Beaked whales respond to mid-frequency sonar test

Brandon Southall gave a great synopsis today of an impressive study (SOCAL-10) of how cetaceans respond to simulated sounds, including mid-frequency sonar. (Edit 1/20/11: recorded lecture is at http://www.ustream.tv/recorded/11956611 ) Responses were assessed using data from a suite of instruments, including passive acoustic monitoring and tags attached to the animal that reported position at the surfaces, as well as underwater depth, heading, and received sound level.

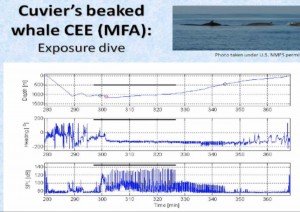

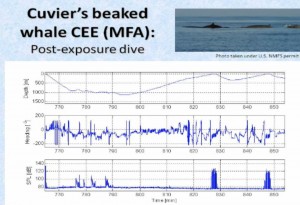

The highlight from my perspective was that different cetaceans off the coast of southern California seem to respond differently to the simulated sounds.   While a sperm whale showed no mid-dive response to simulated mid-frequency sonar (210 dB 15-element vertical source rather than the military’s 235 dB 30-element source), a beaked whale showed a strong response mid-dive — it suddenly switched from swimming around in different directions to swimming faster (more flow noise) on a steady heading (see screen-grabs below).

Southall commented during his talk that “Beaked whales, like harbor porpoises, seem to be particularly sensitive.” In the interesting back story provided by the Smithsonian, Southall similarly noted that in the Bahamas “beaked whales seemed much more responsive than other species, like pilot whales.”

An outstanding question posed by Brandon today as he presented the slides shown below is whether or not the beaked whale was swimming away from the SOCAL sonar source or not. In these Matlab plots, the exposure is denoted by the black bar. I think the red circle represents the time when the sonar sounds were first emitted (at full source level?).

A dive during which whale was exposed to simulated sonar and responded with increased flow noise and steady heading

It seems an answer could be derived by estimating the beaked whale’s speed from the flow noise time series and then combining it with the heading data to estimate the whale’s track underwater. If the location of the whale when it dove is known (even roughly) relative to the sound source, then it may become clear whether the whale headed away from the source or not. From about the onset of the exposure for about an hour the animal was headed between -90 and -180 degrees.

Assuming a heading of 0 degrees represents magnetic or true north, the bulk of the response movement was to the southwest. The descent included some slow turns throughout the compass points, but was also predominantly to the southwest or northwest with the highest speed sections (based on the flow noise increasing with speed) occurring when the animal was headed generally southwest. So, if the source was east (or maybe north) of the dive location, then the response was probably away from the source. If the source was west or south of the dive location, then the response may have been toward the source…

Also, in the question session within the uStream chat window, a user named strandednomore posed a provocative question which went un-answered:

We would like to know why nothing was mentioned about 7 stranded/ship strike cetaceans that was found in California in September? Strandings included 5 endangered blue whales, one pilot whale and one juvenile humpback. Prior to SOCAL-10 and Navy tests in San Diego nearly no cetaceans stranded in California from January up to August, then suddently we had 7!

Overall, this was a great use of streaming video. Thanks to Orca Network for the Facebook reminder to tune in and a suggested improvements for the Smithsonian folks: clarify how virtual audience members should submit questions; respond to audience comments in the ustream chat window; provide a link to the archived recording immediately after the broadcast ends.

Read More

Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook