos Javier Sanchez on Vimeo.

Knotcraft: the sheetbend, bowline, and clove hitch

Gato Verde Adventure Sailing captain, Todd Shuster, teaches Beam Reach Students how to get knotty.

Beam Reach is an off-campus adventure that lets advanced undergrads and recent graduates live the life a marine biologist. It’s a 10-week taste of what it’s like to be a graduate student or a professional field scientist.

Captain Todd Shuster has been involved in sailing education for over 20 years. Todd is a US Coast Guard licensed Captain, a USSAILING instructor and instructor trainer. He has taught wilderness sailing courses in Baja, Mexico for The National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), and has run several sailing programs for universities, yacht clubs, and summer camps.

Learning to sail a 42′ catamaran

Gato Verde’s captain, Todd Shuster, teaches Beam Reach students how to sail on the Salish Sea.

How to get up to the modern-day crow’s nest

Mandy Bailey rises above the rest.

Read More

This looks like a fun (and free!?) opportunity for Beam Reach alumni or prospective students to a week of field research experience in Scotland this fall. There’s only 10 days before the application deadline, so hurry if want to learn about cetacean (mainly bottlenose dolphin) census, behavioral observation, marine mammal rescue techniques.

Read More

Beam Reach students along with local volunteers congregated to assist in bringing in the net once it was filled with fish. We collected sand lance, juvenile Chinook, and herring. The Chinook were sedated and then underwent a process called a lavage. Measurements of individual fish were taken, stomach contents preserved, quantity of each species noted, and tail clips for future fin biopsies. This picture shows the group of us picking out the desired fish from the second haul (3 hauls are allowed in one day’s efforts). The continued research conducted on Lopez Island and surrounding areas helps to sustain the endangered Chinook salmon population along with the organisms below (sand lance) and above (killer whales) in the food chain.

Beam Reach students along with local volunteers congregated to assist in bringing in the net once it was filled with fish. We collected sand lance, juvenile Chinook, and herring. The Chinook were sedated and then underwent a process called a lavage. Measurements of individual fish were taken, stomach contents preserved, quantity of each species noted, and tail clips for future fin biopsies. This picture shows the group of us picking out the desired fish from the second haul (3 hauls are allowed in one day’s efforts). The continued research conducted on Lopez Island and surrounding areas helps to sustain the endangered Chinook salmon population along with the organisms below (sand lance) and above (killer whales) in the food chain. The data in the case study and ongoing research on Lopez clearly demonstrate how key sustainability science is to preserving life in various ecosystems. It is not only about one organism or species, but the pressures people put on ecosystems as well as how different organisms interact with one another. Between the case study and research on Lopez people are discovering new information that brings us that much closer to understanding the various levels of the food chain and the ecosystem (shown in the picture to the left).

The data in the case study and ongoing research on Lopez clearly demonstrate how key sustainability science is to preserving life in various ecosystems. It is not only about one organism or species, but the pressures people put on ecosystems as well as how different organisms interact with one another. Between the case study and research on Lopez people are discovering new information that brings us that much closer to understanding the various levels of the food chain and the ecosystem (shown in the picture to the left).

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook